1School of Management, Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

2Department of Professional Accounting and Finance, Kristu Jayanti College (Autonomous), Bengaluru, Karnataka, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The agricultural and food production value chain is crucial for both economic development and food security, playing a vital role in global economies. Achieving sustainable financial inclusion (SFI) in this sector poses a considerable challenge. Land banking (LB) refers to the process of leasing unused land held by farmers through agreements with organizations and active farmers. This research employs structural equation modeling (SEM) to explore the relationships among key factors that influence workforce empowerment and their impact on SFI within the agri-food and land-use value chain. This framework aimed at promoting SFI develops strategies applicable across various sectors and involves investors through a responsible governance model. The research draws on insights from diverse stakeholders, such as farmers, agribusinesses, financial organizations, and policymakers, to create a comprehensive model for improving financial inclusion within the industry.

Agri-food and land-use value chain, employment and equality, sustainable financial inclusion, balanced ecosystem, affordable clean energy access

Introduction

In an era characterized by unparalleled global difficulties, it has become essential to strive for sustainable economic growth and inclusive development. The agri-food and land-use sectors play a vital role in economies around the globe. The interconnection between agriculture, food production, and land management not only has major effects on food security and environmental sustainability but also serves as a fundamental aspect of livelihoods for a large segment of the global population. The agri-food and land-use value chain are an essential area with significant consequences for economic stability, food security, and sustainable development. Ensuring financial inclusion in this context is crucial for promoting economic growth and reducing poverty.

This framework highlights the potential of sustainable land-use value chains to alleviate poverty by creating job opportunities for residents of rural areas in emerging economies. The agri-food and land-use sectors are crucial for the livelihoods, survival, and economic progress of billions of people around the globe. Its essential role in ensuring food security and promoting economic development emphasizes its importance in both developed and developing nations (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [FAO], 2020). Nevertheless, attaining sustainable financial inclusion (SFI) within this sector poses a complicated challenge. Financial inclusion, which refers to the provision of accessible and affordable financial services to all individuals, is not only an economic necessity but also a basic human right (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018). In this scenario, empowering the workforce emerges as a vital element in improving financial inclusion within the agri-food and land-use value chain.

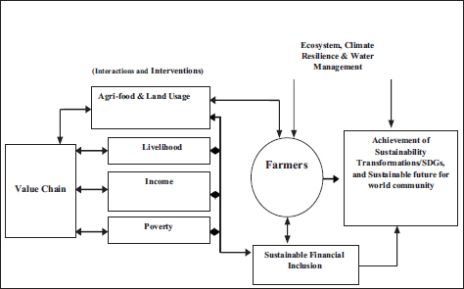

Figure 1 sets forth an extensive array of goals designed to promote sustainable development in rural regions. These goals encompass the pursuit of sustainable, decent employment and economic advancement, the integration and enhancement of the agri-food and land-use value chain for regional advancement, and the tackling of widespread challenges, such as poverty and unemployment faced by rural communities. Furthermore, there is an emphasis on transitioning agriculture toward sustainable organic farming methods, creating avenues for global market access for agricultural goods, and supporting a balanced ecosystem that includes the environment, water resources, and climate initiatives. In addition, the framework highlights the need to deliver vital services such as education, healthcare, food security, clean drinking water, and sanitation for rural residents while also ensuring access to affordable clean energy, addressing inequalities, and championing gender equality throughout the area. Ultimately, the framework aims to secure the livelihoods of rural communities by establishing peace, justice, and strong institutions, thereby contributing to a sustainable future.

Figure 1. Conceptual Model.

Literature Review

The involvement of groups may pertain to either agricultural activities or the subsequent value chain of organic products, especially after these products are processed for export or local market sales (Costanza et al., 2016). Establishing sustainable farming and non-farming collectives is crucial for enrolling every unemployed person in rural communities, providing education and training on transformation, and appropriately assigning them according to their skills and capabilities, particularly in organic agriculture and related fields (Griggs et al., 2013). Unemployed groups, in collaboration with supportive partners, can engage in acquiring expertise, securing funding, utilizing technology, managing supply chains and logistics, and marketing agri-food products in global markets, aided by state and government support (Mathy & Blanchard, 2016). Transforming the rural population into self-sufficient communities is one of the key goals aimed at addressing the financial challenges faced by millions of individuals living in rural areas who strive for survival and livelihood (Morgan, 2009). By enabling the rural community to cooperate, partner, and form groups with agricultural stakeholders, the unemployed can actively participate as a workforce in organic farming and land-use value chain initiatives (Sidney et al., 2017). Although this framework can benefit individuals across India, it particularly focuses on overcoming the employment challenges faced by rural residents, aiding their financial inclusion through a systematic and organized approach (Buse & Hawkes, 2015). Various initiation processes involve connecting group members through agricultural collaboration contracts, land banking (LB), funding sources, production planning methods, hiring specialists, and seeking assistance from governmental bodies (Hiç et al., 2016). This can be achieved by leveraging their potential in agri-food development and constructing an effective land-use value chain that grants them opportunities to advocate for a dignified and equitable living (Fahy & Cinnéide, 2009). This proactive framework is intended to structure all activities in a planned manner, supporting rural communities, sustainable agriculture, and improved livelihoods, ultimately leading to coordinated efforts for sustainable regional growth and contributing to overall advancement within the agri-food and Agribusiness landscape in rural areas (Parker, 2006). There is a system in place for agricultural landowners to pool their lands into a common land bank platform, achieved through education, planning, networking, implementation, coordination, monitoring, and support for each farmer, all governed under this land-use value chain (Trier & Maiboroda, 2009). This framework relies on a governance structure that emphasizes the integration of all involved individuals and stakeholders, along with all relevant activities, to ensure the organization and execution of the entire framework and to connect groups within the regional value chain (Wood, 2005). This sustainable governance structure fosters a collective sustainable agenda that aligns the interests of local communities, which play a vital role in achieving successful transformation and value chain operations, with a profit-sharing system in place for all involved (Bue & Klasen, 2013). This framework indicates its mission of prosperity through necessary structural modifications and changes aimed at impacting the agri-food and land-use value chain ecosystem, initially focusing on selected rural areas (Smith & Olesen, 2010). Engaging skilled researchers and competent authorities at the request of state and central governments has significantly affected rural development (Klinsky et al., 2010). A large portion of the global population depends on the agri-food and land-use sectors for their livelihood, income, and employment, which serve as foundational elements of worldwide economies (FAO, 2020). Nonetheless, achieving SFI in this sector has proven challenging. To alleviate poverty, promote economic growth, and foster sustainable development, financial inclusion—defined as the availability and accessibility of financial services for all societal segments—is crucial (Demirguc-Kunt et al., 2018). Empowering workers is a vital aspect of maintaining financial inclusion in the agri-food and land-use value chain. In this context, empowerment entails equipping individuals with the information, tools, and resources necessary for successfully engaging in business ventures and financial activities (Asian Development Bank [ADB], 2021). Research by Morduch and Haley (2018) indicates that empowering initiatives such as access to formal banking services and financial literacy training can enhance financial outcomes for individuals employed in agriculture. Similarly, the significance of digital technology in empowering agricultural labor cannot be overstated. The rise of mobile banking, digital payment platforms, and fintech solutions has vastly improved access to finance for people in remote and underserved agricultural areas (World Bank, 2019). Studies conducted by Mas and Morawczynski (2009) and Demirguc-Kunt et al. (2018) highlight the transformative impact of digital financial services on financial inclusion and the efficiency of business operations within the agri-food value chain.

With the advancement of technology, the establishment of policy and regulatory frameworks is essential for advancing long-term financial inclusion. Governments and international bodies are increasingly recognizing the importance of creating an environment that promotes financial inclusion and entrepreneurship within the agri-food sector (UNCDF, 2020). Financial inclusion initiatives can be bolstered through actions such as targeted lending programs, subsidy initiatives, and changes to regulations (CGAP, 2021). Nevertheless, several challenges remain that hinder SFI within the agri-food and land-use value chain. Factors such as low financial literacy, inadequate infrastructure, and regulatory limitations continue to impede progress (ADB, 2021). Women often encounter significant obstacles to financial inclusion, with gender disparities in access to financial services remaining a critical issue (World Bank, 2020).

Conceptual Framework

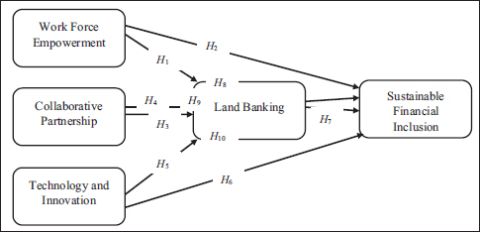

Figure 2 conceptual framework reveals the relationship between Workforce Empowerment, Collaborative Partnership, and Technology & Innovation on Sustainable Financial Inclusion. Land Banking serves as a mediating variable, enhancing the effects of these variables. The model suggests that Land Banking helps translate efforts in workforce empowerment, collaboration, and innovation into sustainable financial access and benefits. Testing the 10 hypotheses will validate these relationships and determine the extent of Land Banking’s role as a catalyst.

Problem Statement

The lack of sufficient financial inclusion and access to vital financial resources and services continues to be disproportionately limited for a large segment of stakeholders involved in the agri-food and land-use value chain. Even though it is crucial, the agri-food and land-use value chain frequently encounters issues such as financial exclusion, restricted access to credit, and insufficient empowerment of its workforce. Tackling these issues requires a thorough understanding of the complex relationships among important variables.

Figure 2. Conceptual Framework.

Research Objectives

To improve the agri-food and land-use value chain for regional progress in encouraging sustainable organic farming practices in agriculture while ensuring a balanced ecosystem that encompasses environmental health, water resources, and resilience to climate change.

Hypothesis

Methodology

This research adopts a quantitative methodology to explore the interconnections among workforce empowerment, financial inclusion, and sustainability within the agri-food and land-use value chain. Structural equation modeling (SEM) will be employed to investigate the causal relationships among the critical factors. The focus of the study is on individuals performing various roles in this value chain, including farmers, agricultural laborers, agribusiness professionals, and policymakers. To achieve fair representation, a multistage stratified sampling technique will be implemented. Initially, participants will be categorized based on their geographical regions and subsequently divided according to their specific roles and responsibilities. A power analysis of 0.80 at a 0.05 level of significance was conducted using multiple regression analysis with five predictors to determine the necessary sample size based on the effect size. For identifying a moderate effect, a sample size of 92 is required for multiple regression with five predictors, whereas for a small effect, a sample size of 395 is required. Thus, a total of 420 is sufficient for carrying out the SEM analysis. A total of 420 participants provides a robust basis for statistical analysis and model evaluation.

Data Analysis

The research assessed the dependability, validity, and robustness of a model that included both measurement and structural components. The findings indicated strong internal consistency and convergent validity, with factor loadings exceeding 0.7 and variance inflation factor values remaining under 2.0. Discriminant validity was established through interconstruct correlations, with the strongest correlation identified between LB and CP. Workforce empowerment positively influenced LB significantly, while technology and innovation exerted the most considerable impact on LB. Workforce empowerment and CP had significant direct effects on SFI. A mediation analysis indicated partial mediation in the pathways WE .png) LB

LB .png) SFI and CP

SFI and CP .png) LB

LB .png) SFI, but not in the case of TI

SFI, but not in the case of TI .png) LB

LB .png) SFI.

SFI.

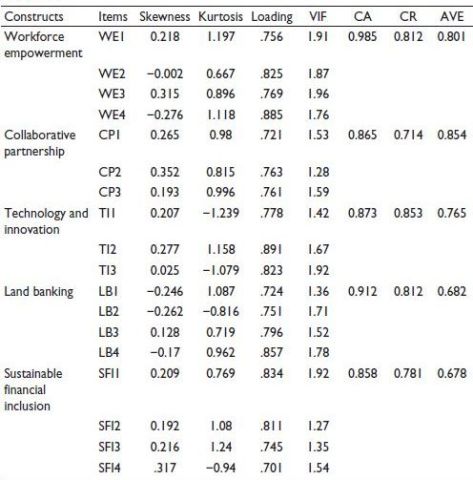

Table 1. Assessment of Measurement Model: Constructs, Items, and Reliability Indicators.

The test results in Table 1 measurement model represents the initial phase of SEM, composed of five lower-order constructs. The model’s validity is assessed through Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. The data exhibit a normal distribution, with indicator loadings exceeding 0.7 and Cronbach's alpha surpassing the established threshold. The SEM evaluates the relationships, with a good model fit requiring values greater than 0.90, RMSEA ranging from 0.05 to 0.08, and SRMR lower than 0.05.

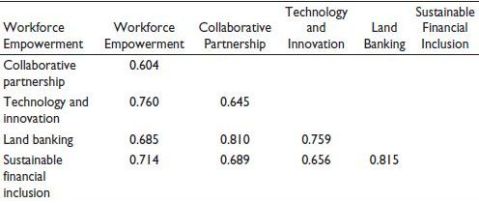

Table 2. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Interconstruct Correlations.

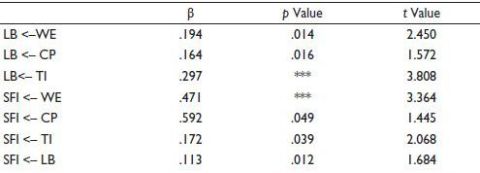

Table 3. Path Coefficients and Statistical Significance of Structural Model.

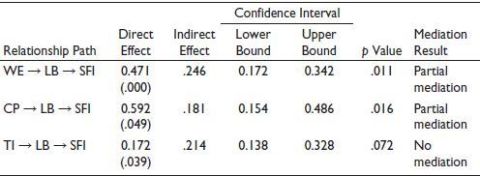

Table 4. Mediation Analysis: Direct and Indirect Effects with Confidence Intervals.

Discriminant validity, assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), was confirmed by calculating ratios below the 0.85 threshold, indicating the constructs' distinctness from others.

The research assesses how workforce empowerment, CPs, technology, and innovation influence LB and SFI. It revealed that these elements have a significant effect on LB, CPs, and technology. The squared multiple correlation for LB is 0.765, suggesting that these factors explain 76.5% and 58.3% of the variance in LB, respectively. The results confirm the hypotheses H1, H3, H4, H6, and H7.

The test results in Table 2 analysis reveals strong interconnections among key factors, with technology and innovation demonstrating the highest correlation with land banking (0.810) and a significant relationship with sustainable financial inclusion (0.689). Collaborative partnership also plays a crucial role, particularly in driving financial inclusion (0.714) and land banking (0.685). Additionally, sustainable financial inclusion (0.815) emerges as a central element, reinforcing the impact of these interconnected factors in fostering workforce empowerment and economic growth.

The test results in Table 3 highlights the influence of workforce empowerment (WE), collaborative partnership (CP), and technology & innovation (TI) on land banking (LB) and sustainable financial inclusion (SFI). Land banking (LB) is positively affected by workforce empowerment (0.194, p = .014, t = 2.450) and technology & innovation (0.297, p < .001, t = 3.808), with technology & innovation exerting the strongest impact. However, collaborative partnership (0.164, p = .016, t = 1.572) has a relatively weaker influence on LB. Similarly, sustainable financial inclusion (SFI) is significantly influenced by workforce empowerment (0.471, p < .001, t = 3.364), indicating that a well-empowered workforce enhances financial inclusion. Technology & innovation (0.172, p = .039, t = 2.068) also plays a role, though its impact is smaller. While land banking (0.113, p = .012, t = 1.684) does contribute to SFI, its effect is relatively limited. Additionally, collaborative partnership (0.592, p = .049, t = 1.445) positively affects SFI, but its influence is not as strong as that of workforce empowerment. Overall, technology & innovation emerges as the most critical factor for Land banking, underscoring the importance of digital advancements in asset management. At the same time, workforce empowerment plays a central role in driving sustainable financial Inclusion, emphasizing the need for financial literacy and skill development. While collaborative partnership moderately supports both LB and SFI, it is not the primary driver. Lastly, the relatively weak impact of Land banking on financial inclusion suggests that while land asset management is relevant, other factors such as workforce empowerment and technology have a greater influence on financial inclusion outcomes.

The test results in Table 4 indicated that LB partially influences the connection between workforce empowerment and SFI. Workforce empowerment demonstrated a positive indirect impact on SFI, while CPs exhibited both a positive indirect effect and a direct effect. Although technology and innovation had an insignificant indirect impact on SFI, their direct effect was also positive and significant. As a result, LB does not act as a mediator in the relationship between technology and innovation and SFI. These results imply that LB is essential for fostering SFI.

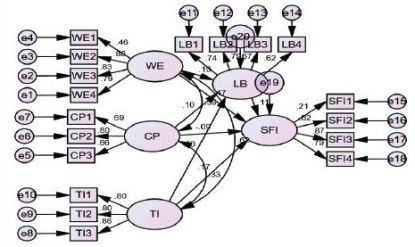

Figure 3 examines the impact of various factors on sustainable financial inclusion. It measures workforce empowerment (WE), collaborative partnership (CP), technology and innovation (TI), land banking (LB), and sustainable financial inclusion (SFI). Factor loadings are above 0.6, indicating good reliability of indicators. Path coefficients show significant positive relationships between WE, LB, and SFI. WE has a moderate effect on LB, while CP has a weak positive effect on LB. LB acts as a partial mediator, receiving inputs from WE, CP, and TI, and strongly affecting SFI. The model appears structurally valid, but collaborative partnerships may need re-evaluation or better structuring for meaningful impact.

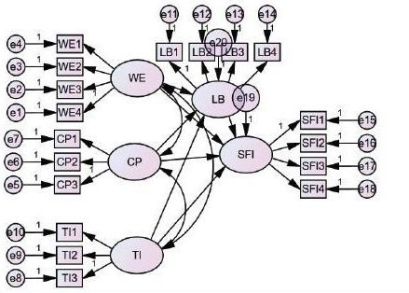

Figure 4 is a default standardized model used for SEM estimation in software like AMOS, LISREL, or SmartPLS. It includes key constructs like WE, CP, TI, LB, and SFI. The model’s paths and hypotheses are represented by the same hypotheses from the conceptual model. The model’s fit is evaluated using fit indices, and results can be interpreted to interpret causal strength and mediation effects.

Figure 3. Structural Model with Regression Co-efficient.

Figure 4. Empirical Model.

Result and Discussions

The value chain of agri-food and land-use is vital for the world’s economies, playing a significant role in economic development and food security. Achieving financial inclusion continues to be a challenge. LB, which involves leasing unused rural land, has emerged as a viable solution. A framework for SFI is proposed, incorporating various stakeholders and a structure for sustainable governance. The results emphasize the importance of consolidating all operations within the agri-food and land-use value chain ecosystem to foster sustainable development and rural progress. Workforce empowerment encompasses financial literacy education, the adoption of digital technologies, and supportive policy frameworks. The research indicated that 76.5% of the variance in LB can be explained by these factors, highlighting a significant mediating role of LB in the connection between workforce empowerment and SFI. While LB partially mediated the relationship between CPs and SFI, it did not serve as a mediator in the link between technology and innovation and SFI.

The research also examines how workforce empowerment, CPs, technology, and innovation influence LB and SFI, as well as technology and innovation. The findings indicate that these elements account for 76.5% of the variance in LB. The study demonstrates a positive and significant mediating effect of LB in the connection between workforce empowerment and SFI, highlighting a noteworthy indirect impact of workforce empowerment on SFI. Additionally, it reveals that LB partially mediates the relationship between CPs and SFI. However, it does not act as a mediator between technology and innovation and SFI.

The value chain associated with agri-food and land use is vital for economic development and food security, yet persistent financial inclusion remains a challenging issue. LB involves leasing unused lands owned by farmers in rural areas through agreements with workforce organizations and active farmers. Empowering the workforce is crucial for attaining SFI within the agri-food and land-use value chain. Such empowerment includes initiatives like financial literacy education, embracing digital technologies, and developing supportive policy frameworks.

The agri-food and land-use value chain are the key engine for economic growth and food security. Financial inclusion, on the other hand, is a long-standing challenge, especially at the rural level. This research identifies LB as a viable tool to meet financial exclusion by leasing idle rural land and incorporating it into a governance framework. The results indicate that workforce empowerment in the form of financial literacy education, digital technology adoption, and enabling policy frameworks strongly determines LB. All these factors together explain 76.5% of LB variance. Also, LB has a significant mediating effect in bridging workforce empowerment and SFI, which confirms that empowering the workforce in the agri-food value chain leads to economic sustainability.

The research also discovers that LB partially mediates the relationship between CPs and SFI. This indicates that developing robust partnerships between agricultural stakeholders, financial institutions, and policymakers strengthens the effectiveness of financial inclusion initiatives. LB is not a mediator in the relationship between technology, innovation, and SFI. This means that although technological innovation propels productivity and efficiency, it is not necessarily going to impact financial inclusion directly unless part of a larger ecosystem involving land ownership and financial access. The study emphasizes the need to consolidate activities in the agri-food and land-use value chain ecosystem to attain long-term sustainability and rural development. Workforce empowerment strategies, especially through digital financial instruments and training, are critical in solving economic inequalities and promoting fair access to financial services.

Recommendation

The agri-food and land-use value chain are vital for global economies, and maintaining financial inclusion is critical. LB, which involves leasing out underutilized rural land, presents a promising solution. Strategies for empowering the workforce, such as providing financial literacy education and promoting the use of digital technologies, are essential for fostering SFI. The research indicates that 76.5% of the variance in LB is linked to workforce empowerment, which mediates the connection between workforce empowerment and SFI. Additionally, LB partially mediates the relationship between CPs and SFI. The results underscore the significance of LB and workforce empowerment in attaining SFI within the agri-food and land-use value chain.

Implication

To enhance financial inclusion in the agri-food and land-use value chain, a multistakeholder response is required. Enhancing workforce empowerment programs through financial literacy training and digital education should be intensified to ensure rural workers, farmers, and stakeholders are able to participate effectively in LB schemes and access financial services. The use of digital financial solutions, including blockchain-based land registry, mobile banking, and digital payment systems, should be encouraged to make LB more efficient and enhance credit access for small-scale farmers. Governments and financial regulators must come up with policies that support land leasing contracts, secure tenure rights, and establish financial incentives for agribusiness investments. Moreover, strengthening cooperative partnerships among agricultural cooperatives, technology providers, and financial institutions will develop a more inclusive financial system that is favorable to rural communities. Blending sustainable farming practices into the LB process will guarantee conservation of the environment while enhancing farmers' economic opportunities.

Policymakers ought to create a regulatory environment for LB to provide secure tenure agreements and avert land holdings. Financial incentives in the form of subsidies, low-interest loans, and tax advantages should be given to promote lending by financial institutions to small farmers and agri-entrepreneurs. Public–private partnerships should be used to drive digital financial inclusion, especially in rural regions. Financial inclusion and LB programs also need to be aligned with Sustainable Development Goals to make these programs sustainable and promote long-term economic growth.

Conclusion

The article ends by highlighting the main findings and their importance for realizing SFI within the agri-food and land-use value chain. The proposed conceptual framework underscores the necessity of integrating all components of the agri-food and land-use value chain ecosystem to foster sustainable growth and rural development, ultimately creating resilient communities. This necessity has recently emerged, prompting initiatives to pinpoint the factors that foster rural development by introducing innovative ideas and concepts to shape this framework and develop sustainable communities in rural settings by enhancing the agri-food and land-use value chain ecosystem. In summary, empowering the workforce is crucial for attaining SFI in the agri-food and land-use value chain. This empowerment involves a variety of strategies, such as training in financial literacy, embracing digital technologies, and enacting supportive policy measures. Although considerable progress has been made, continued targeted efforts are essential to tackle ongoing challenges and ensure equitable access to financial services and economic opportunities for everyone in this sector.

This research brings to the fore the central role of LB and workforce empowerment as drivers of SFI in the agri-food and land-use value chain. The conceptualized framework for the study underlines the necessity of converging all the components of the value chain system in initiating sustainable growth as well as rural development. Through initiatives of financial exclusion by organized LB, rural communities attain economic resilience and sustainability. Key results show that LB greatly mediates the role of workforce empowerment and SFI. Nevertheless, its impact is less when it applies to technology and innovation, suggesting that more studies are required to investigate how advancements in technology can enhance financial inclusion initiatives. To achieve the potential of financial inclusion in the agri-food industry, targeted policy interventions, collaborative programs, and workforce training schemes need to be given high priority. Although significant progress has been made, ongoing efforts are necessary to address recurrent challenges and provide inclusive financial access for all those involved in the sector.

Future studies need to work toward establishing SFI models, which incorporate new technologies such as blockchain and AI, into the agri-food and land-use value chain. Moreover, research needs to examine the sociocultural obstacles to financial inclusion in rural communities and recommend interventions to overcome them. Research into the long-term effects of LB on rural livelihoods and economic mobility will also contribute further to policy and strategic decision-making. This research accepts some limitations, such as the specificity of its geographical and economic context, the dynamic nature of financial policies, and the use of secondary literature as the source for some elements of the analysis. In addition, socioeconomic and cultural factors driving financial inclusion in rural areas can differ across regions. In spite of these limitations, the study offers useful information and practical recommendations to promote SFI in the agri-food and land-use value chain.

Scope for Future Research

Future studies will concentrate on developing sustainable strategies for financial inclusion in the agri-food and land-use value chain, with an emphasis on empowering the workforce. The research will incorporate various ecosystem activities to promote growth and development in rural areas. Empowering the workforce will be key to attaining SFI, which will include training in financial literacy, the adoption of digital technologies, and the establishment of supportive policy frameworks. The study will seek to identify and tackle barriers to ensure that all individuals have equal access to financial services and opportunities for economic progress.

Limitations

The study concentrates on improving financial inclusion within the agri-food and land-use value chain, while recognizing constraints such as the particularity of the context, the evolving economic and policy environments, dependence on established literature, and the various socioeconomic and cultural conditions in rural settings. Nonetheless, this research offers meaningful insights and actionable suggestions for upcoming initiatives.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Naveen Kumar R  https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6566-0862

https://orcid.org/0009-0002-6566-0862

Asian Development Bank. (ADB). (2021). Empowering women in agriculture through access to finance. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/758581/adbi-brief-women-economic-empowerment.pdf

Bue, M. C. L., & Klasen, S. (2013). Identifying synergies and complementarities between MDGs: Results from cluster analysis. Social Indicators Research, 113(2), 647–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0294-y

Buse, K., & Hawkes, S. (2015). Health in the sustainable development goals: Ready for a paradigm shift? Globalization and Health, 11(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-015-0098-8

CGAP. (2021). Financial inclusion and the agriculture value chain. https://www.cgap.org/financial-inclusion

Costanza, R., Fioramonti, L., & Kubiszewski, I. (2016). The UN sustainable development goals and the dynamics of well-being. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(2), 59–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1231

Demirguc-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., Ansar, S., & Hess, J. (2018). The global Findex database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. World Bank. https://academic.oup.com/wber/article/34/Supplement_1/S2/5700461

Fahy, F., & Cinnéide, M. Ó. (2009). Re-constructing the urban landscape through community mapping: An attractive prospect for sustainability? Area, 41(2), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2008.00860.x

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). (2020). The state of food and agriculture 2020. https://www.fao.org/3/cb1447en/cb1447en.pdf

Griggs, D., Stafford-Smith, M., Gaffney, O., Rockström, J., Öhman, M. C., Shyamsundar, P., Steffen, W., Glaser, G., Kanie, N., & Noble, I. (2013). Policy: Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature, 495(7441), 305–307. https://doi.org/10.1038/495305a

Hiç, C., Pradhan, P., Rybski, D., & Kropp, J. P. (2016). Food surplus and its climate burdens. Environmental Science & Technology, 50(8), 4269–4277. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5b05088

Klinsky, S., Sieber, R., & Meredith, T. (2010). Connecting local to global: Geographic information systems and ecological footprints as tools for sustainability. The Professional Geographer, 62(1), 84–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330120903404892

Mas, I., & Morawczynski, O. (2009). Designing mobile money services lessons from M-PESA. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization, 4(2), 77–92.

Mathy, S., & Blanchard, O. (2016). Proposal for a poverty–adaptation–mitigation window within the green climate fund. Climate Policy, 16(6), 752–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1050348

Morduch, J., & Haley, B. (2018). Financial inclusion, financial education, and financial well-being: Evidence from rural economies. Oxford University Press, United Kingdom.

Morgan, A. D. (2009). Learning communities, cities and regions for sustainable development and global citizenship. Local Environment, 14(5), 443–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830902903773

Parker, B. (2006). Constructing community through maps? Power and praxis in community mapping. The Professional Geographer, 58(4), 470–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9272.2006.00583.x

Sidney, J. A., Jones, A., Coberley, C., Pope, J. E., & Wells, A. (2017). The well-being valuation model: A method for monetizing the nonmarket good of individual well-being. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology, 17(1), 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10742-016-0161-9

Smith, P., & Olesen, J. E. (2010). Synergies between the mitigation of, and adaptation to, climate change in agriculture. The Journal of Agricultural Science, 148(5), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859610000341

Trier, C., & Maiboroda, O. (2009). The Green Village project: A rural community’s journey towards sustainability. Local Environment, 14(9), 819–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830903166487

Wood, J. (2005). How green is my valley? Desktop geographic information systems as a community-based participatory mapping tool. Area, 37(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00618.x

World Bank. (2019). The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring financial inclusion and the fintech revolution. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/ed800062-e062-5a05-acdd-90429d8a5a07

World Bank. (2020). Women, business, and the law 2020. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/7502ec1b-038c-557d-849d-4fc4b26ff6fb