1School of Business, RV University, Bangalore, Karnataka, India

2Management Department, Sardar Patel University, Vallabh Vidyanagar, Anand, Gujarat, India

The advertising sector’s evolution due to new media has led to a focus on social networking sites (SNSs) for reaching core audiences affordably. Video advertising on platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and Facebook is gaining momentum. A survey with 356 respondents across demographics revealed strong positive relationships between advertising value perception and attitudes, as well as insights into higher-order constructs like brand love, analyzed through structural equation modeling (SEM). The study underscores the importance of trustworthy, authentic ads in addressing consumer concerns for increased value perception. It provides a model for effective advertising strategies on SNSs in India, emphasizing entertainment and information value while addressing authenticity and privacy issues.

Social networking sites, video advertising, brand love, advertising value perception, attitude

Introduction

In today’s marketing and communication landscape, digital technology has drastically changed how businesses engage with their customers (Pahari et al., 2024). To reach a broad audience, advertisers are now showing interest in unconventional media, such as social networking sites (SNSs), to connect with their target audience. This audience is especially the “Generation Y,” also popularly known as “millennials.” Due to their early exposure to digital interactive media, millennials find it impossible to picture their existence without the digital world. Since they received a sizable inheritance from their Baby Boomer parents, who were born between 1946 and 1964 (Kim & Kim, 2018). Given these circumstances, researchers are motivated to investigate how millennials perceive the value of advertising on SNSs like YouTube, Facebook, and Instagram (Saxena & Khanna, 2013). Understanding their attitudes and behaviors toward advertising on these platforms can provide valuable insights for marketers aiming to effectively target this influential demographic.

The internet, smartphone applications, social media, and other digital communication technologies have become deeply ingrained in the daily lives of billions of people across the globe. As of 2024, the estimated number of internet users worldwide was 5.5 billion, up from 5.3 billion in the previous year. This share represents 68% of the global population (Statista, 2024). Among the countries with significant internet usage, India stands out due to its massive population and high internet penetration rate. The internet serves a wide range of purposes for most individuals, such as conducting Google searches, accessing emails, online shopping, watching videos and movies, utilizing social media platforms, and engaging in instant messaging.

According to Kaplan and Haenlein (2010), SNSs are a variety of internet-based applications that are built on the theoretical and technological underpinnings of Web 2.0 and that enable the creation and exchange of User Generated Content. The expected outcome is that SNSs will greatly influence buying choices as individuals’ actions and viewpoints get shared through these platforms. Capitalizing on this opportunity, marketers have begun utilizing SNSs as a means of advertising. Rizavi et al. (2011) state that SNSs serve as a powerful platform for advertising, attracting millions of users from diverse nations, speaking various languages, and belonging to different demographics.

SNSs have opened innovative avenues for businesses to interact with customers. These platforms are of immense importance, as they provide businesses with a large advertising platform, attracting millions of multilingual visitors from diverse nations and demographics (Rizavi et al., 2011). Given the significant impact of social media on people’s lives, businesses are now turning to more cost-effective online advertising channels, including blogs, SNSs, email marketing, website adverts, among others (Saxena & Khanna, 2013). Consequently, many companies have shifted their advertising expenditures from traditional platforms to social media platforms (Lee & Hong, 2016). This shift enables businesses to engage with their clients directly, swiftly, and economically (Kaplan & Haenlein, 2010). Recognizing the effectiveness of SNSs for marketing products, companies worldwide have increased their SNSs advertising budgets to promote their products and services, leading to a surge in revenue for social networking website companies (Saxena & Khanna, 2013).

As per research conducted by Sprout Social (2018), 91% of consumers are inclined to trust a brand that maintains a presence on social media, enabling them to engage with the brand. Considering the increasing trend of advertising on SNSs, particularly in emerging economies like India, it becomes crucial to investigate the key factors that contribute to the perception of advertising value. Furthermore, understanding its impact on attitudes, purchase intentions, brand loyalty, and electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) is of paramount importance.

Numerous studies have examined the factors influencing the success of web advertising (Berthon et al., 1996; Brown et al., 2007; Ducoffe, 1995). However, it is important to note that these studies primarily focused on conventional websites and not on SNSs (Saxena & Khanna, 2013). Advertising on SNSs differs in several ways compared to traditional websites. First, the delivery of advertisements on SNSs can vary, with some messages being “pushed” to consumers, while others are based on “pull” content (Taylor et al., 2011). Second, the user-to-user interface on SNSs has its unique characteristics (Brake & Safko, 2009). Lastly, the global number of SNS users is continuously increasing, making this platform highly appealing for advertising purposes. However, little is known about the true value of advertisements on SNSs. The present study aims to bridge this research gap and shed light on this topic.

Literature Review

Existing literature was studied in detail.

Advertising Value Perception

Ducoffe (1995) introduced the concept of the advertising-value construct to gauge consumers’ perceptions regarding the relative worth or usefulness of advertising. Through a series of research studies, Ducoffe (1995, 1996) developed a model that considered three factors influencing value perception: entertainment, informativeness, and irritation. According to this model, advertising value significantly influences attitudes toward advertising. Despite its importance in driving consumer responses, researchers have paid little attention to the notion of advertising value (Ducoffe, 1995; Knopper, 1993). By studying advertising value, we can gain a deeper understanding of how advertising functions, with one of its crucial dimensions being the value it holds for consumers (Ducoffe, 1996).

Entertainment

According to McQuail (1987), research on Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) suggests that entertainment in advertising refers to its potential to fulfill consumers’ needs for diversion, aesthetic enjoyment, escapism, or emotional release. This aspect can lead to a deeper level of engagement from customers and familiarize them with the promoted product or service (Lehmkuhl, 2003). The feeling of enjoyment that viewers experience while watching advertisements plays a crucial role in shaping their overall attitudes toward them (Liu et al., 2012; Shavitt et al., 1998; Xu et al., 2009). Chowdhury et al. (2006) and Ducoffe (1995) also established a significant relationship between the entertainment value of advertising and the perceived value of traditional advertising. It is likely that consumers respond positively to an entertaining advertisement (Liu et al., 2012). Thus, it is hypothesized:

H1: Entertainment positively affects the perceived advertising value of video advertisements on SNSs.

Informativeness

Ducoffe (1996) defines “informativeness” as the level of awareness consumers feel regarding the product or service being advertised. When assessing advertising, the significance of informativeness becomes evident through advertising-attitude research. According to Brown and Stayman (1992), informativeness/effectiveness is the most crucial factor in determining brand attitude. Positive responses from recipients to advertising indicate that information holds considerable value as an incentive in marketing (Aitken et al., 2008). When consumers receive details about new products, comparative product information, and specific product benefits, they perceive the information as a favorable aspect of advertising (Shavitt et al., 1998). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H2: Informativeness positively affects the perceived advertising value of video advertisements on SNSs.

Credibility

The term “advertising credibility” pertains to how consumers perceive the truthfulness and believability of advertising in general (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989). Pavlou and Stewart (2000) have defined credibility as the consumer’s belief in the advertising message, assessing the level of trust that customers place in a claim made in an advertisement. Advertising credibility encompasses the perceived believability, truthfulness, and honesty of the advertisement’s content (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989). Additionally, it plays a significant role in determining the level of consumer trust in the claims made in an advertisement (Trivedi et al., 2020).

Research suggests that advertising credibility has a direct positive impact on customer evaluation (Choi & Rifon, 2002; Choi et al., 2008; Tsang et al., 2004). Based on the existing literature, it can be hypothesized that credibility is positively associated with the advertising value perception. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

H3: Credibility positively affects the perceived advertising value of video advertisements on SNSs.

Irritation

In Ducoffe’s (1995, 1996) advertising value model, informativeness and entertainment variables are considered positive predictors, while irritation is viewed as a negative indicator. Brehm (1966) suggests that viewers are less likely to be influenced by advertisements that come across as manipulative, annoying, or offensive. Consumers’ annoyance with advertising can stem from the content of the ads or the overall volume of advertising clutter (Greyser, 1973). Advertisement irritability occurs when consumers feel uncomfortable or bothered by commercials for various reasons. This irritation can manifest in different ways, such as feeling insulted, receiving bothersome messages, or being exposed to other irritating stimuli (Bracket & Carr, 2001).

According to Ducoffe’s model, there is no positive link between the level of irritation and advertising effectiveness. Irritation can arise from several factors, including perceptions of deception, clutter, offensiveness, and misleading information, among others. Even with government and industry regulations in place to protect consumers, some advertising may still be seen as dishonest and deceitful, leading to a diminished perception of advertising’s value. Contrary to the belief that irritating advertising might be more effective, Ducoffe’s model suggests that there is a direct correlation between how irritating an advertisement is and its effectiveness. Thus, the below hypothesis:

H4: Irritation is negatively associated with the perceived advertising value of video advertisements on SNSs.

Personalization

Customers show a greater inclination to reconsider commercials if those advertisements are personalized and align with their lifestyle (DeZoysa, 2002). Consequently, according to Rao and Minakakis (2003), advertisements should take into account the customers’ needs, consumption trends, and preferences. Customers prefer personalized advertising messages that cater to their interests (Milne & Gordon, 1993; Robins, 2003). Furthermore, Xu (2006) discovered that personalized advertising, which targets specific customers based on their interests and purchasing behaviors, can lead to favorable responses and outcomes, particularly in reaching potential customers. Personalization is considered a crucial factor in understanding individual preferences (Al Khasawneh & Shuhaiber, 2013; Kim & Han, 2014; Lee, 2010; Xu, 2006). Based on these findings, the hypothesis is as follows:

H5: Personalization positively affects the perceived advertising value of video advertisements on SNSs.

Interrelationship Between Variables

It is evident from the extant literature that the variables are interrelated with each other.

Advertising Value Perception with Attitude Toward Brand and Attitude Toward Advertising

The primary objectives of advertising are sales and product/service branding (Laudon & Traver, 2013). Branding involves creating a distinct identity for a product or service, and people form opinions about a brand based on the positive and negative messages conveyed through its trademarks (Lee et al., 2017). Advertisements aim to influence consumers’ thoughts, evoke emotions, and temporarily alter their emotional states (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989). Previous research has shown that these cognitive changes are how advertising value influences attitudes toward advertising (Haghirian & Inoue, 2007; Xu et al., 2009). Additionally, since branding is one of the primary objectives of advertising, these cognitive changes also impact brand attitudes, in addition to attitudes toward advertising. In other words, high advertising value positively influences consumers’ perceptions of the brand associated with the product or service.

According to Ducoffe (1995), advertising value perception is a measure of advertising effectiveness that “may indicate customer satisfaction with an organization’s communication efforts.” Attitude toward advertising refers to the inclination to react favorably or unfavorably toward advertising (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989). Exchange is a central concept in marketing, involving the exchange of value between parties (Houston & Gassenheimer, 1987). An advertising communication can serve as a potential channel of communication between a consumer and an advertiser (Ducoffe, 1995). For successful exchanges, the perspectives of both parties need to be considered. A successful exchange can be considered when the advertising value meets consumers’ expectations (Liu et al., 2012). Mayer (1991) observed that technological advancements in communications lead consumers to pay for advertising they prefer and ignore the rest. Based on these considerations, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H6: Advertising value perception positively impacts brand attitudes toward video advertisements on SNSs.

H7: Advertising value perception positively impacts advertising attitudes toward video advertisements on SNSs.

Advertising Attitude and Brand Attitude

The attitude toward advertising plays a crucial role in determining both purchase intention and brand attitude (MacKenzie et al., 1986). Additionally, advertising attitude and brand attitude are interrelated factors, with one influencing the other and jointly impacting purchase intention (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989). Mittal (1990) discovered a positive association between advertising attitude and brand attitude. Various studies examining the factors that influence brand attitude have consistently found advertising attitude to be a significant contributing factor (Aaker & Jacobson, 2001; Han, 1989; Li et al., 2002; MacKenzie & Spreng, 1992).

H8: Attitude toward advertising positively impacts brand attitude on SNSs.

Attitudes and Brand Love

According to Simons (1976), attitude can be defined as a relatively stable inclination to respond positively or negatively toward something. Fishbein (1963) proposed that attitude is the sum of the expected outcomes, weighted by an assessment of how desirable those outcomes are. The theory of planned behavior supports the idea that attitudes influence behavior. Ajzen (1980) found that thoughts that do not readily come to mind during elicitation are less likely to impact behavior. Additionally, Batra et al. (2012) suggest that brand love is closely connected to the strength of an attitude. Based on these arguments, it can be inferred that attitudes toward advertisements and attitudes toward the brand are precursors to brand love. Consequently, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H9: Advertising attitude positively impacts brand love on SNSs.

H10: Brand attitude positively impacts brand love on SNSs.

Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention

According to Miniard et al. (1983), “purchase intention acts as a mediating psychological factor between attitude and actual behavior.” Research indicates that a consumer’s positive perception of a brand significantly influences their intention to purchase and their willingness to pay a premium price (Keller & Lehmann, 2006). Wu and Wang (2011) also consider brand attitude as a predictor of behavioral intentions. Given that brand attitude is the most influential predictor of purchase intention, a customer’s attitude toward a brand has a significant impact on their intention to make a purchase (Abzari et al., 2014). The Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA) supports these findings, as Summers et al. (2006) discovered that attitude toward engaging in a specific behavior is a key determinant of purchase intention. The study further revealed that if a respondent holds a positive attitude about the behavior, they are more likely to make a purchase (Summers et al., 2006). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H11: Brand attitude positively impacts purchase intention on SNSs.

Attitude and eWOM

Brand attitude has been a crucial area of marketing research for many years. Moreover, previous research shows that brand attitude is the most important driver of customer-based brand equity (Ansary & Nik Hashim, 2018; Lane & Jacobson, 1995; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Park et al., 2010; Zarantonello & Schmitt, 2013).

Augusto and Torres (2018) suggest that, when assessing advertising messages, their impact on brand attitude is a common consideration. The formation of customers’ brand attitudes is influenced by their interactions with the brand, either through direct engagement or exposure to marketing materials (Keller, 1993). Additionally, eWOM has been found to play a role in shaping brand attitudes. Research indicates that a favorable brand attitude often results in positive eWOM (Chang et al., 2013; Chu & Sung, 2015). Further, it is hypothesized:

H12: Brand attitude has a positive impact on eWOM on SNSs.

H13: Attitude toward advertising has a positive impact on eWOM on SNSs.

Attitude Toward Advertising and Purchase Intention

Earlier research has indicated a positive connection between individuals’ attitudes toward advertising and their intention to make a purchase (Xu et al., 2009). According to Lee et al. (2017), it is believed that consumers’ attitudes toward advertising, particularly in the context of mobile adverts, can have a positive impact on their purchase intentions. This association is also likely to hold true for SNSs, although there is limited literature available on this particular relationship. Moreover, it is hypothesized:

H14: Attitude toward advertising positively affects purchase intention on SNSs.

Brand Love and Purchase Intention

Researchers have identified various outcomes associated with brand love, such as eWOM recommendations, brand loyalty, purchase intentions, and a willingness to pay a premium (Roberts, 2006; Roy et al., 2013). However, as brand love is a relatively recent concept, further investigation is needed to fully understand its role in establishing a strong consumer-brand relationship (Roy et al., 2013). Additionally, more research is required to explore new factors that contribute to brand love and to verify existing ones in different contexts (Albert & Merunka, 2013; Fetscherin, 2014; Kim & Kim, 2018). The following is hypothesized:

H15: Brand love positively impacts purchase intention on SNSs.

Brand Love and eWOM

According to Carroll and Ahuvia (2006), brand love is associated with desirable post-purchase behaviors such as loyalty and positive word-of-mouth, underscoring its importance in establishing an emotional connection with customers. Consequently, companies seek to foster emotional bonds with their customers to encourage them to speak favorably about the brands they admire (Rageh Ismail & Spinelli, 2012). This emotional connection, as suggested by Rageh Ismail and Spinelli (2012), leads to positive word-of-mouth, wherein customers emotionally express their relationship with the brand. Sarkar (2011) further argues that when customers have strong emotional attachments to a brand, they are more likely to share their positive experiences with others, thus enhancing the brand’s market reach.

Prior research has consistently found a positive correlation between brand loyalty and positive word-of-mouth. When customers have a genuine affection for a brand, they tend to speak highly of it and actively promote it to friends and family (Batra et al., 2012; Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006). In essence, consumers who have a deep connection with a brand become influential advocates for that brand (Dick & Basu, 1994; Harrison-Walker, 2001; .png) lter et al., 2016). They not only recommend the brand to others but also encourage them to make purchases (Correia Loureiro & Kaufmann, 2012). Thus, the hypothesis is as follows:

lter et al., 2016). They not only recommend the brand to others but also encourage them to make purchases (Correia Loureiro & Kaufmann, 2012). Thus, the hypothesis is as follows:

H16: Brand love positively impacts eWOM on SNSs.

Research Methodology

Participants and Procedure

In this research, a descriptive research design was used. The survey was conducted using non-probability snowball sampling, targeting individuals born after 1980 (Generation Y). According to Chapekar (2017), Generation Y, also known as millennials, constitutes the largest portion of viewer traffic on YouTube. They are also the generation most interested in following brands online for information and entertainment. Moreover, millennials are twice as likely as Generation X and Baby Boomers to engage with brands through social media rather than traditional methods like phone calls or emails.

To ensure the confidentiality of responses and overcome non-response bias, respondents were assured that their answers would be kept confidential and used only for study purposes. Data were collected through the survey method from major urban cities in India, considering the easy and affordable access to the internet and smartphones for respondents in these areas. Online forms were circulated for the purpose of data collection. The total responses consisted of 356 responses. After undergoing scrutiny and checks for duplication, it was found that only 328 responses were fit for the study. Out of 328 participants, 59% were female and 41% were male. The average age of the respondents was 31 years.

Measures and Tools

For this study, data collection utilized a structured questionnaire with closed-ended questions, following the approach described by Oppenheim (1992). Drawing insights from the literature, a questionnaire was developed to assess the theory under investigation. It served as a means to gather pertinent data and demographic information from the participants. To ensure clarity and comprehension, the questionnaire was designed in the English language. The study employed existing literature to derive the scales used in the research. These scales were measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (indicating strongly disagree) to 7 (indicating strongly agree). The study measured informativeness and entertainment dimensions with three and four items, respectively, both of which were originally developed by Ducoffe (1995) and Pollay and Mittal (1993). Credibility was measured using a three-item scale adapted from MacKenzie and Lutz’s work (1989). Irritation was measured using the scale introduced by Ducoffe (1995). Personalization was assessed using a three-item scale adopted from Lane and Manner (2011) and Liao (2012). Advertising value perception was studied using a three-item scale taken from Ducoffe’s (1995) work. Although initially designed for traditional advertising media, this scale has been widely used in various studies, including Web 1.0-based media, as seen in the research conducted by Ducoffe (1996) and Wang and Sun (2010). To measure purchase intention, a four-item scale was adopted from Yoo and Donthu (2001). Attitude toward the brand was measured using adoption scales from Lee et al. (2017). Attitude toward advertising was assessed using three items from Zhang and Yuan (2018) and Chowdhury et al. (2006). Furthermore, the scales to measure brand love were derived from the study conducted by Trivedi and Sama (2020). Finally, eWOM scales were adopted from the work of Trivedi and Sama (2020), as well.

Data analysis was done using structural equation modeling (SEM) on Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) software.

Results

After the data were collected, it was checked for missing values. The data were cleaned and deemed fit for further analysis.

Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha values were calculated to determine the reliability of the scales that were employed. All of the variables that were examined had an acceptable value of over 0.7, according to Nunnally (1978). Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s test for sphericity were used to determine the necessity of factor analysis. The significance of the study was demonstrated by the values of 0.946 for the KMO measure and a p value of .000 obtained from Bartlett’s test. Adequacy of the data was indicated by a KMO value falling between 0.8 and 1. The significant result from Bartlett’s test suggested that there were equal variances across the sample populations, and factor loadings above 0.6 were considered acceptable. To detect multicollinearity among variables, the researchers observed the variance inflation factor values. However, the maximum variance inflation factor value of 5.21 indicated the absence of multicollinearity.

Common Method Bias (CMB)

In this study, data were exclusively gathered using a structured questionnaire. As a result, it was crucial to examine whether CMB existed in the data. To address this concern, CMB is checked using Harman’s single-factor test in SPSS. One common factor explained 45.207% of the variance, the value of which is less than 50%. This confirmed that the results were free from CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2003).

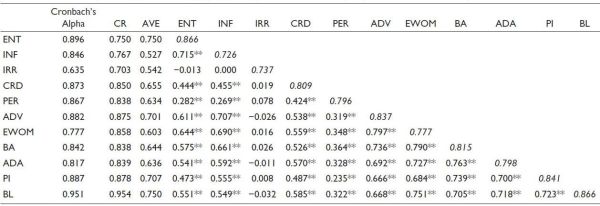

Measurement Model

The measurement model employs latent variables and their indicators to assess the accuracy of measuring the unobserved variables. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to evaluate the overall fit of the model and test the factor loadings. CFA can be applied to multiple constructs or factors simultaneously to ensure the reliability of the measurements concerning the researcher’s conceptualization of these constructs or factors. Additionally, CFA examines the data fit of a hypothesized measurement model that is built on theoretical grounds and previous analytical research. Maximum likelihood estimation was used for CFA, and the model showed an acceptable fit. The recommended fit indices were chi-square (χ2) = 1,524.170, degrees of freedom (df) = 611, p value = .000, CMIN/df = 2.495, GFI = 0.849, AGFI = 0.817, NFI = 0.893, IFI = 0.933, CFI = 0.933, RMSEA = 0.057, and P close = 0.01, were significant and within acceptable limits (Hair et al., 2009). The model is recursive. Further, we have examined the convergent and discriminant validity. The average variance extracted (AVE) and composite reliability (CR) values obtained were both above 0.5 and 0.7, respectively, and were therefore adequate.

Structural Model

Following the validity and reliability assessments as shown in Table 1, the study proceeded to examine the relationship between exogenous and endogenous latent variables. These tests were conducted within the structural model framework (Hair et al., 2010). Unlike CFA, in SEM, it was important to distinguish between independent and dependent variables. In SEM, the causal relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable is represented by a single arrow. Furthermore, SEM assumes covariances between independent variables, which are depicted by two-sided arrows. Consequently, upon transitioning from the measurement model to the structural model, the relationships between the constructs were established. The obtained values of the recommended fit indices were chi-square χ2 = 2,528.298, degrees of freedom (df ) = 683, CMIN/df = 3.702, CFI = 0.917, GFI = 0.855, AGFI = 0.834, TLI = 0.910, NFI = 0.890, RMSEA = 0.59, and P close = 0.00. The results confirmed a good fit between the data and the model.

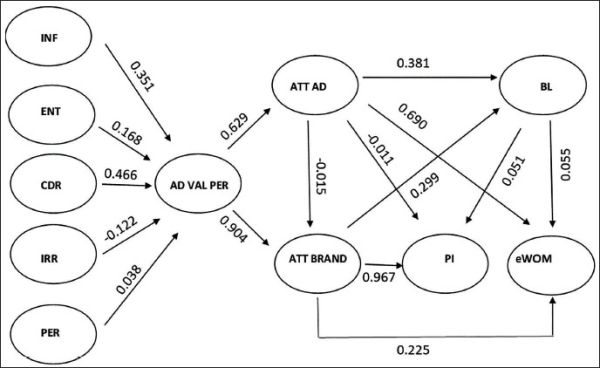

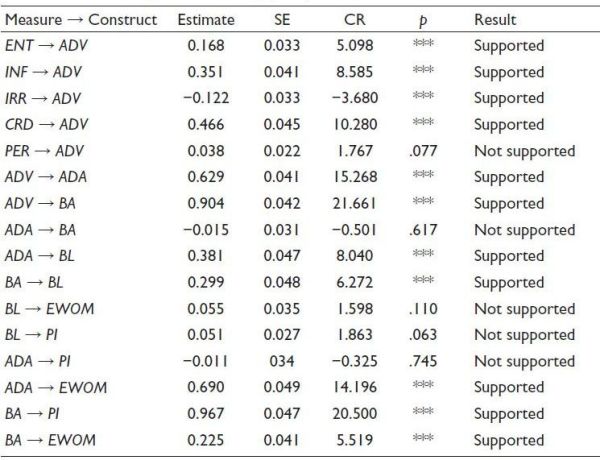

It was found that entertainment (β = 0.168, p < .1), informativeness (β = 0.351, p < .1), and credibility (β = 0.466, p < .1) positively affect advertising value perception, while irritation (β = -0.122, p < .1) negatively impacts advertising value perception. Further, it was confirmed that personalization (β = 0.038, p = .077) does not affect advertising value perception. The results confirmed that advertising value perception positively affects brand attitude (β = 0.904, p < .1) and attitude toward advertising (β = 0.629, p < .1). It is clear from the results that attitude toward advertising does not impact brand attitude (β = -0.015, p = .617). Next, advertising attitude positively impacts brand love (β = 0.381, p < .1) and brand attitude positively impacts brand love (β = 0.299, p < .05). Further, it was found that brand attitude positively impacts purchase intention (β = 0.967, p < .1). Brand attitude has a positive impact on eWOM (β = 0.225, p < .1). Further, advertising attitude has a positive impact on eWOM (β = 0.690, p < .1). It was found that attitude toward advertising does not affect purchase intention (β = -0.011, p = .745). Also, brand love significantly does not affect purchase intention (β = 0.051, p = .063) and eWOM (β = 0.055, p = .110). Figure 1 establishes the relationship between variables, and Table 2 shows if the hypotheses were supported.

Figure 1. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Result.

Discussion and Implications

It is a known fact that brands strive for a positive attitude. Advertising value perception is one of the key factors in creating a positive attitude toward brands as well as the advertising communications of brands. There are several variables that impact advertising value perception. Entertainment is among the strongest determinants of value perception (Karamchandani et al., 2021). Audience experience and aesthetic enjoyment from watching entertaining advertisements (McQuail, 2005). The results of this study are in accordance with several studies on value perception (Ducoffe, 1995, 1996; Karamchandani et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2012; Xu et al., 2009). Further, the inability of advertising to provide information does not woo the viewers. Various studies have supported this claim (Brackett & Carr, 2001; Ducoffe, 1996; Logan et al., 2012; Wang & Sun, 2010). However, the results are in contradiction with the conclusions of Haghirian and Inoue (2007). It was evident from the results that informativeness is an important variable that affects advertising value perception. Also, this study suggests that credibility is the strongest antecedent affecting advertising value perception (β = 0.466). The believability aspect of advertising is considered as credibility, according to Pavlou and Stewart (2000). The claims by brands in advertising are perceived to be of utmost importance to the audience. False and misleading advertisements are not accepted by the viewers, and they tend to lose trust in the brand, which further leads to negative value perception. It is confirmed that irritation is a negative variable that affects advertising value perception. If an advertisement is perceived as offensive, annoying, or manipulative, it is less likely to impact consumers (Brehm, 1966). It is confirmed in this study that irritation negatively impacts advertising value perception. In the context of SNSs, consumers tend to skip ads in order to avoid unwanted promotions. There are instances where viewers pay for blocking ads on SNSs. Advertising clutter, as well as the content of advertisements, can cause irritation (Greyser, 1973). The results of this research are in consideration by several articles (Ducoffe, 1995, 1996; Logan et al., 2012; Saxena & Khanna, 2013). The results of Liu et al. (2012) contradict the findings of this study. However, it is evident in the current study that personalization is not a very essential factor in shaping the advertising value perception. Other factors like entertainment, informativeness, and credibility are more essential in forming a perception toward advertisement.

Table 1. Cronbach’s Alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and Discriminant Validity.

Notes: **Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

ADA: Attitude toward advertising; ADV: Advertising value perception; BA: Brand attitude; BL: Brand love; CRD: Credibility; ENT: Entertainment; EWOM: Electronic word-of-mouth; INF: Informativeness; IRR: Irritation; PER: Personalization; PI: Purchase intention. Italic values show the square root of AVE. A construct should share more variance with its own indicators than with other constructs.

Table 2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Result.

Notes: ***p < .1.

ADA: Attitude toward advertising; ADV: Advertising value perception; BA: Brand attitude; BL: Brand love; CR: Composite reliability; CRD: Credibility; ENT: Entertainment; EWOM: Electronic word-of-mouth; INF: Informativeness; IRR: Irritation; PER: Personalization; PI: Purchase intention.

On further analysis, it was found that advertising, being a source of communication, can lead to positive or negative attitudes. As per MacKenzie and Lutz (1989), advertising messages are capable of inducing cognitive changes in consumers’ minds. Further, Lee et al. (2017) concluded that brand attitude can be altered by cognitive changes. It is clear from the results derived from this study that advertising value perception plays a vital role in forming attitudes toward the brand. Advertising value is an important antecedent to advertising attitude. The intrinsic worth derived through emotional and cognitive assessments influences attitudes (Perloff, 1993). According to MacKenzie and Lutz (1989), the way of responding to ads in an unfavorable or favorable manner is referred to as attitude toward advertising. This research proves that advertising attitude does not impact brand attitude significantly (β = -0.015). A plausible reason for the same is that both attitudes are independent of each other and depend on advertising value perception. It would not be logical to say that one attitude will impact the other. Moreover, brand attitude and advertising attitude are cause and effect factors influencing purchase intention (MacKenzie & Lutz, 1989).

It is known from the literature that brand love is a holistic construct that is recently getting traction in research and that it has emerged as a useful construct (Bergkvist & Bech-Larsen, 2010; Junaid & Hussain, 2016; Rauschnabel & Ahuvia, 2014; Roy et al., 2013). It was therefore taken into consideration in this study. Carroll and Ahuvia (2006) conceptualized brand love. A positive attitude toward advertising leads to brand love. Not many studies have implied this relationship; however, it is evident that attitudes can lead to brand love. Advertising is meant to make viewers engaged, which is the ultimate goal of brand love (Batra et al., 2012). According to Trivedi and Sama (2020), numerous studies have supported the notion that brand attitude is an antecedent to brand love (Albert & Merunka, 2013; Batra et al., 2012; Sarkar & Sarkar, 2016; Trivedi, 2019). The present study is in line with the literature. The relationship between brand attitude and brand love is strongly established (β = 0.299).

Literature suggests that various studies have shown that the relationship between brand attitude and purchase intention exists (Ferreira & Barbosa, 2017; Karamchandani et al., 2021; Kim & Han, 2014; MacKenzie & Spreng, 1992). The results are in line with the literature. The result of this study implies that if the consumer responds positively toward the brand, it is more likely that they will purchase the product from the brand. There are important implications behind studying this relationship. First, purchase intention is considered the end goal of advertising in various studies. The aim of a brand is to sell its products through advertising. Advertising on SNSs makes it even easier to sell a product being advertised. Consumers can buy a product in a single click. Second, negative brand attitude can have its own consequences. It was evident from the results that a negative brand attitude not only results in “no intention to buy” but also in negative word of mouth. Further, the relationship between brand attitude and eWOM is discussed. Positive or negative attitudes toward the brand can lead to word of mouth by consumers on SNSs. The current study statistically confirms the relationship between brand attitude and eWOM. The result is in line with some studies (Chang et al., 2013; Chu & Sung, 2015). Furthermore, as per Mangold and Faulds (2009), social media is home to several WOM forums, ranging from blogs to rating websites and company-sponsored discussion boards. All this enables the consumers to comment on SNSs platforms, like Instagram, YouTube, and Facebook. Advertising on these platforms influences consumers’ attitudes, which in turn encourages them to engage in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM). Not many studies have considered this relationship in the literature. However, this study paves the path to explore this relationship in depth. Statistical test results have shown a strong relationship between advertising attitude and eWOM, which is even stronger than the widely accepted relationship between brand attitude and eWOM.

Attitude toward advertising is descended from advertising value perception. Several studies have found that advertising value perception does not impact purchase intention (Karamchandani et al., 2021). This fact was contradictory to several studies (Martins et al., 2019; Van-Tien Dao et al., 2014). Therefore, the need arises to find out if attitude toward advertising affects purchase intention. However, the study strongly suggests that attitude toward advertising is not related to purchase intention. It can be said that even if a consumer has a positive attitude toward an advertisement, it does not ensure that they will purchase the product being advertised. Further, extant literature suggests that there is a favorable association between satisfaction and willingness to buy that brand (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993), and the effect of brand loyalty on the intention to purchase (Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978; Srinivasan et al., 2002). But surprisingly, this study disagrees with the claim that brand love affects purchase intention (β = 0.051). A plausible explanation for the same could be the lack of buying capacity for the brand in spite of the desire to use that brand. Mittal (2006) concluded that consumers seek brands in accordance with their own personality, values, and lifestyle. A customer might love a brand and aspire to buy the brand; however, other factors might make the purchase intention unfavorable. One plausible explanation could be that a customer might love the brand; however, other factors, such as a high price, could lead to a negative purchase intention. Another reason could be the availability of the product. SNSs advertising can be viewed by consumers globally.

Brand love and eWOM are higher-order constructs (also known as hierarchical component models in the context of SEM, as per Lohmöller (1989). Higher-order constructs are based on more abstract dimensions. Bairrada et al. (2018) suggested that brand love impacts WOM. The result of the present study contradicts with this. Various studies suggest that brand love results in positive consumer responses (Rodrigues & Rodrigues, 2019; Trivedi, 2020). Surprisingly, it is not the case for SNSs advertisements.

Limitations and Scope

Like any scientific investigation, this study is not exempt from limitations. First, it focuses solely on the geographical region, India, which, despite having a large number of SNS users, may not provide a complete understanding of the variables’ impact on advertising value perception due to the use of cross-sectional data. To overcome this limitation, a longitudinal study could be conducted to validate the obtained results. Additionally, the study’s scope is limited to millennials due to time and budget constraints. Expanding the investigation to include other age groups would offer a better grasp of purchase intention across different demographics. Moreover, the study does not account for the various formats of eWOM available on SNSs, such as videos, images, and text reviews. Future research could explore sentiment analysis through eWOM and investigate the effects of negative eWOM on purchase intention. Furthermore, with the continuous evolution of SNSs, video advertising now comes in various formats, including “reels” on Instagram. A comparative study between different video advertising formats could be pursued in future research. Despite these limitations, the study presents a comprehensive model of advertising value perception, which could be tested for various advertising media and formats. This allows for the possibility of refining the model and gaining a deeper understanding of advertising perception across different platforms.

Conclusion

The study has successfully achieved its research objectives and effectively confirmed the hypothesized relationships. Furthermore, its contribution is not limited to academia alone; it also serves to bridge the gap between industry and academia. The research carries significant theoretical and practical implications, offering valuable insights for advertisers and brand managers. By implementing the findings, they can enhance advertising value perception, ultimately leading to greater viewer engagement with their ads. Additionally, the model proposed in this research can be employed to measure purchase intention, aiding in sales improvement. Moreover, the study delves into the emotional aspects of branding, shedding light on brand love toward the brand.

The model used in this research establishes important relationships, thereby contributing substantially to the existing knowledge within the marketing field. The intriguing results and the disruptive nature of video advertising on SNSs have sparked curiosity and enthusiasm for further investigation. The researchers predict that new and captivating discoveries await in this area of research.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Shikha Karamchandani  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2042-1665

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2042-1665

Mitesh Jayswal  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7188-8380

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7188-8380

Aaker, D. A., & Jacobson, R. (2001). The value relevance of brand attitude in high-technology markets. Sage Publications.

Abzari, M., Ghassemi, R. A., & Vosta, L. N. (2014). Analysing the effect of social media on brand attitude and purchase intention: The case of Iran Khodro Company. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 143, 822–826.

Aitken, R., Gray, B., & Lawson, R. (2008). Advertising effectiveness from a consumer perspective. International Journal of Advertising, 27(2), 279–297.

Ajzen, I. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predictiing social behavior. Prentice-Hall.

Albert, N., & Merunka, D. (2013). The role of brand love in consumer-brand relationships. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(3), 258–266.

Al Khasawneh, M., & Shuhaiber, A. (2013). A comprehensive model of factors influencing consumer attitude towards and acceptance of SMS advertising: An empirical investigation in Jordan. International Journal of Sales & Marketing Management Research and Development, 3(2), 1–22.

Ansary, A., & Nik Hashim, N. M. H. (2018). Brand image and equity: The mediating role of brand equity drivers and moderating effects of product type and word of mouth. Review of Managerial Science, 12, 969–1002.

Augusto, M., & Torres, P. (2018). Effects of brand attitude and eWOM on consumers’ willingness to pay in the banking industry: Mediating role of consumer-brand identification and brand equity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 42, 1–10.

Bairrada, C. M., Coelho, F., & Coelho, A. (2018). Antecedents and outcomes of brand love: Utilitarian and symbolic brand qualities. European Journal of Marketing, 52(3–4), 656–682.

Batra, R., Ahuvia, A., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2012). Brand love. Journal of Marketing, 76(2), 1–16.

Bergkvist, L., & Bech-Larsen, T. (2010). Two studies of consequences and actionable antecedents of brand love. Journal of Brand Management, 17, 504–518.

Berthon, P., Pittb, L., & Watson, R. T. (1996). Re-surfing W3: Research perspectives on marketing communication and buyer behaviour on the worldwide web. International Journal of Advertising, 15(4), 287–301.

Brackett, L. K., & Carr, B. N. (2001). Cyberspace advertising vs. other media: Consumer vs. mature student attitudes. Journal of Advertising Research, 41(5), 23–32.

Brake, S. V., & Safko, L. (2009). The social media Bible: Tactics, tools, and strategies for business success (p. 45). John Wiley & Sons Incorporated.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

Brown, J., Broderick, A. J., & Lee, N. (2007). Word of mouth communication within online communities: Conceptualizing the online social network. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21(3), 2–20.

Brown, S. P., & Stayman, D. M. (1992). Antecedents and consequences of attitude toward the ad: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(1), 34–51.

Carroll, B. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters, 17(2), 79–89.

Chang, A., Hsieh, S. H., & Tseng, T. H. (2013). Online brand community response to negative brand events: The role of group eWOM. Internet Research, 23(4), 486–506.

Chapekar, A. (2017). What kind of videos do people from different age groups consume? http://www.toolbox-studio.com/blog/videos-people-from-different-age-groupsconsumers

Choi, Y. K., Hwang, J., & McMillan, S. J. (2008). Gearing up for mobile advertising: A cross-cultural examination of key factors that drive mobile messages home to consumers. Psychology & Marketing, 25(8), 756–768.

Choi, S. M., & Rifon, N. J. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of web advertising credibility: A study of consumer response to banner ads. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 3(1), 12–24.

Chowdhury, H. K., Parvin, N., Weitenberner, C., & Becker, M. (2006). Consumer attitude toward mobile advertising in an emerging market: An empirical study. International Journal of Mobile Marketing, 1(2), 33–41.

Chu, S.-C., & Sung, Y. (2015). Using a consumer socialization framework to understand electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) group membership among brand followers on Twitter. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 14(4), 251–260.

Correia Loureiro, S. M., & Kaufmann, H. R. (2012). Explaining love of wine brands. Journal of Promotion Management, 18(3), 329–343.

DeZoysa, S. (2002). Mobile advertising needs to get personal. Telecommunications International, 36(2), 8.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22, 99–113.

Ducoffe, R. H. (1995). How consumers assess the value of advertising. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.1995.10505022

Ducoffe, R. H. (1996). Advertising value and advertising on the web-Blog@ management. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(5), 21–32.

Eagly, A. H., & Chaiken, S. (1993). The psychology of attitudes. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers.

Ferreira, F., & Barbosa, B. (2017). Consumers’ attitude toward Facebook advertising. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 8(1), 45–57.

Fetscherin, M. (2014). What type of relationship do we have with loved brands? Journal of Consumer Marketing, 31(6/7), 430–440.

Fishbein, M. (1963). An investigation of the relationships between beliefs about an object and the attitude toward that object. Human Relations, 16(3), 233–239.

Greyser, S. A. (1973). Irritation in advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 13(1), 3–10.

Haghirian, P., & Inoue, A. (2007). An advanced model of consumer attitudes toward advertising on the mobile internet. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 5(1), 48–67.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados. Bookman Editora.

Hair, J. F., Ortinau, D. J., & Harrison, D. E. (2010). Essentials of marketing research (Vol. 2). McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Han, C. M. (1989). Country image: Halo or summary construct? Journal of Marketing Research, 26(2), 222–229.

Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2001). The measurement of word-of-mouth communication and an investigation of service quality and customer commitment as potential antecedents. Journal of Service Research, 4(1), 60–75.

Houston, F. S., & Gassenheimer, J. B. (1987). Marketing and exchange. Journal of Marketing, 51(4), 3–18.

.png) lter, B., B

lter, B., B.png) çakc

çakc.png) o

o.png) lu, N., & Yaran,

lu, N., & Yaran, .png) . Ö. (2016). How brand jealousy influences the relationship between brand attachment and word of mouth communication. Acta Universitatis Danubius Communicatio, 10(1), 109–125.

. Ö. (2016). How brand jealousy influences the relationship between brand attachment and word of mouth communication. Acta Universitatis Danubius Communicatio, 10(1), 109–125.

Jacoby, J., & Chestnut, R. W. (1978). Brand loyalty: Measurement and management. John Wiley & Sons Incorporated.

Junaid, M., & Hussain, K. (2016). Impact of brand personality, perceived quality and perceived value on brand love; Moderating role of emotional stability. Middle East Journal of Management, 3(4), 278–293.

Kaplan, A. M., & Haenlein, M. (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Business Horizons, 53(1), 59–68.

Karamchandani, S., Karani, A., & Jayswal, M. (2021). Linkages between advertising value perception, context awareness value, brand attitude and purchase intention of hygiene products during COVID-19: A two wave study. Vision, 28. https://doi.org/10.1177/09722629211043954

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22.

Keller, K. L., & Lehmann, D. R. (2006). Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Marketing Science, 25(6), 740–759.

Kim, Y. J., & Han, J. (2014). Why smartphone advertising attracts customers: A model of Web advertising, flow, and personalization. Computers in Human Behavior, 33, 256–269.

Kim, M.-S., & Kim, J. (2018). Linking marketing mix elements to passion-driven behavior toward a brand: Evidence from the foodservice industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(10), 3040–3058.

Knopper, D. (1993). How about adding value to the advertising message. Advertising Age, 12(18), l.

Lane, V., & Jacobson, R. (1995). Stock market reactions to brand extension announcements: The effects of brand attitude and familiarity. Journal of Marketing, 59(1), 63–77.

Lane, W., & Manner, C. (2011). The impact of personality traits on smartphone ownership and use. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(17), 22–28.

Laudon, K. C., & Traver, C. G. (2013). E-commerce 2012: Business, technology, society (p. 12). Pearson.

Lee, Y.-C. (2010). Factors influencing attitudes towards mobile location-based advertising. 2010 IEEE international conference on software engineering and service sciences (pp. 709–712). Beijing, China.

Lee, J., & Hong, I. B. (2016). Predicting positive user responses to social media advertising: The roles of emotional appeal, informativeness, and creativity. International Journal of Information Management, 36(3), 360–373.

Lee, E.-B., Lee, S.-G., & Yang, C.-G. (2017). The influences of advertisement attitude and brand attitude on purchase intention of smartphone advertising. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(6), 1011–1036.

Lehmkuhl, F. (2003). Küsse und machotests (p. 6). Focus.

Li, H., Daugherty, T., & Biocca, F. (2002). Impact of 3-D advertising on product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: The mediating role of presence. Journal of Advertising, 31(3), 43–57.

Liao, C.-S. (2012). Self-construal, personalization, user experience, and willingness to use codesign for online games. Information, Communication & Society, 15(9), 1298–1322.

Liu, C.-L., ‘Eunice’,, Sinkovics, R. R., Pezderka, N., & Haghirian, P. (2012). Determinants of consumer perceptions toward mobile advertising—A comparison between Japan and Austria. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(1), 21–32.

Logan, K., Bright, L. F., & Gangadharbatla, H. (2012). Facebook versus television: Advertising value perceptions among females. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 6(3), 164–179.

Lohmöller, J.-B. (1989). Predictive vs. structural modeling: PLS vs. ML. In Latent variable path modeling with partial least squares (pp. 199–226). Heidelberg.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Lutz, R. J. (1989). An empirical examination of the structural antecedents of attitude toward the ad in an advertising pretesting context. Journal of Marketing, 53(2), 48–65.

MacKenzie, S. B., Lutz, R. J., & Belch, G. E. (1986). The role of attitude toward the ad as a mediator of advertising effectiveness: A test of competing explanations. Journal of Marketing Research, 23(2), 130–143.

MacKenzie, S. B., & Spreng, R. A. (1992). How does motivation moderate the impact of central and peripheral processing on brand attitudes and intentions? Journal of Consumer Research, 18(4), 519–529.

Mangold, W. G., & Faulds, D. J. (2009). Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Business Horizons, 52(4), 357–365.

Martins, J., Costa, C., Oliveira, T., Gonçalves, R., & Branco, F. (2019). How smartphone advertising influences consumers’ purchase intention. Journal of Business Research, 94, 378–387.

Mayer, M. (1991). Whatever happened to Madison Avenue? Advertising in the ’90s. Little Brown & Company.

McQuail, D. (1987). Mass communication theory: An introduction. Sage Publications.

McQuail, D. (2005). Communication theory and the Western bias. Language Power and Social Process, 14, 21.

Milne, G. R., & Gordon, M. E. (1993). Direct mail privacy-efficiency trade-offs within an implied social contract framework. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 12(2), 206–215.

Miniard, P. W., Obermiller, C., & Page, T. J., Jr. (1983). A further assessment of measurement influences on the intention-behavior relationship. Journal of Marketing Research, 20(2), 206–212.

Mittal, B. (1990). The relative roles of brand beliefs and attitude toward the ad as mediators of brand attitude: A second look. Journal of Marketing Research, 27(2), 209–219.

Mittal, B. (2006). I, me, and mine—How products become consumers; Extended selves. Journal of Consumer Behaviour: An International Research Review, 5(6), 550–562.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory (2d ed). McGraw-Hill.

Oppenheim, A. N. (1992). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement (New ed.). Pinter Publishers.

Pahari, S., Bandyopadhyay, A., VM, V. K., & Pingle, S. (2024). A bibliometric analysis of digital advertising in social media: the state of the art and future research agenda. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2383794.

Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1–17.

Pavlou, P. A., & Stewart, D. W. (2000). Measuring the effects and effectiveness of interactive advertising: A research agenda. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 1(1), 61–77.

Perloff, R. M. (1993). The dynamics of persuasion: Communication and attitudes in the 21st century. Routledge.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879.

Pollay, R. W., & Mittal, B. (1993). Here’s the beef: Factors, determinants, and segments in consumer criticism of advertising. Journal of Marketing, 57(3), 99–114.

Rageh Ismail, A., & Spinelli, G. (2012). Effects of brand love, personality and image on word of mouth: The case of fashion brands among young consumers. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 16(4), 386–398.

Rao, B., & Minakakis, L. (2003). Evolution of mobile location-based services. Communications of the ACM, 46(12), 61–65.

Rauschnabel, P. A., & Ahuvia, A. C. (2014). You’re so lovable: Anthropomorphism and brand love. Journal of Brand Management, 21, 372–395.

Rizavi, S. S., Ali, L., & Rizavi, S. H. M. (2011). User perceived quality of social networking websites: A study of Lahore region. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 2(12), 902–913.

Roberts, K. (2006). The lovemarks effect: Winning in the consumer revolution. Mountaineers Books.

Robins, F. (2003). The marketing of 3G. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 21(6), 370–378.

Rodrigues, C., & Rodrigues, P. (2019). Brand love matters to millennials: The relevance of mystery, sensuality and intimacy to neo-luxury brands. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 28(7), 830–848.

Roy, S. K., Eshghi, A., & Sarkar, A. (2013). Antecedents and consequences of brand love. Journal of Brand Management, 20(4), 325–332.

Sarkar, A. (2011). Romancing with a brand: A conceptual analysis of romantic consumer-brand relationship. Management & Marketing, 6(1), 79.

Sarkar, A., & Sarkar, J. G. (2016). Devoted to you my love: Brand devotion amongst young consumers in emerging Indian market. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 28(2), 180–197.

Saxena, A., & Khanna, U. (2013). Advertising on social network sites: A structural equation modelling approach. Vision, 17(1), 17–25.

Shavitt, S., Lowrey, P., & Haefner, J. (1998). Public attitudes toward advertising: More favorable than you might think. Journal of Advertising Research, 38(4), 7–22.

Simons, H. W. (1976). Persuasion: Understanding, practice, and analysis (p. 21). Addison-Wesley.

Sprout Social. (2018). #BrandsGetReal: What consumers want from brands in a divided society. https://sproutsocial.com/insights/data/social-media-connection/

Srinivasan, S. S., Anderson, R., & Ponnavolu, K. (2002). Customer loyalty in e-commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 41–50.

Statista. (2024). Number of internet users worldwide from 2005 to 2024. Statista. Retrieved August 12, 2025, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/273018/number-of-internet-users-worldwide/

Summers, T. A., Belleau, B. D., & Xu, Y. (2006). Predicting purchase intention of a controversial luxury apparel product. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 10(4), 405–419.

Taylor, D. G., Lewin, J. E., & Strutton, D. (2011). Friends, fans, and followers: Do ads work on social networks? How gender and age shape receptivity. Journal of Advertising Research, 51(1), 258–275.

Trivedi, J. P., Deshmukh, S., & Kishore, A. (2020). Wooing the consumer in a six-second commercial! Measuring the efficacy of bumper advertisements on YouTube. International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing, 11(3), 307–322.

Trivedi, J. (2019). Examining the customer experience of using banking chatbots and its impact on brand love: the moderating role of perceived risk. Journal of Internet Commerce, 18(1), 91–111.

Trivedi, J., & Sama, R. (2020). The effect of influencer marketing on consumers’ brand admiration and online purchase intentions: An emerging market perspective. Journal of Internet Commerce, 19(1), 103–124.

Tsang, M. M., Ho, S.-C., & Liang, T.-P. (2004). Consumer attitudes toward mobile advertising: An empirical study. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 8(3), 65–78.

Van-Tien Dao, W., Nhat Hanh Le, A., Ming-Sung Cheng, J., & Chao Chen, D. (2014). Social media advertising value: The case of transitional economies in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Advertising, 33(2), 271–294.

Wang, Y., & Sun, S. (2010). Examining the role of beliefs and attitudes in online advertising. International Marketing Review, 27(1), 87–107.

Wu, P. C. S., & Wang, Y. (2011). The influences of electronic word-of-mouth message appeal and message source credibility on brand attitude. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 23(4), 448–472.

Xu, D. J. (2006). The influence of personalization in affecting consumer attitudes toward mobile advertising in China. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 47(2), 9–19.

Xu, H., Oh, L.-B., & Teo, H.-H. (2009). Perceived effectiveness of text vs. multimedia location-based advertising messaging. International Journal of Mobile Communications, 7(2), 154–177.

Yoo, B., & Donthu, N. (2001). Developing a scale to measure the perceived quality of an internet shopping site (SITEQUAL). Quarterly Journal of Electronic Commerce, 2(1), 31–45.

Zarantonello, L., & Schmitt, B. H. (2013). The impact of event marketing on brand equity: The mediating roles of brand experience and brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 32(2), 255–280.

Zhang, X., & Yuan, S.-M. (2018). An eye tracking analysis for video advertising: Relationship between advertisement elements and effectiveness (Vol. 6, pp. 10699–10707). IEEE Access.