1Faculty of Management, JIS University, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

2Department Of Geography and Environmental Sciences, University of Southampton, United Kingdom

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

Urban food environments in developing economies present unique challenges for public health, particularly in the domain of informal street food consumption. This study investigates how integrated marketing strategies—comprising vendor training, digital marketing, hygiene certifications, and education campaigns—influence consumer trust and behavior regarding food safety. Utilizing Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) on data collected from street food consumers in Kolkata, India, the study demonstrates that marketing interventions significantly enhance trust in both certifications and vendor practices, which in turn positively predict safe behavioral intentions. The structural model reveals strong path coefficients and substantial effect sizes, indicating a robust link between marketing strategy, trust formation, and public health outcomes. The findings underscore the need for multi-level health communication strategies that incorporate both institutional and interpersonal trust mechanisms. Practical implications for policymakers and municipal authorities are discussed, with recommendations for integrating vendor training and public awareness into urban food safety frameworks. This research contributes to theory by contextualizing trust as a dual mediator and offers actionable insights for sustainable health promotion in complex urban food systems.

Urban food systems, food safety behavior, trust in food certifications, marketing strategy, health communication, street food safety, consumer behavior, public health intervention

Introduction

The global proliferation of street food vending is a reflection of its socioeconomic and cultural significance, particularly in developing urban centers such as Kolkata. Street food offers an accessible, affordable, and culturally rich source of nutrition to large segments of the population (FAO, 2016). Despite these benefits, the street food sector operates largely within informal regulatory frameworks, where concerns over hygiene, food safety, and consumer protection are pressing public health issues (WHO, 2020). In India, the coexistence of high demand for street food and the risk of foodborne illnesses represents a persistent challenge, requiring innovative and integrated strategies that extend beyond traditional regulatory interventions.

One key area has been the role of strategic marketing and communication initiatives in influencing consumer perceptions and behaviors related to food safety. These strategies include hygiene certification schemes, digital and educational campaigns, and vendor training programs—all aimed at increasing awareness, improving vendor compliance, and reinforcing trust among consumers. Marketing interventions, when designed with public health objectives, can significantly influence behavioral intentions and attitudes toward street food consumption (Choudhury et al., 2011; Sparks et al., 2014). In particular, digital marketing tools, which leverage mobile technology and social media platforms, have demonstrated efficacy in shaping urban consumer behavior in India’s rapidly digitizing landscape (Kapoor & Dwivedi, 2020).

Hygiene certification programs and food safety labels have also been extensively studied for their ability to signal food safety compliance to consumers. Drawing from the cue utilization theory (Olson & Jacoby, 1972), consumers tend to rely on extrinsic cues like hygiene seals and endorsements in making food choices, particularly in high-uncertainty contexts such as street food markets. Certifications offered by local municipalities or third-party food safety organizations can reduce information asymmetry, thereby enhancing consumer confidence in the food’s safety (Ali & Nath, 2013). In the Indian context, initiatives like the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI)’s “Clean Street Food Hub” program reflect efforts to institutionalize such certification schemes (FSSAI, 2021). However, the efficacy of these programs is not uniform and is often mediated by the degree of public trust in the certifying authorities (Yeung & Morris, 2001).

This leads to a crucial mediating construct in this research—trust. Trust plays a dual role: on one hand, it reflects institutional trust in food safety regulators and marketing programs, and on the other, it represents interpersonal trust in individual vendors. The literature identifies trust as a foundational element in risk management and behavior change, particularly in public health domains (Chen, 2013; Frewer et al., 1996). Without trust in the regulatory institutions or in the vendors themselves, consumers are unlikely to respond to marketing efforts aimed at promoting safe food practices. In low- and middle-income countries, where regulatory enforcement is often weak, interpersonal trust developed through repeated vendor–consumer interactions can substitute for formal assurances (Kumar & Kapoor, 2017).

Furthermore, trust serves as a psychological safety net, reducing the perceived risk associated with consuming street food (Lobb et al., 2007). Research shows that trust is positively correlated with favorable attitudes and behavioral intentions in food choices (Han & Hyun, 2017). In the context of hygiene certification, for instance, consumer perceptions of credibility and transparency in the certification process influence the extent to which they internalize and act upon the safety message (Wang et al., 2019). Therefore, any study of marketing efficacy in the informal food sector must account for the pivotal role of trust in mediating behavior.

Consumer behavior itself is central to public health outcomes in the street food economy. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Ajzen, 1991) provides a robust theoretical foundation for predicting food safety behaviors. According to TPB, behavioral intention—defined by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—directly influences actual behavior. In this context, attitudes toward hygiene, peer norms surrounding safe food choices, and an individual’s confidence in avoiding unsafe vendors are all modifiable constructs (Grunert, 2005). Marketing and educational interventions can influence these TPB dimensions by increasing knowledge, reshaping attitudes, and enhancing perceived control over food choices.

Studies such as Liu et al. (2014) and Soon et al. (2012) have demonstrated that awareness and knowledge of food safety are strong predictors of safe food consumption practices. However, gaps remain in empirical understanding of how integrated marketing strategies and trust dynamics jointly influence these behaviors. Most existing studies have either focused on vendor compliance or consumer awareness in isolation. There is a paucity of research that adopts a systems perspective, analyzing how various factors interact to shape health-related consumer behavior within complex urban ecosystems.

Finally, public health outcomes are contingent upon sustained improvements in consumer and vendor behaviors. Foodborne illness in urban India continues to pose a substantial health burden, affecting vulnerable populations including children, the elderly, and the immunocompromised (Barro et al., 2006; WHO, 2020). Behavior changes at the consumer level—facilitated through trust-building and strategic marketing—can contribute to broader community health benefits by reducing exposure to unsafe food sources.

In response to these gaps, the present study proposes a structural model based on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to empirically test the relationships among marketing interventions, trust (both institutional and interpersonal), consumer behavior, and public health outcomes. By situating this study within the context of Kolkata’s diverse street food landscape, the research aims to provide both theoretical advancement and practical guidance for policymakers, health practitioners, and food safety regulators.

Literature Review

Street food vending constitutes a vital component of the informal urban economy in many developing nations , offering affordable meals to low- and middle-income populations. Yet, it poses significant public health risks due to inconsistent safety standards and limited regulatory oversight (FAO, 2016; WHO, 2020). As such, understanding how institutional interventions—particularly marketing strategies—interact with consumer trust and behavior is essential for developing effective, scalable policy frameworks. While several studies have investigated hygiene practices and consumer awareness (Barro et al., 2006; Choudhury et al., 2011), relatively few adopt an integrative perspective linking these factors with behavioral theory and structural modeling approaches.

Marketing Interventions and Consumer Perception

The literature increasingly acknowledges the utility of strategic marketing—including digital campaigns, hygiene certifications, and vendor training—as a vehicle for enhancing food safety awareness. Hygiene certification schemes, in particular, function as quality assurance signals that mitigate consumers’ information asymmetries about food safety (Ali & Nath, 2013; Wang et al., 2019). In India, programs under the aegis of the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI), such as the “Clean Street Food Hub”, aim to institutionalize hygiene awareness through branding and vendor incentives (FSSAI, 2021). However, the impact of these initiatives remains inconsistent, often limited by enforcement challenges and low consumer trust in certification bodies (Kumar & Kapoor, 2017).

Digital marketing, particularly via social media and mobile applications, is emerging as a low-cost method for delivering food safety information. Kapoor and Dwivedi (2020) argue that the digital medium can empower consumers by providing real-time, localized safety information. Yet, adoption among street vendors is uneven, constrained by digital literacy and infrastructural limitations. Furthermore, while digital platforms can increase message reach, their impact on behavioral change is rarely evaluated longitudinally, leaving questions about sustained effectiveness.

Trust as a Mediating Construct

Trust—both in institutions (e.g., government, certifiers) and vendors (e.g., known sellers)—has been identified as a critical variable influencing risk perception and behavioral intent (Frewer et al., 1996; Lobb et al., 2007). Yeung and Morris (2001) argue that without trust, even well-designed interventions may fail to shift consumer behavior. However, the trust construct is often treated superficially in the food safety literature, with limited distinction between interpersonal and institutional dimensions.

Recent empirical work has attempted to disentangle these levels. Han and Hyun (2017) show that trust in foodservice providers is positively correlated with repeat purchase intentions, while Chen (2013) emphasizes that institutional transparency and responsiveness are key to building public confidence. Nonetheless, much of the existing research is situated in high-income countries with mature regulatory environments. Studies in developing contexts, where trust in formal institutions is often low and reliance on interpersonal networks is high, remain sparse and insufficiently theorized (Kumar & Kapoor, 2017).

This omission is problematic, particularly in environments like Kolkata, where street food consumers frequently rely on familiar vendors or community endorsements to assess hygiene (Banik et al., 2021). These trust-based heuristics can either complement or undermine institutional certification programs. Yet few studies systematically examine how these dual dimensions of trust interact or how they may mediate the relationship between institutional marketing strategies and consumer behavior. Street food vending represents a vital, yet underregulated, component of the urban informal economy in many developing countries, serving as both a livelihood source and a primary meal option for low- and middle-income populations. However, its growth has outpaced regulatory oversight, giving rise to public health concerns that are increasingly addressed through institutional marketing interventions, consumer education, and trust-building mechanisms (Majumder et al., 2025).

Consumer Behavior and the Theory of Planned Behavior

Consumer behavior in food safety contexts is frequently modeled using the TPB, which posits that behavior is shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (Ajzen, 1991). Grunert (2005) and Sparks et al. (2014) have applied TPB constructs to food consumption settings, arguing that information-based interventions can positively influence attitudes and norms, particularly when reinforced by trusted sources. However, in informal food economies, consumers often face constrained choice environments where perceived behavioral control is low due to financial or logistical barriers.

Moreover, knowledge of food safety does not always translate to behavior. Liu et al. (2014) and Soon et al. (2012) observe that while food safety awareness has increased, behavioral shifts remain limited, particularly among price-sensitive consumers. This attitude–behavior gap calls into question the assumption that awareness alone is sufficient to drive change. It also highlights the importance of contextual variables, such as trust and perceived accessibility, that moderate TPB pathways.

Crucially, enhancing public education on this emerging concern is essential, given its potential threats to environmental integrity and public health (Majumder & Mukherjee, 2023). Most existing work adopts a piecemeal approach, examining variables in isolation rather than as components of an interactive system. This fragmentation limits the explanatory power of existing models and impedes the development of holistic strategies for food safety governance.

Gaps and Research Imperatives

The critical gap in the literature lies in the absence of integrated, empirical models that assess the causal pathways linking institutional marketing, trust (institutional and interpersonal), consumer behavior, and public health outcomes. While tools such as PLS-SEM have been employed in other public health contexts (Hair et al., 2021), their application to informal food systems remains limited.

Furthermore, there is a notable geographic gap, with most empirical studies focused on Western or East Asian markets. The unique sociocultural and infrastructural conditions of Indian urban food systems, including heterogeneity in vendor training, enforcement capacity, and consumer demographics, warrant localized investigation. The present study addresses this gap by using PLS-SEM to model these constructs within Kolkata’s street food ecosystem, contributing to both theoretical refinement and policy relevance.

Research Methodology

Research Design

This study adopts a quantitative, cross-sectional research design to investigate the relationships between strategic marketing interventions, trust dimensions, consumer behavior, and public health outcomes within Kolkata’s street food ecosystem. The cross-sectional approach allows for the simultaneous examination of multiple constructs at a specific point in time, suitable for exploring behavioral patterns, and latent perceptions within urban populations (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Quantitative methods were deemed appropriate due to the hypothesis-driven nature of the research and the need for empirical validation of a structural model using latent constructs.

Instrument Design and Measurement Model

The research instrument was developed based on established scales adapted to the context of street food safety and consumer behavior. A structured questionnaire comprising multiple-item constructs was used, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree). The instrument was pre-tested for face validity through expert reviews and pilot-tested on a sample of 30 participants to ensure clarity and reliability.

The measurement model included the following constructs:

The questionnaire was subjected to content validity evaluation and confirmed via confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in SmartPLS 4.0 to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement items.

Sample and Data Collection

The study targeted street food consumers and vendors within Kolkata, India, where the street food culture is diverse and widely patronized. A purposive sampling technique was employed to capture respondents who had recent experience with street food consumption or vending. The inclusion criteria included adults (18 years and above) residing in Kolkata and having purchased or sold street food in the past three months.

Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires and structured interviews at major street food hubs across Kolkata, including Gariahat, Esplanade, College Street, and New Market. The final sample comprised 232 valid responses, which exceeds the minimum recommended sample size for SEM using PLS (Hair et al., 2021). Ethical considerations, including informed consent and respondent confidentiality, were strictly maintained.

Data Analysis and Results

The data were analyzed using SmartPLS 4.0, a variance-based SEM tool that supports exploratory and predictive modeling. SmartPLS is suitable for complex models with latent constructs and does not assume multivariate normality, making it appropriate for social science research involving non-probability samples (Sarstedt et al., 2017).

Measurement Model Assessment

The measurement model was assessed for reliability and validity through the following procedures:

.png) 0.70 were considered acceptable, while items loading between 0.40 and 0.70 were retained selectively based on their contribution to construct reliability.

0.70 were considered acceptable, while items loading between 0.40 and 0.70 were retained selectively based on their contribution to construct reliability.The results confirmed that all constructs met the reliability and validity criteria, indicating a robust measurement model.

Structural Model Assessment

The structural model was evaluated using bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples to test the significance of path coefficients. The following criteria were used:

The structural model provided empirical support for the hypothesized relationships between marketing strategies, trust mechanisms, consumer behavior, and public health outcomes. Mediation analysis was also conducted to explore the indirect role of trust between institutional interventions and behavioral outcomes.

Results

The reliability of the indicators was assessed by looking at the outer loadings of each item on its corresponding latent construct. Outer loadings greater than 0.70 are deemed optimal, meaning that the latent construct accounts for more than half of the variance of the indicator (Hair et al., 2021). If AVE values and overall construct reliability are still acceptable, loadings in the range of 0.40–0.70 might be kept. Generally speaking, items with loadings less than 0.40 should be eliminated from the model.

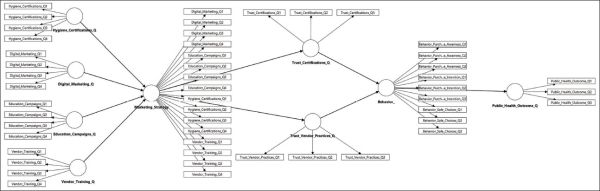

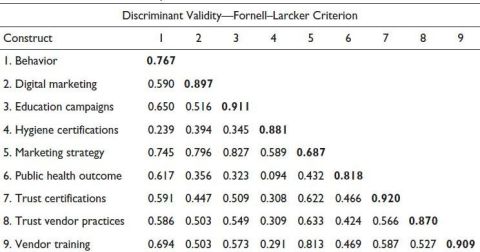

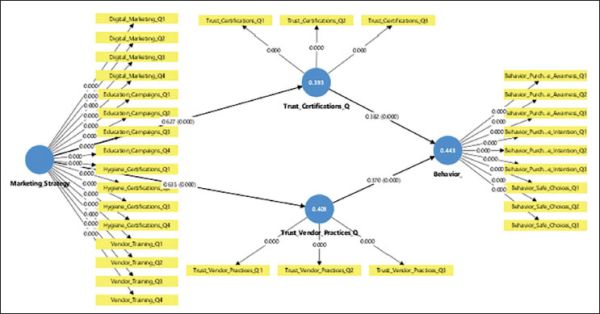

Figure 1. Structural Model Assessment.

Table 1. Measurement Model Assessment (Outer Loadings).

As shown in Table 1, most indicators exhibited satisfactory loadings (.png) 0.70), suggesting good indicator reliability. Exceptions include some indicators of Behavior_Purchase_Awareness (Q2 = 0.667; Q3 = 0.689) and Hygiene_Certifications (Q2 = 0.857 but cross-loading on Marketing_Strategy = 0.456), which, while slightly below the threshold in cross-loadings, were retained based on theoretical justification and internal consistency metrics.

0.70), suggesting good indicator reliability. Exceptions include some indicators of Behavior_Purchase_Awareness (Q2 = 0.667; Q3 = 0.689) and Hygiene_Certifications (Q2 = 0.857 but cross-loading on Marketing_Strategy = 0.456), which, while slightly below the threshold in cross-loadings, were retained based on theoretical justification and internal consistency metrics.

Cross-loadings were also evaluated to ensure discriminant validity, with all primary loadings significantly higher on their intended constructs than on others, supporting the model’s discriminant structure (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler et al., 2015) (see Table 1).

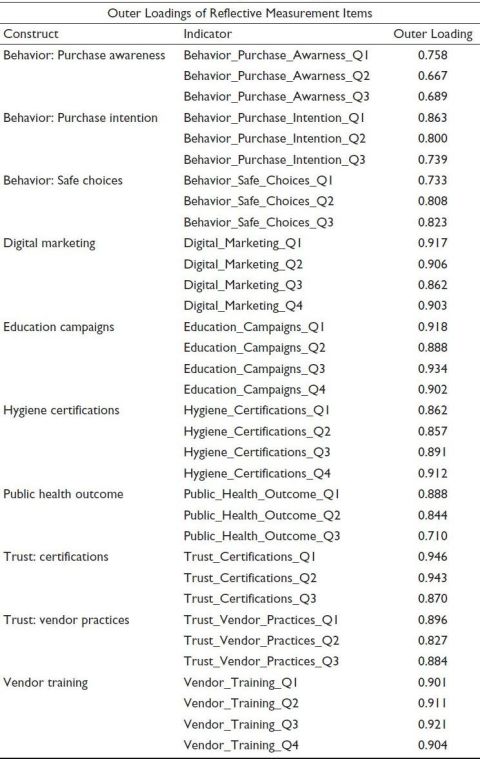

The reflective measurement model demonstrates strong psychometric properties as follows:

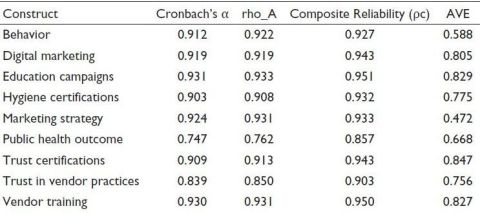

To evaluate the measurement model’s reliability and convergent validity, several metrics were assessed: Cronbach’s alpha, CR, rho_A, and AVE. According to Hair et al. (2021), values of

.png) 0.50 signifies adequate convergent validity, meaning the construct explains more than half of the variance in its indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).

0.50 signifies adequate convergent validity, meaning the construct explains more than half of the variance in its indicators (Fornell & Larcker, 1981).Key Findings:

The constructs in the model demonstrate strong internal consistency reliability and convergent validity, with the exception of marketing strategy, which showed marginal AVE. However, its high composite reliability and theoretical importance support its retention for structural modeling. The high CR values also suggest that the constructs are robust and reliable representations of their respective dimensions, which is critical for further structural model assessment and hypothesis testing. (See Table 2 and Figure 2.)

Table 2. Construct Reliability and Validity Analysis.

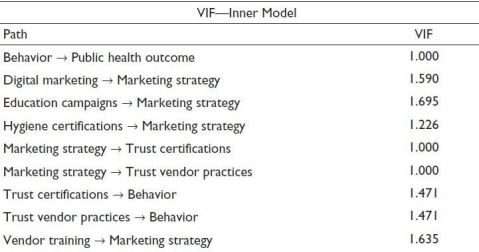

Discriminant validity refers to the extent to which a latent construct is truly distinct from other constructs, both conceptually and empirically. The Fornell–Larcker criterion (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) is one of the most established methods to assess this in PLS-SEM. It compares the square root of the AVE (diagonal elements) with the inter-construct correlations (off-diagonal elements). Discriminant validity is established when a construct’s square root of AVE exceeds its correlations with all other constructs.

Key Findings:

The results meet the Fornell–Larcker criterion across all constructs, confirming that each construct is empirically distinct from the others. This affirms the discriminant validity of the measurement model, a key prerequisite for valid interpretation of path relationships in the structural model (Hair et al., 2021) (see Table 3).

Figure 2. Measurement Model Assessment.

Table 3. Discriminant Validity Assessment: Fornell–Larcker Criterion.

Notes: Diagonal elements (in bold) are the square roots of AVE; off-diagonal elements are inter-construct correlations.

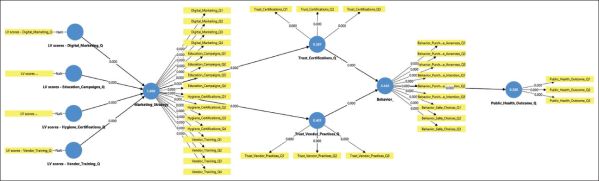

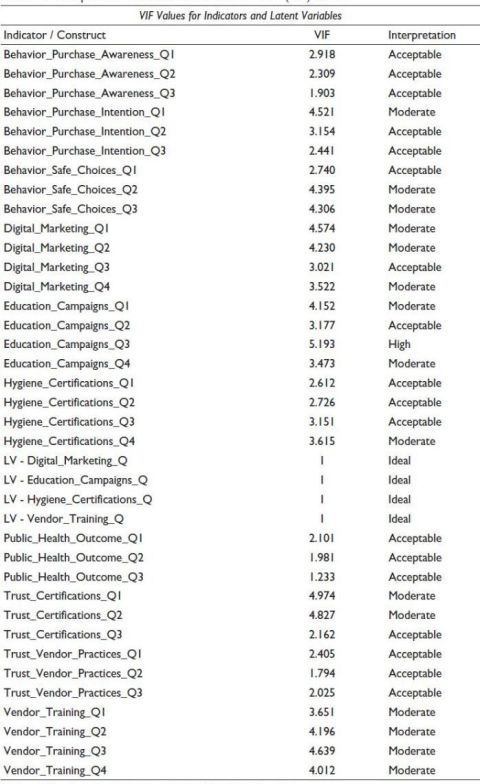

Collinearity Assessment (VIF)

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were used to detect multicollinearity. For outer model items, most VIFs were below the threshold of 5, indicating no severe collinearity issues (Hair et al., 2022).

All inner VIF values are below the conservative threshold of 3.3, confirming the absence of multicollinearity in the structural model (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2006) (see Table 4).

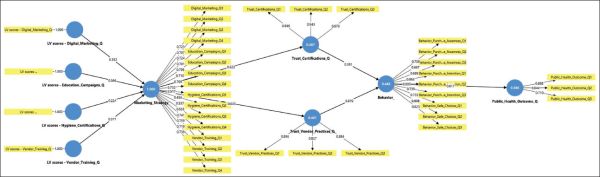

Structural Model Assessment

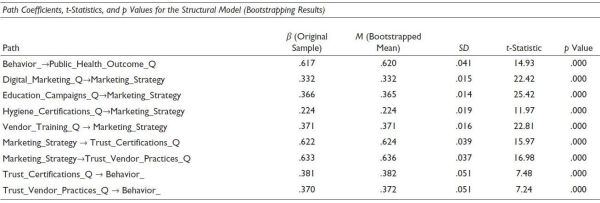

The structural model assessment evaluates the hypothesized relationships between latent variables (LV) using standardized path coefficients, their significance levels, and effect sizes. Based on the bootstrapping results (N = 5,000), the following observations can be made:

Table 4. VIF—Inner Model.

These findings align with prior research emphasizing the role of integrated marketing and trust-building in shaping consumer health behaviors and public health outcomes (Henseler et al., 2016; Hair et al., 2021) (see Figure 3 and Table 5).

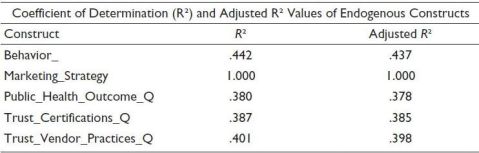

The coefficient of determination (R2) assesses the model’s explanatory power by indicating the proportion of variance in the endogenous (dependent) variables that can be explained by the exogenous (independent) constructs. According to Hair et al. (2021), R2 values of 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25 may be considered substantial, moderate, and weak, respectively, in social science research using PLS-SEM.

The results of the R2 and adjusted R2 values for the endogenous constructs are summarized below:

Figure 3. Structural Model Assessment.

Table 5. Path Coefficients, t-Statistics, and p Values for the Structural Model.

Notes: All path coefficients are significant at p < .001 based on 5,000 bootstrap samples.

β = Standardized Path Coefficient; M = Bootstrapped Mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

Table 6. Interpretation of coefficient of determination (R2) in the structural model.

Notes: R2 = Coefficient of determination. Adjusted R2 corrects for the number of predictors relative to the sample size. Marketing strategy is modeled as a higher-order construct with fixed R2.

These R2 values indicate that the model has a moderately strong capacity to explain consumer behavior and public health outcomes in the context of food safety interventions, aligning with recommended thresholds for applied behavioral and public health studies (Hair et al., 2021; Sarstedt et al., 2019).

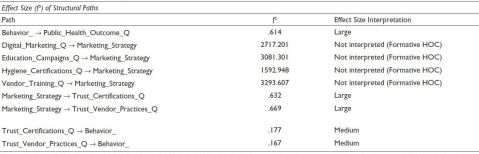

The effect size (f2) evaluates the individual impact of each exogenous (predictor) construct on its corresponding endogenous (outcome) variable in the structural model. It assesses how much an endogenous construct’s R2 value changes when a specific exogenous construct is removed from the model (Hair et al., 2021).

According to Cohen (1988), f2 values can be interpreted as follows:

However, extremely large values (e.g., in the thousands), such as those seen for digital marketing, education campaigns, vendor training, and hygiene certifications indicate that the endogenous variable (marketing strategy) is likely modeled as a second-order construct formed by its components. In such cases, these high f2 values are artifacts of model specification, not interpretable using Cohen’s benchmarks (Sarstedt et al., 2019).

Below is the scholarly interpretation of each path’s f2 effect size:

.png) Public_Health_Outcome_Q (f2 = 0.614): Large effect, indicating that behavior intentions strongly influence perceived public health outcomes.

Public_Health_Outcome_Q (f2 = 0.614): Large effect, indicating that behavior intentions strongly influence perceived public health outcomes..png) Trust_Certifications_Q (f2 = 0.632) and Trust_Vendor_Practices_Q (f2 = 0.669): Both paths show large effect sizes, emphasizing the critical role of marketing strategies in building trust in safety certifications and vendor practices.

Trust_Certifications_Q (f2 = 0.632) and Trust_Vendor_Practices_Q (f2 = 0.669): Both paths show large effect sizes, emphasizing the critical role of marketing strategies in building trust in safety certifications and vendor practices..png) Behavior_ (f2 = 0.177) and Trust_Vendor_Practices_Q

Behavior_ (f2 = 0.177) and Trust_Vendor_Practices_Q .png) Behavior_ (f2 = 0.167): Medium effects, suggesting that both trust dimensions moderately contribute to influencing behavioral outcomes.

Behavior_ (f2 = 0.167): Medium effects, suggesting that both trust dimensions moderately contribute to influencing behavioral outcomes.The VIF is a diagnostic measure used to assess multicollinearity among indicators or constructs in SEM. Multicollinearity occurs when two or more indicators or constructs are highly correlated, which can distort estimates of path coefficients and reduce the stability of the model (Hair et al., 2021).

Guidelines for Interpreting VIF

Education_Campaigns_Q3 = 5.193, Trust_Certifications_Q1 = 4.974, Trust_Certifications_Q2 = 4.827. These values are on the higher side of acceptability but not necessarily problematic unless accompanied by other signs of model instability or suppression effects.

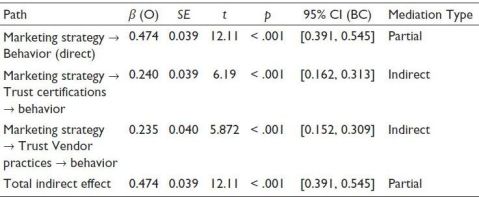

Mediation Analysis

A mediation model was tested to examine whether trust in certifications and trust in vendor practices mediate the relationship between marketing strategy and consumer behavior in the context of street food safety.

Table 7. Interpretation of Effect Size (f2) in the Structural Model.

Notes: f2 values > 0.35 indicate large effect sizes. Exceptionally large f2 values for the indicators of marketing strategy are due to the formative model specification and are not directly interpretable using Cohen’s guidelines.

Table 8. Interpretation of Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) Values.

Notes. VIF values above 5 suggest potential multicollinearity.

All LV scores exhibit ideal VIF = 1.

Direct Effects

The direct path from Marketing Strategy .png) Behavior was significant (β = 0.474, t = 12.11, p < .001), indicating a strong direct influence of marketing strategies on consumer behavior. Additionally, marketing strategy significantly predicted trust in certifications (β = 0.627, t = 16.569, p < .001) and trust in vendor practices (β = 0.635, t = 17.387, p < .001). Both mediators also had significant effects on Behavior: Trust in Certifications

Behavior was significant (β = 0.474, t = 12.11, p < .001), indicating a strong direct influence of marketing strategies on consumer behavior. Additionally, marketing strategy significantly predicted trust in certifications (β = 0.627, t = 16.569, p < .001) and trust in vendor practices (β = 0.635, t = 17.387, p < .001). Both mediators also had significant effects on Behavior: Trust in Certifications .png) Behavior (β = 0.382, t = 7.46, p < .001) and Trust in Vendor Practices

Behavior (β = 0.382, t = 7.46, p < .001) and Trust in Vendor Practices .png) Behavior (β = 0.370, t = 7.186, p < .001).

Behavior (β = 0.370, t = 7.186, p < .001).

Indirect Effects

The total indirect effect of marketing strategy on behavior was also significant (β = 0.474, t = 12.11, p < .001), with a bias-corrected 95% confidence interval [0.391, 0.545], indicating mediation.

Interpretation

Both trust in certifications and trust in vendor practices partially mediate the relationship between marketing strategy and behavior. The presence of a significant direct effect alongside significant indirect effects supports partial mediation, indicating that marketing strategies influence behavior both directly and indirectly through increased trust in food safety mechanisms.

Practical Implications

The results highlight the pivotal role of trust-building mechanisms in converting strategic marketing efforts into behavioral change among consumers. Public health authorities and food vendors should integrate hygiene certifications and transparent vendor practices into their marketing strategies to strengthen consumer trust and encourage safe food consumption behaviors in urban street food environments.

Table 9. Mediation Model.

Figure 4. Mediation Analysis.

Discussion

This study investigated the role of marketing strategies in influencing public trust and consumer behavior toward street food safety, using a structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) approach. The findings highlight the multifaceted impact of marketing interventions—specifically vendor training, digital marketing, hygiene certifications, and educational campaigns—on trust constructs and downstream behavior.

Marketing Strategies and Trust Formation

The results reveal that marketing strategies significantly affect trust in both food certifications (β = 0.622, p < .001) and vendor practices (β = 0.633, p < .001). The corresponding effect sizes (f2 = 0.632 and 0.669) suggest a substantial influence, affirming prior literature that associates marketing cues and institutional endorsements with trust in food safety contexts (Kähkönen & Tuorila, 2015; McEachern & Warnaby, 2008). Trust in certifications represents institutional trust, while trust in vendor practices reflects interpersonal trust, corroborating the dual trust framework suggested by Frewer et al. (1996).

Trust as a Mediator of Behavioral Change

Both trust in certifications (β = 0.381) and vendor practices (β = 0.370) significantly predict safe behavioral intentions (p < .001), supporting models such as the TPB (Ajzen, 1991) and extensions of the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974 ).The findings position trust as a vital mediating variable, transforming marketing signals into tangible behavioral outcomes such as increased awareness, intention to purchase safely, and cautious vendor selection.

Implications for Urban Food Safety Governance

The model’s explanatory power is considerable, with R2 values of 0.442 for behavior and around 0.40 for trust constructs. Among all antecedents, vendor training demonstrated the highest impact on the marketing strategy latent variable (f2 = 3293.61), followed by educational campaigns (f2 = 3081.30), digital marketing (f2 = 2717.20), and hygiene certifications (f2 = 1592.95). These insights underscore the practical importance of capacity building among vendors, digital outreach, and formal hygiene endorsements as integrated tools for health communication.

In urban street food ecosystems, where regulatory oversight is fragmented, this study demonstrates how social marketing interventions can bridge institutional gaps. Public health authorities can enhance food safety by combining formal certification mechanisms with informal trust-building techniques such as vendor visibility, hygiene signage, and behavior reinforcement.

Conclusion

Summary of Findings

This study empirically validates a conceptual model in which marketing strategies exert indirect effects on food safety behavior via trust. It confirms that trust in both vendors and certifications is a significant predictor of public behavior, and marketing strategies are effective levers for enhancing that trust.

Theoretical Contributions

Managerial and Policy Implications

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Further studies may also explore the use of experimental and longitudinal designs to validate intervention effects over time and across diverse urban geographies.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Nilanjan Ray  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6109-6080

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6109-6080

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ali, J., & Nath, T. (2013). Factors affecting consumers’ perception on food safety. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 19(2), 100–112.

Banik, S., et al., (2021). Evaluating street food vendor hygiene and consumer perception in urban India. Food Control, 124, 107897.

Barro, N., et al., (2006). Street-vended foods improvement: Contamination mechanisms and application of food safety criteria. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 32(4), 275–293.

Becker, J. M., Klein, K., & Wetzels, M. (2012). Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Planning, 45(5–6), 359–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2012.10.001

Chen, M. F. (2013). Influencing factors of consumer food safety behavioral intention. British Food Journal, 115(3), 397–410.

Choudhury, M., et al., (2011). Hygiene practices of street food vendors in urban India. Journal of Public Health, 33(3), 282–287.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2006). Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. British Journal of Management, 17(4), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2006.

00500.x

Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

Earle, T. C., & Siegrist, M. (2008). Trust, confidence and cooperation model: A framework for understanding the relation between trust and risk perception. International Journal of Global Environmental Issues, 8(1–2), 17–29.

FAO. (2016). Street food vending in the developing world. Food and Agriculture Organization.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Frewer, L. J., Howard, C., Hedderley, D., & Shepherd, R. (1996). What determines trust in information about food-related risks? Underlying psychological constructs. Risk Analysis, 16(4), 473–486.

FSSAI. (2021). Clean street food hub guidelines. Food Safety and Standards Authority of India.

Grunert, K. G. (2005). Food quality and safety: Consumer perception and demand. European Review of Agricultural Economics, 32(3), 369–391.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Impact of hotel-restaurant image and trust on intentions related to loyalty. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 63, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.03.006

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based SEM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431.

Kähkönen, P., & Tuorila, H. (2015). Consumer preferences for food packaging and labels in relation to trust and safety. Appetite, 96, 142–150.

Kapoor, K., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2020). Metaphors of digital transformation in food marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 355–377.

Kumar, D., & Kapoor, S. (2017). Perception of hygiene and safety in street food among Indian urban consumers. Food Control, 81, 101–108.

Liu, R., et al., (2014). Factors influencing consumer purchase intentions for green food in China. Appetite, 79, 155–163.

Lobb, A. E., Mazzocchi, M., & Traill, W. B. (2007). Modelling risk perception and trust in food safety information within the theory of planned behaviour. Food Quality and Preference, 18(2), 384–395.

Majumder, T., & Mukherjee, A. (2023, July 14). Medical and e-waste management: Emerging challenges in public health. BIMS Journal of Management, 8(1), 9–17.

Majumder, T., Ray, N., Mutsuddi, I., & Roy, M. (2025). Harmonizing sustainable management of medical and e-waste with AI in the face of climate change. In R. K. D. Dubey, I. Mutsuddi, S. Das, S. Das, & N. Ray (Eds.), Contemporary business practices and sustainable strategic growth (Chapter 5). Bentham Books. https://doi.org/10.2174/9789815322071125010005

McEachern, M. G., & Warnaby, G. (2008). Exploring the relationship between consumer knowledge and attitudes towards organic food. British Food Journal, 110(11), 1137–1150.

Olson, J. C., & Jacoby, J. (1972). Cue utilization in the quality perception process. In M. Venkatesan (Ed.) Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research (pp. 167–179). Association for Consumer Research.

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2017). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., & Vomberg, A. (Eds.), Handbook of market research (pp. 1–40). Springer.

Soon, J. M., Baines, R., & Seaman, P. (2012). Meta-analysis of food safety training on improving knowledge among food handlers. Journal of Food Protection, 75(5), 793–804.

Sparks, P., et al., (2014). Food choice and consumption: Strategies and interventions to promote healthy eating. Appetite, 82, 36–47.

Wang, O., et al., (2019). Effects of certification credibility and label format on green food purchase intentions. British Food Journal, 121(8), 1868–1882.

WHO. (2020). Food safety and street foods: A public health challenge. World Health Organization.

Yeung, R. M. W., & Morris, J. (2001). Food safety risk: Consumer perception and purchase behavior. British Food Journal, 103(3), 170–187.