1Student, EPGDIB (Summer), 2023-25, IIFT Delhi

2Department of Economics, Indian Institute of Foreign Trade (IIFT), Delhi, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This article examines the transition of global sourcing hubs from China to India, driven by economic, political and social factors. A mixed methods approach using trade data and existing literature including relevant policies of the Government of India is employed for the purpose of analysis in this study. As per the findings of this work, the key drivers of this shift are India’s competitive labour costs due to an abundant labour force, favourable government policies and improving infrastructural facilities. The study concludes that while challenges on the fronts of customs, infrastructure, international shipments, logistical quality and competence, tracking and tracing and timeliness remain, India is poised to become a major player when it comes to global sourcing. These insights are crucial for businesses and policymakers aiming to navigate the evolving landscape of global trade sourcing. In sum, challenges and opportunities linked with India’s infrastructure and scalability for trade and logistics are crucial in determining its global role. As India strives to compete with China in becoming the next global sourcing hub, the importance of robust logistics and shipping networks cannot be ignored.

China, global sourcing, India, logistical quality

Introduction

Over the past decade, China has experienced remarkable economic growth, solidifying its position as a global economic powerhouse. This period has been characterised by significant advancements in various sectors, driven by strategic policies and robust economic planning (Atkinson & Atkinson, 2024; Shah et al., 2024).

China’s industrial sector is the main contributor to its economic growth. The country is often called the Factory of the World as it has invested heavily in Innovation and Technology, leading to advancements in manufacturing, Artificial Intelligence and green energy. These investments have not only pushed productivity but also positioned China as a leader in high-tech industries. Many multinational companies (MNCs) rely on Chinese factories to manufacture goods, from electronics and textiles to machinery and automobiles (Atkinson & Atkinson, 2024; Deutch, 2018; Spoggi, 2020).

China’s favourable government policies play a crucial role in attracting investors and getting foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows. They also incentivise businesses to expand their operations in the country promoting its overall development. The humongous labour force and extensive supplier ecosystem support the manufacturing sector, helping drive productivity, expertise and cost-effectiveness (Atkinson & Atkinson, 2024; Deutch, 2018). China’s investment in its physical infrastructure in the form of highways, railways and ports provides a boost to its domestic and trade development and builds its reputation, domestically as well as internationally (Atkinson & Atkinson, 2024; Deutch, 2018).

However, recently, due to the pandemic and the growing economic tensions between the US and China, many businesses are reconsidering their reliance on Chinese suppliers and diversifying their supply chains. This has given rise to China-plus-one strategy. As a result, there is growing interest in finding alternative sourcing options with India emerging as a potential replacement for China (Lazard, 2024).

The primary objective of this article is to assess India’s potential as an alternative to China for global sourcing driven by socio-economic and political factors. Past literature has mainly focused on the competitiveness of other developed economies. While some studies touch upon India’s potential; none systematically compares the country’s viability as a sourcing alternative to China.

This article is divided into the following sections. First, an introduction to the research topic is given. Second, a thematic review of literature is conducted, centred around the PESTEL (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal) framework. Third, the methodology of this study is explained. Last, conclusion and future policy implications of this work are explicated.

The next section reviews existing literature within a PESTEL framework.

Review of Literature

According to Balu et al. (2022), global sourcing can only be applied to highly standardised parts and components in manufacturing.

Innovations in global supply chains have emerged as critical contributors to flexibility and competitive strength, ultimately leading to beneficial impacts for the firm, industry, and nation (Dolgui & Ivanova, 2017). China is at the forefront of adopting automation and robotics in its manufacturing processes. From advanced robotic assembly lines to automated warehouses, these technologies infuse efficiency, precision and productivity in the supply chains (Zhao, 2023).

Recently, India’s rise as a viable global sourcing alternative to China has attracted considerable interest. This transition is driven by several factors which could include better competitive pricing, a youthful and skilled labour force and a benign business climate for foreign investors. Moreover, India’s unique path to integration with the global markets, characterised by limited FDI yet, significant growth in textile and apparel exports, highlights the importance of domestic policy changes and evolving demand structures being the key factors in the country’s emergence as competitive sourcing hub (Madhani, 2008).

Evolving Global Dynamics

The global landscape has undergone significant transformations over the past few years. The collapse of the Soviet Union led to the rise of the United States as the sole superpower, but China’s recent ascent is moving the world towards multi-polarity. Its economic prowess, technological advancements and global influence have positioned it as a major force (Brooks & Wohlforth, 2015).

Simultaneously, Southeast Asia has also witnessed remarkable growth, with countries like Singapore and Vietnam becoming key players in the global economy. India too, has emerged as a prominent player, driven by its expanding economy, large population and diplomatic initiatives (HSBC, 2024).

The ongoing Ukraine-Russia conflict highlights the geopolitical complexities of the modern world. In response to these dynamics, many MNCs are adopting a China-plus-One strategy, diversifying their supply chains to reduce reliance on any single country. This strategy has placed India in the spotlight as an attractive alternative sourcing destination. India’s competitive labour costs, skilled workforce and improving business environment make it a compelling choice for companies seeking to diversify their sourcing strategies (Lazard, 2024).

Labour Cost Analysis: China Versus India

Steep Increase in China’s Manufacturing Costs

China’s decades-long reign as the ‘world’s factory’ is facing headwinds due to escalating manufacturing costs, raising challenges for businesses in that country and altering the global manufacturing landscape. Several factors contribute to these rising costs. Significant wage growth for Chinese workers over the past decade is one. Another is a shrinking labour pool due to an ageing population and declining birth rates. Additionally, increasing cost of raw materials and other inputs is also driving up manufacturing costs (Atkinson & Atkinson, 2024; Lazard, 2024).

The rise in manufacturing costs in China has had various implications for businesses. Some firms have relocated their operations to countries with lower labour costs, notably, those in Southeast Asia. Others have invested in automation and advanced technologies to boost productivity and reduce dependence on manual labour. Some have passed higher costs to customers through increased prices. The Chinese government is aware of the challenges posed by rising manufacturing costs and is taking steps to address them. These measures include policies to promote technological innovations, skill development and economic restructuring (Global Data, 2024; Lazard, 2024).

The future of manufacturing in China remains uncertain. However, it is evident that the country’s low-cost advantage is no longer as strong as it once was. Businesses operating in China will need to adapt to the changing landscape to stay competitive.

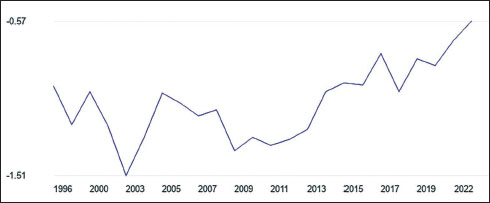

The issue of rising labour costs in China is complex and multifaceted, with both positive and negative implications. Labour costs have increased for the period 2010–2021 (Figure 1).

Some of the key reasons for rising labour costs in China are first, wage growth and improved standard of living. One of the primary causes of increasing labour costs in China is the significant wage growth experienced by workers over the past decade. Higher wages contribute to an improved standard of living for Chinese workers, allowing them to afford better housing, healthcare, education and consumer goods. Second, shrinking labour pool. China’s labour force is gradually shrinking due to factors such as an ageing population, declining birth rates and urbanisation. As the supply of available workers decreases, employers are compelled to offer higher wages to attract and retain talent. This scarcity of labour has played a major role in driving up labour costs. Third, increased regulatory burden. China has implemented stricter environmental regulations and labour laws in recent years. While helpful for sustainability and worker well-being, these measures often translate into higher compliance costs for manufacturers. Fourth, land and energy costs. Rapid industrialisation has led to increased competition for land and resources, driving up their prices. Manufacturing hubs, particularly in coastal areas, face soaring land costs, impacting factory operations. Similarly, energy prices have risen, adding to overall production expenses. All in all, higher labour costs in China can pose challenges for businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that rely heavily on low-cost manufacturing. Some companies may struggle to maintain profitability and could consider diversifying their supply chains or moving operations to countries with lower labour costs (Global Data, 2024; Yang et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2023).

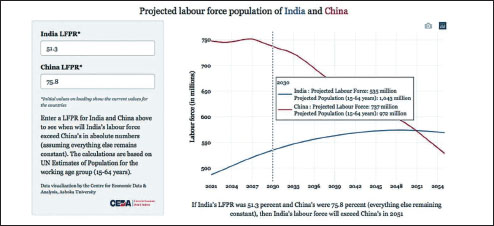

India’s Competitive Edge: Cheap and Abundant Labour

India’s supply of inexpensive labour has long been a key attraction for global businesses. The same is on account of the country’s huge population, mainly consisting of young people with diverse skill sets. This demographic dividend results in a vast workforce available at low labour costs as compared to other countries. Furthermore, India’s labour market is characterised by a mix of low and semi-skilled workers and highly educated professionals. With a growing focus on education, the country is blessed with a skilled workforce in various fields such as technology, engineering and services. The sheer variety offered by a differently skilled workforce allows businesses to choose labour that best fits their specific needs and budget constraints. An accessible and affordable labour force has encouraged many MNCs to outsource some of their business operations to India. However, while India’s labour remains cost-effective, it is important to consider other factors such as infrastructure, logistics, regulatory environment and market access when making investment decisions in the complex global business landscape. Some of these could be elaborated as follows. First, demographic advantage is offered by a large and expanding population, with a notable portion of its workforce being young and relatively low-skilled. This demographic benefit results in a vast pool of labour. Second, wage disparity is another area of concern. There are significant wage differentials between urban and rural areas in India, as well as across regions. Labour costs are generally lower in rural areas where the cost of living is lower. This wage disparity makes it appealing for businesses to utilise relatively inexpensive labour available in rural parts of the country. Third, the Government of India (GOI) has introduced several initiatives and reforms to boost labour-intensive sectors and draw foreign investments. Programmes such as Make in India are designed to strengthen the manufacturing sector and create job opportunities in the same. These efforts, along with supportive policies and tax incentives, help ensure the availability of affordable labour in the country (IBEF, 2024a; Raman, 2016) (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

PESTEL Analysis

PESTEL analysis studies the macroeconomic framework external to the firm (s) (Buye, 2021; Christodoulou & Cullinane, 2019; Debourdeau et al., 2021). It is a diagnostic tool for strategic business planning that provides a tactical framework for understanding the exterior influences on a business entity. It is used by firms for evaluation of the impact that the outside environment might have on a project. It groups external factors into various classifications under the broad headings of PESTEL considerations. It is one of the most sought-after tools of investigation used in strategic management (Christodoulou & Cullinane, 2019).

Political Analysis for India

India, recognised as a secular democratic republic, has exhibited significant political stability, especially in recent years. Political stability is one of the cornerstones of economic strength. The present administration is supportive of its industrial growth and aspires to elevate its exports to USD 2 trillion, exceeding half of the current GDP of USD 3.5 trillion. A range of initiatives, such as Make in India and Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes have been launched so as to enhance the production and export capabilities of domestic manufacturing firms. As a result of political stability, trade and investment policies are also favourable, with the GOI allowing up to 100% FDI in several industries.

Figure 1. Labor Cost Index of China (2010–2021, Base Year 2010 = 100).

Source: Global Data (2024).

Import tariffs and export incentives are periodically reviewed to align with both current trends and future goals. Ease of Doing Business is another important indicator and India has been improving its position over the years, thanks to a stable political and regulatory environment. As indicated in Figure 4, India’s political stability has grown over the last decade though it is still below the global average of -0.07 (IBEF, 2024b; Mitra, 2017).

Economic Analysis for India

The economy is another important component of PESTEL analysis. It is even more important given that India is one of the largest economies in the world in terms of nominal GDP. In line with this, it is one of India’s foremost ambitions to promote itself as a global manufacturing and export hub.

The country also stands out as the most promising economy among developing nations with bright future prospects. With a growing labour force and rising per capita incomes, the Indian economy is set to expand over the next 30 to 50 years. This creates a compelling reason for industries to establish factories in India, furthering both domestic and export markets. A number of schemes have been introduced in this regard. First, the PLI Scheme. This scheme provides financial incentives to companies that invest in manufacturing in India. The PLI scheme has been particularly successful in the electronics sector, where it has helped attract major global companies such as Apple and Samsung. Second, the Export Promotion Councils (EPCs) are government bodies that provide support to exporters in a variety of sectors. The EPCs offer a range of services, such as market research, training and export finance. Third, the Export-Import Bank of India (EXIM Bank) provides financial assistance to exporters, such as loans and guarantees. EXIM Bank also offers export insurance, which can protect exporters from the risk of non-payment. These are just some of the initiatives that the GOI is taking to boost exports. With these initiatives in place, India is well-positioned to achieve its goal of becoming a USD 1 trillion export economy by 2030 (Varghese, 2018; World Bank, 2024a).

Social Analysis for India

Social context is another complex and diverse component of PESTEL analysis. India’s societal environment is multifaceted and varied (with several religious, caste and ethnic groups) but it has some key characteristics that could help to augment its economic conditions. First, a large and expanding middle class, which is expected to reach 500 million by 2025. This social group is vital in so far it has increasing disposable incomes to spend on goods and services, giving a boost to the national GDP. Second, a young and educated workforce is an asset as the export sector is adaptable to new technologies and processes and proficient in English, the language of international trade. Third, a younger population compared to China, with a median age of 28, compared to China’s 39. India has a larger proportion of its population in the working-age bracket (15–64 years old). These bode well for the nation’s economic prosperity. As evident in Figure 2 and Figure 3, in terms of literacy and labour force participation, India lags behind China on several key social parameters (Chandrasekhar et al., 2006; Ministry of External Affairs, GOI, 2021; Singh & Paliwal, 2015).

Technological Analysis for India

India’s technological landscape is evolving rapidly with an emphasis on innovation and entrepreneurship. This innovative spirit is boosted by the presence of several top-tier universities and research institutions in the country. It serves as a significant centre for IT and software development. India has established itself as a global technology centre, drawing substantial investments from major tech companies such as Amazon, Apple, Meta and Google. The nation is well known for its strong IT services industry which plays a crucial role in its economic growth (Jain & Roy, 2024).

Figure 2. Human Capital.

Source: Foreign Policy (2023).

Figure 3. Projected Labour Force Population of India and China.

Source: International Economic Association (2024).

Figure 4. Political Stability Index for India (-2.5 Weak; 2.5 Strong).

Source: The Global Economy.com (2024).

There are numerous advantages of having a strong IT and ITES infrastructure. First, IT and software development is one of India’s key fortes. The country is already a key player in this domain and the sector is expected to develop further. India could enhance its expertise in cloud computing, artificial intelligence and machine learning. Second, electronics manufacturing is another area requiring attention from the policymakers. The country’s electronics manufacturing industry is on the rise and is anticipated to attract greater investments. The focus is on enhancing capabilities in consumer electronics, telecommunications equipment and medical devices sectors.

Third, life science is another domain where India has a robust presence. The same is projected to grow with time. The country is already concentrating on building expertise in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and medical devices (Jain & Roy, 2024; Jena, 2024).

Environmental Analysis for India

Apart from political, economic, social and technological analyses, a thorough environmental exploration is essential. There is a need to understand the significant interplay between a nation’s growth and the broader ecological factors influencing its path. The PESTEL approach, which includes PESTEL dimensions, provides a structured method of uncovering the various forces impacting India’s development. India is leveraging environmentally friendly policies to boost its exports in several ways. First, investing in renewable energy. As a leading investor in renewable energy, India is positively impacting its exports of solar panels, wind turbines and other renewable energy equipment. Second, promoting energy efficiency. By enhancing energy efficiency in the manufacturing sector, India is trying to reduce its pollution and make its products globally competitive. Third, developing environmental technologies. India is creating various eco-friendly technologies, such as pollution control equipment and water treatment systems, which are in high demand internationally and are helpful for boosting its exports (Manigandan et al., 2024).

India is often viewed as having superior ecological policies compared to China. While China has struggled with slow regulatory implementation, India is recognised for its more progressive environmental policies and a government dedicated to reducing pollution and promoting sustainable development as a policy objective. Nonetheless, India’s environmental policies still require improvement. The government must strengthen the enforcement of environmental regulations and invest more in conservational infrastructure. By continuing to improve these policies, India can position itself as a leading consumer, producer and exporter of environmental goods and services. Some of these ecologically friendly policies could be discussed here. The National Solar Mission has fostered a dynamic market for solar panels and other renewable energy equipment. In 2020, India’s solar exports reached USD 2.5 Billion. The Energy Efficiency Labelling Programme has reduced energy consumption in the manufacturing sector, making domestic products more globally competitive and creating new export opportunities for energy-efficient products. The Development of Environmental Technologies (DET) Programme is advancing new technologies like pollution control equipment and water treatment systems, which are in high demand internationally and are enhancing India’s production and export capabilities (Quitzow, 2015).

Legal Analysis for India

India is blessed with a robust legal system. Its characteristics could be listed as follows. First, stable and predictable legal system. India’s long-standing common law tradition offers businesses a reliable legal framework, unlike China’s more opaque system which can change unpredictably. Second, strong intellectual property protection. India has robust laws for protecting intellectual property, including patents, trademarks, and copyrights, making it attractive for tech companies and others reliant on IP. Third, increasing free trade agreements. India has signed numerous free trade agreements, reducing tariffs and trade barriers, thus facilitating easier export of goods and services. Fourth, Transparent Legal System. Indian legal system’s transparency helps businesses understand their rights and obligations more clearly compared to China’s. Fifth, Independent Judiciary. India’s judiciary is more independent, reducing the risk of arbitrary governance and cultivating a more welcoming attitude towards foreign investment than the Chinese government. This makes it easier for businesses to set up and operate in India (Rana & Joshi, 2022; Srikrishna, 2008).

To sum up, this PESTEL analysis highlights the complex relationship between India’s growth and its surrounding environmental factors. Politically, India is a stable and vibrant democracy with a slew of pro-industry policies and initiatives of the likes of Make in India that may have a positive impact on the country’s industrial growth and exports. Economically, a growing labour force and government schemes like the PLI and socially, a rising middle class, a young and educated workforce and a demographic dividend provide a strong base for economic growth. Technologically, India’s vibrant innovation ecosystem and skilled workforce position it well for technology exports. In addition, a stable legal system, intellectual property protection and a pro-business environment strengthen export-oriented industries. Environmentally, a focus on sustainability and environmental technologies supports cleaner exports. These insights help stakeholders navigate India’s diverse landscape effectively as it seeks to balance growth and tradition.

Economic Dissimilarities Between India And China

In the ever-evolving field of international business, analysing India’s trade with China is of utmost importance. The same provides a deeper look at the trade dynamics between these two major economies, highlighting significant trends, patterns and insights that define their bilateral trade relations. By examining the complexities of their commercial exchanges, this segment cements the contrast between India’s and China’s economic status.

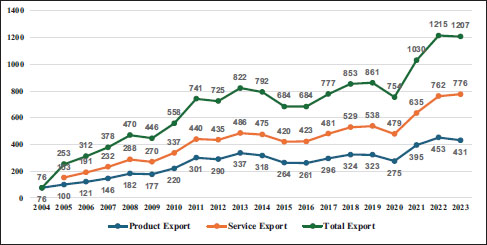

India’s Role in the Global Economy

India’s rising exports in goods and services highlight its growing role in the global economy, showcasing the competitiveness and appeal of Indian products and services in international markets. In recent years, the country has diversified its export portfolio. Traditional sectors like textiles, garments and pharmaceuticals remain key contributors, but there has been substantial growth in other domains such as IT services, software development and business process outsourcing (BPO). The country’s skilled workforce, technological expertise and cost advantages have been crucial in driving the expansion of these areas (Mishra, 2024).

Additionally, GOI initiatives like Make in India and the Services Exports from India Scheme have bolstered manufacturing–driven export growth. These programmes aim at enhancing India’s industrial capabilities and supporting the global expansion of its service-oriented sectors such as IT, healthcare and professional services. However, to fully realise the potential of India’s exports, challenges like limitations in infrastructure, complex regulatory processes and skill gaps must be addressed. Ongoing investments in infrastructure, regulatory simplifications and skill development programmes will be essential in sustaining this growth trajectory. Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 explain the continuously rising trend of India’s exports, especially, after the post-Covid recovery in the global supply chains (Mishra, 2024).

Figure 5. India’s Export Trend (in Billion Dollars).

Source: ITC Trade Map (2024).

Figure 6. China’s Export Trend (in Billion Dollars).

Source: ITC Trade Map (2024).

Figure 7. Exports as Percentage (%) of India’s and China’s GDP.

Source: ITC Trade Map (2024).

Figure 5 shows India’s exports of goods and services in Billions of US Dollars.

The rise in India’s exports could be attributable to the following. First, the rise of India’s manufacturing sector. India’s manufacturing sector has seen rapid growth in recent years, leading to increased production of exportable goods such as textiles, pharmaceuticals and engineering products. Second, growing demand for Indian goods in global markets. The demand for Indian goods has been rising globally due to factors like increasing affluence of consumers in developing countries, the growing popularity of Indian brands and a heightened focus on sustainability in global supply chains. Third, government’s focus on exports. The GOI has prioritised boosting exports through various measures, including providing incentives to exporters, signing free trade agreements and promoting the use of Indian ports as transhipment hubs (IBEF, 2024a; Mishra, 2024).

China’s Role in the Global Economy

Just like India, China too has experienced continuous growth in its exports, with its export volume being five times that of India over the past two decades. A key difference is that India’s exports have a higher proportion of services, whereas China’s growth is primarily driven by manufactured goods. China’s GDP growth rate has consistently outpaced India’s over the past few decades. However, India’s GDP growth rate has been catching up recently and in 2021, it surpassed China’s for the first time since 1990. Several factors contribute to the differences in GDP growth rates between the two countries. First, China’s economic reforms. Initiated in the late 1970s, these reforms spurred rapid economic growth by opening the economy to foreign investment, privatising state-owned enterprises and deregulating markets. Second, India’s economic reforms. Although India began its economic reforms in the early 1990s, these changes have been more gradual compared to China’s. India has also faced challenges such as corruption and infrastructural bottlenecks. Third, India’s demographics. With a young and growing population, India has significant potential for economic growth. However, high levels of poverty can impede this growth. Fourth, China’s demographics. An ageing population poses challenges for China, but the country benefits from a large pool of skilled workers, which supports sustained economic growth. It is too early to say whether India’s GDP growth rate will continue to catch up to China’s GDP growth rate. However, India has a number of strengths, such as a young population and a large market, which could help it achieve sustained economic growth in the years to come (Bukhari et al., 2024).

Exports as a percentage of GDP for both India and China have hovered around 20%, which is an ideal number for any economy. This indicates strong domestic consumption, helping both countries manage their vulnerabilities on account of external shocks and maintain a balanced dependence on foreign markets (ITC Trade Map, 2024).

In conclusion, India’s transformative journey in global exports highlights its economic dynamism and potential. The diversification of its export portfolio, driven by technological prowess and skilled labour force, demonstrates India’s adaptability to changing market demands. While initiatives like Make in India enhance its manufacturing prowess, addressing challenges such as infrastructural bottlenecks is crucial for sustained growth.

Comparing India’s trade with China reveals distinct economic trajectories. China’s manufacturing strength contrasts with India’s service-oriented growth, with both nations facing unique challenges. The evolving trade dynamics necessitate careful consideration of geopolitical, regulatory and environmental factors. As India seeks to position itself on the global stage, a balance of proactive policy measures, infrastructural improvements and innovative strategies will be the key.

Policies Related to Infrastructure and Scalability

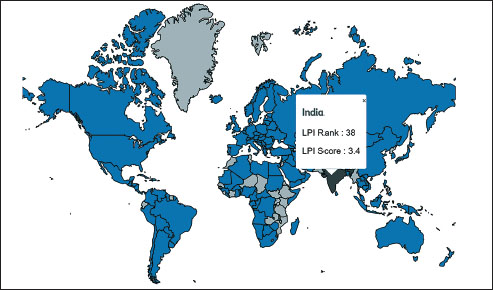

To compete with China and become a leading global sourcing destination, India must rapidly augment its trade and logistics infrastructure. This section examines India’s efforts to improve its trade and logistical capabilities to rival global leaders like China. In a highly competitive landscape, India’s goal to match China’s infrastructural strength is a significant motivator for transformation. It is essential to discuss the Logistics Performance Index (LPI), a key benchmark developed by the World Bank to evaluate trade-related infrastructure. The LPI assesses logistics friendliness through six dimensions, namely, customs, infrastructure, international shipments, logistics quality and competence, tracking and tracing and, timeliness. Another important measure is the Liner Shipping Connectivity Index (LSCI), which evaluates a country’s integration into the global liner shipping networks. By tracing India’s progress from modest LSCI scores to nearly 60; this segment highlights improvements in maritime connectivity driven by economic growth, port expansion and new shipping lines. This segment also explores strategic initiatives like the Pradhan Mantri Gati Shakti (PM Gati Shakti) Yojana and the National Logistics Policy (NLP), which are propelling India’s rise on these fronts. Finally, it examines the transformative potential of the Maritime India Vision 2030, detailing its promises of increased trade and investment, job creation and enhanced economic growth. If realised, these benefits could significantly reshape India’s maritime landscape and global trade influence (Kumar & Singh, 2022).

Logistics Performance Index

The LPI is an interactive benchmarking tool created by the World Bank to help countries identify challenges and opportunities they face in their performance on trade logistics and what they can do to improve the same. The LPI is based on a survey of international logistics professionals on the ground (global freight forwarders and express carriers), providing feedback on the logistics friendliness of the countries with which they trade. The survey covers six dimensions of logistics performance listed below. Each dimension is scored on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being the lowest score and 5 being the highest score. The overall LPI score is calculated as the average of the scores for the six dimensions as follows. Customs, Infrastructure, International shipments, Logistical quality and competence, Tracking and tracing, and Timeliness (World Bank, 2024b).

The LPI is an essential tool for countries aiming at enhancing their logistics performance. By identifying strengths and weaknesses across various dimensions, countries can pinpoint areas needing improvement. The LPI also serves as a benchmark for tracking progress over time. In the 2023 LPI, Singapore ranked first, followed by Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Hong Kong. India improved its position to 38th, climbing six places from the previous year (World Bank, 2024b) (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

It is evident from Table 1 that India has grown significantly from 2.90 in 2007 to 3.40 in 2023 as far as its LPI performance is concerned (Table 1). In order to be successful in growing as an export hub, India should be near China in this index for which it needs to work on all aspects of this index. China’s LPI rank is 19 and its score is 3.7 (World Bank, 2024b).

Figure 8. India’s LPI Rank and Score.

Source: World Bank (2024b).

Figure 9. China’s LPI Rank and Score.

Source: World Bank (2024b).

Table 1. LPI of India Versus China for the Years 2018 and 2023.

Source: World Bank (2024b).

Liner Shipping Connectivity Index

The LSCI gauges how well a country or port is integrated into the global liner shipping networks. There are five key components of the LSCI. Number of ships, their container carrying capacity, the maximum vessel size, the number of services and the number of companies deploying container ships in a country’s ports. The LSCI is a dimensionless measure, with a baseline value of 100 assigned to the country with the highest average index in 2004. Countries with higher LSCI scores are more integrated into the global liner shipping networks, providing them with better access to global markets. The LSCI can be utilised to compare the connectivity of different countries or ports, track changes in connectivity over time and identify countries or ports that may be underserved by the global liner shipping networks. The LSCI is a crucial tool for understanding the role of liner shipping in global trade and for formulating policies to enhance ports. By analysing the LSCI, policymakers can make informed decisions to improve the efficiency of the global supply chains and foster economic development. A comparison of the LSCI for various countries, including India and China, with benchmarks against Vietnam and the USA, reveals that India’s LSCI is consistently lower than China’s. This indicates a significant challenge for India in achieving smooth sea connectivity to major global trade hubs (UNCTAD, 2024) (Table 2 and Figure 10).

Table 2. Liner Shipping Connectivity Index.

Source: UNCTAD (2024).

Figure 10. Liner Shipping Connectivity Index.

Source: CEIC (2024).

Of late, India is improving its standing on the LSCI, thanks to GOI measures aimed at promoting free and fair trade and some factors as listed. First, Economic Growth. India’s expanding economy has increased the demand for imported goods. Second, Port Expansion. The development of Indian ports has facilitated easier access for ships. Last, New Shipping Lines. The introduction of new shipping routes serving India (UNCTAD, 2024).

The improvement in India’s LSCI is beneficial for the country’s economy, providing Indian businesses with better access to global markets, which can boost trade and investment. Additionally, it offers Indian consumers a wider range of imported goods (UNCTAD, 2024).

However, there is still room for improvement. India’s LSCI remains lower than that of some other countries, such as China and Vietnam, indicating potential for further enhancement in shipping connectivity (UNCTAD, 2024).

PM Gati Shakti Initiative

The PM Gati Shakti Yojana, launched by the GOI in October 2021, is a national infrastructure master plan aimed at integrating the planning and execution of infrastructural connectivity projects across the country. It seeks to enhance coordination among various ministries involved in these projects. Key features of the PM Gati Shakti Yojana include the following. First, digital platform. This platform will unite 16 ministries, including those responsible for railways, roadways and waterways, providing a single window for planning, execution and monitoring of infrastructure projects. Second, multi-modal connectivity. The plan emphasises developing multi-modal connectivity to facilitate seamless movement of people and goods across different transport modes, thereby, reducing logistics costs and improving economic efficiency. Third, project prioritisation. By fostering cross-sectoral interactions, the plan will prioritise projects and minimise implementation overlaps, ensuring that the most critical projects are addressed first. Fourth, transparency and accountability. The plan aims to enhance transparency and accountability in infrastructure project implementation through digital platforms and by involving all stakeholders in the decision-making process (India.Gov.in, 2024).

National Logistics Policy

In 2022, the Prime Minister launched the NLP to improve last-mile delivery, tackle transportation challenges, save time and resources for the manufacturing sector and achieve optimal speed in logistics. The NLP is a governmental framework introduced in 2022, aiming to enhance the logistics sector in India by making it more efficient, affordable and sustainable. The policy focuses on certain key areas. First, Infrastructure. The policy seeks to enhance logistics infrastructure, including roads, railways, ports, and airports. Second, Technology. It aims to leverage technology, such as blockchain and artificial intelligence, to boost logistics efficiency. Third, Regulation. The policy focuses on simplifying and streamlining logistics regulations, including customs clearance and cross border trade. Fourth, Skills. It aims to develop skills of the logistics workforce, including drivers, warehouse workers and IT professionals. Fifth, Finance. The policy intends to facilitate easier financing for logistics projects through loans and guarantees. Sixth, Sustainability. It aims to make the logistics sector more sustainable by reducing emissions and using recycled materials. Seventh, Collaboration. The policy promotes better collaboration among various stakeholders in the logistics sector, including government agencies, businesses and industry associations. Last, Ease of Doing Business. It aims at simplifying procedures and reducing paperwork to make logistics operations easier for businesses in India (Invest India, 2022).

Maritime India Vision 2030

The GOI has initiated efforts to improve the country’s ranking and ease of doing trade through the Maritime India Vision 2030. The Maritime India Vision 2030 is a bold initiative with the potential to revolutionise India’s maritime sector. If successful, it could significantly enhance trade and investment, generate employment and stimulate economic growth. Some of the key benefits of Maritime India Vision 2030 could be listed as follows. First, Boost in Trade and Investment. By enhancing India’s connectivity with the global maritime network, the MIV 2030 could facilitate easier import and export of goods, leading to increased economic growth. Second, Job Creation. The initiative could create numerous jobs in the maritime sector, including positions in ports, shipping and shipbuilding, thereby, boosting employment and reducing poverty. Third, Economic Growth. By making India more competitive in the global maritime markets, the MIV 2030 could attract more foreign investment and increase trade, contributing to higher economic growth (PIB, 2024).

Methodology

This thematic review of the literature study analyses existing work on transitioning global sourcing hubs from China to India. This article relies primarily upon academic databases, search engines and websites of the likes of Google Scholar, ProQuest, EBSCO Host, Web of Science and Research Gate to extract relevant studies for the theme. Besides, reports by relevant Departments/Ministries of the GOI and NGOs were also searched and used for the purpose. The same added a practical dimension to the usual academic rigour of this study; significant for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the theme. A total of 50 reference materials, including research papers, reports and websites have been used in this analysis. The main criteria for selecting the same is their relevance for the theme of this study in line with its primary research objective. To obtain as many pertinent articles as possible, this study makes extensive use of key words appropriate for the same. Some of them are being mentioned as follows. The first group of key words is related to the evolving global dynamics in a global context. The second collection of important words is relevant for India’s and China’s labour cost analysis in terms of an abundance of cheap labour. The third group pertains to the PESTEL analysis for India’s and China’s economies, keeping in view their political, commercial, social, technological, ecological and legal dimensions. Some of the relevant keywords are ‘global sourcing’, ‘PESTEL’, ‘NLP’, ‘Trends in India’s and China’s exports and imports’. Furthermore, the theme on ‘economic differences between India and China’ is identified with the help of important words such as ‘India’s role in the global economy’ and ‘China’s role in the global economy’. The last subject on ‘Policies on infrastructure and scalability’ is assessed with the help of words of the likes of ‘LPI’, ‘LSCI’, ‘NLP’, ‘Maritime India Vision 2030’ and ‘PM Gati Shakti’ initiative.

The ensuing chart summarises the conceptual framework followed in this study for analysis (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Flowchart for Methodology.

All in all, this study seeks to explore the transition of the global sourcing hub from China to India, driven by economic, political and social factors. The same aims to answer questions about whether India is overtaking China as a global sourcing hub, thereby, marking a paradigm shift in international trade logistics.

The subsequent section expounds the results and discussion for this article based on the analysis conducted thus far.

Results and Discussion

The main finding of this review article is the transitioning global sourcing hub from China to India in international logistics. The same is largely due to India’s competitive labour costs, thanks to an abundant labour force, favourable government policies and improving infrastructural facilities. The study concludes that while challenges on the fronts of customs, infrastructure, international shipments, logistical quality and competence, tracking and tracing and timeliness remain, India is poised to become a major player when it comes to global sourcing. Further research on the theme requires primary survey analysis of major stakeholders in international trade logistics. This could render more meaningful comparisons feasible. The next section concludes this study and elicits its future policy implications.

Conclusion and Future Policy Implications

To conclude, the challenges and opportunities related to India’s infrastructure and scalability for trade and logistics are crucial in determining its global role. As India strives to compete with China and become a global sourcing hub, the importance of strong logistics and shipping networks is paramount. The analysis of the LPI and the LSCI highlights both progress and areas needing improvement, when it comes to infrastructure and scalability. While there have been positive advancements, ongoing and strategic efforts are essential. Initiatives like the PM Gati Shakti Yojana, NLP and Maritime India Vision 2030 demonstrate the GOI’s resolve to address these challenges and promote sustainable development. India’s tenacity to turn these challenges into opportunities reflects its ambition to not only compete but also lead in global trade and commerce. By capitalising on these opportunities, India can enhance its economic growth and establish itself as a significant player in the ever-evolving landscape of international trade logistics.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Kanupriya  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4186-4070

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4186-4070

Atkinson, R. D., & Atkinson, R. D. (2024). China is rapidly becoming a leading innovator in advanced industries. Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

Balu, B., Jayapal, R., Gunupuru, K. R., & Mogili, R. (2022). A conceptual roadmap for implementing localization in the Indian automotive industry in a post-pandemic scenario. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 21(S1), 1–15. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Boopalan-Dr/publication/357736036_A_conceptual_roadmap_for_implementing_localization_in_the_indian_automotive_industry_in_a_post-pandemic_scenario/links/61dd30423a192d2c8af18e80/A-conceptual-roadmap-for-implementing-loc.implementing-localization-in-the-indian-automotive-industry-in-a-post-pandemic-scenario.pdf.

Brooks, S. G., & Wohlforth, W. C. (2015). The rise and fall of the great powers in the twenty-first century: China’s rise and the fate of America's global position. International Security, 40(3), 7–53.

Bukhari, S. R. H., Kokab, R. S., & Khan, E. (2024). The role of China in the global economy: Political strategies and economic outcomes. Spry Contemporary Educational Practices, 3(1), 558–576.

Buye, R. (2021). Critical examination of the PESTEL analysis model. Action Research for Development. https://scholar.google.co.in/scholar?q=Buye,+R.+(2021).+Critical+examination+of+the+PESTEL+analysis+model.+Action+Research+for+Development&hl=en&as_sdt=0&as_vis=1&oi=scholart

CEIC. (2024). Liner shipping connectivity index. https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/india/liner-shipping-connectivity-index.

Chandrasekhar, C. P., Ghosh, J., & Roychowdhury, A. (2006). The “demographic dividend” and young India’s economic future. Economic & Political Weekly, 41(49), 5055–5064. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4419004.

Christodoulou, A., & Cullinane, K. (2019). Identifying the main opportunities and challenges from the implementation of a port energy management system: A SWOT/PESTLE analysis. Sustainability, 11(21), 6046.

Debourdeau, A., Schäfer, M., & Berlin, C. B. T. U. (2021). Report on the PESTEL analysis of energy citizenship in Germany. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Ariane-Debourdeau-4/publication/370818446_Report_on_the_PESTEL_analysis_of_energy_citizenship_in_Germany/links/6464a66370202663165339b6/Report-on-the-PESTEL-analysis-of-energy-citizenship-in-Germany.pdf.

Deutch, J. (2018). Is innovation China’s new great leap forward? Issues in Science and Technology, 34(4), 37–47.

Dolgui, A., Ivanov, D., Sokolov, B., & Ivanova, M. (2017). Ripple effect in the supply chain: An analysis and recent literature. International Journal of Production Research, 56(1–2), 414–430.

Foreign Policy. (2023). Will India surpass China to become the next superpower? https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/06/24/india-china-biden-modi-summit-great-power-competition-economic-growth/.

Global Data. (2024). Labor cost index (LCI) of China. https://www.globaldata.com/data-insights/macroeconomic/labor-cost-index-lci-of-china-2137631/

HSBC. (2024). The next level: How Southeast Asia is moving up the value chain. https://www.business.hsbc.com/en-gb/insights/growing-my-business/the-next-level-how-southeast-asia-is-moving-up-the-value-chain.

IBEF. (2024a). About Indian economy: Growth rate & statistics. https://www.ibef.org/economy/indian-economy-overview.

IBEF. (2024b). India: A snapshot. https://www.ibef.org/economy/indiasnapshot/about-india-at-a-glance.

India.Gov.in. (2024). PM Gati Shakti national master plan. https://www.india.gov.in/spotlight/pm-gati-shakti-national-master-plan-multi-modal-connectivity.

International Economic Association. (2024). Projected labour force population of India and China. https://www.iea-world.org/indias-population-surpasses-china-but-challenges-await-in-workforce-expansion-a-deep-dive/.

Invest India. (2022). National logistics policy in India. https://www.investindia.gov.in/team-india-blogs/national-logistics-policy-india.

ITC Trade Map. (2024). https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx.

Jain, P., & Roy, A. (2024). Catalysts of innovation: Advancing India’s future through investments in basic science. In Unleashing the Power of Basic Science in Business (pp. 91–117). IGI Global.

Jena, D. K. (2024). Beyond technology: Exploring sociocultural contours of artificial intelligence integration in India. Educational Administration: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 1169–1184. https://doi.org/10.53555/kuey.v30i5.3031.

Kumar, V., & Singh, A. (2022). The ‘National Logistics Policy 2022’: An overview. Indian Journal of Law & Legal Research, 6(4), 1.

Lazard. (2024). The geopolitics of supply chains. https://www.lazard.com/media/d4dnwbvc/the-geopolitics-of-supply-chains.pdf.

Madhani, P. (2008). Global hub: IT and ITES outsourcing. SCMS Journal of Indian Management, 5(2), 108–114.

Manigandan, P., Alam, M. S., Murshed, M., Ozturk, I., Altuntas, S., & Alam, M. M. (2024). Promoting sustainable economic growth through natural resources management, green innovations, environmental policy deployment and financial development: Fresh evidence from India. Resources Policy, 90, 104681.

Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. (2021). One of the youngest populations in the world—India’s most valuable asset. https://indbiz.gov.in/one-of-the-youngest-populations-in-the-world-indias-most-valuable-asset/.

Mishra, M. K. (2024). Emergence of India as a key player in global economic affairs. ResearchGate. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.31037.06880.

Mitra, S. (2017). Politics in India: Structure, process and policy. Routledge.

Press Information Bureau (PIB). (2024). Maritime India vision 2030. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2080012.

Quitzow, R. (2015). Assessing policy strategies for the promotion of environmental technologies: A review of India’s National Solar Mission. Research Policy, 44(1), 233–243.

Raman, H. (2016). Dynamics of Indian economic growth: Can India become an economic powerhouse by 2025? https://www.jru.edu.in/wp-content/uploads/RMJ/vol-11/Dynamics%20of%20Indian%20Economic%20Growth.pdf.

Rana, R. S., & Joshi, A. (2022). Exploration of Indian legal system from past to present. Indian Journal of Law & Legal Research, 6(4), 1.

Shah, S. W. A., Afridi, S., & Madeeha, D. F. G. T. (2024). China’s world order. Remittances Review, 9(1), 2227–2239.

Singh, S., & Paliwal, M. (2015). India’s demographic dividend: In the context of its economic growth. World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues, 19(1), 146–157. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48505143.

Spoggi, G. (2020). Industry 4.0 and smart manufacturing: Potential environmental benefits. The case of China. http://dspace.unive.it/bitstream/handle/10579/18207/856705-1245335.pdf?sequence=2.

Srikrishna, B. N. (2008). The Indian legal system. International Journal of Legal Information, 36(2), 242–244.

Economy.com., The Global (2024). India: Political stability. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/India/wb_political_stability/.

UNCTAD. (2024). Maritime transport indicators. https://hbs.unctad.org/maritime-transport-indicators/.

Varghese, P. (2018). An India economic strategy to 2035: Navigating from potential to delivery. The Australian Government. https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/minisite/static/07db88b0-d450-4887-9c90-31163d206162/ies/pdf/dfat-an-india-economic-strategy-to-2035.pdf.

World Bank. (2024a). India at a glance. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/india/overview#1.

World Bank. (2024b). Logistics performance indicators. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/logistics-performance-index-(lpi).

Yang, D. T., Chen, V., & Monarch, R. (2010). Rising wages: Has China lost its global labor advantage? https://repec.iza.org/dp5008.pdf.

Zhang, B., Zhu, H., & Zhang, J. (2023). A portrait of China’s economic transformation: From manufacturing to services. China Economic Journal, 16(1), 14–27.

Zhao, C. (2023). Decoding China’s thriving supply chain ecosystem. FDI China. https://fdichina.com/blog/supply-chains/