1School of Management Studies, GIET University, Gunupur, Rayagada, Odisha, India

2Department of Commerce, North East Hill University, Shillong, Meghalaya, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

India’s indigenous economic practices, policies and novel, frugal innovations are fine testaments to its Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). Contributing around 30% of the national GDP, they act as a cornerstone of the Indian economy. However, driven mainly by conventional methodologies, integrating sustainability into operations has been a far cry. In the digital era, aligning sustainability with digital transformation—termed ‘digital sustainability’—requires new organisational capabilities. This study explores how Indian SMEs can develop digital sustainability capabilities (DSCs), drawing on the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory. With a blend of methodological approaches, including a survey of more than 300 SMEs and interviews with 25 SME leaders across sectors, this research identifies the enablers, barriers and impact of digital sustainability initiatives on firm performance. Findings show that strategic alignment, digital leadership and ecosystem engagement are key to developing DSCs.

Digital sustainability, SMEs, strategic alignment, ecosystem engagement, capability development

Introduction

The economic landscape of post-colonial states (some of them are now emerging economies), like India, is highly fragmented. The disproportionate concentration of wealth creates a broader range of the economic spectrum. The core is inflated with capital. Hence, the probability of big enterprises emerging from this class is higher. However, the strengths of this segment are very few. Hence, the number of bigger enterprises is following suit. The middle segment, due to structural inequality, suffers from inequitable access to capital. This becomes a significant barrier for them to create large enterprises. Hence, they resort to Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs). The width of this segment is comparatively large. Thus, SMEs are dotted across the spectrum. They play a central role in the economic landscape of emerging economies, like in India, contributing approximately 30% to the nation’s GDP and employing over 100 million people (MSME Ministry, 2023). However, Indian SMEs face a dual imperative: achieving digital transformation while aligning with global sustainability standards (Bag et al., 2023; Chatterjee et al., 2022). Co-opting these priorities, known as digital sustainability, is increasingly recognised as a strategic frontier for firms aiming to remain competitive, innovative and socially responsible (Ciasullo et al., 2023; Teece, 2021).

The concept of digital sustainability has been defined as ‘the organisational activities aimed at the advancement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through creative implementation of technologies covering the end-to-end value chain of electronic data (George et al., 2020, p. 1000)’. It refers to the use of digital technologies to support environmental, social and governance (ESG) objectives (Elia et al., 2022; Kraus et al., 2022). It requires a rethinking of business models, realignment of objectives, reconfiguration of capabilities and re-evaluation of stakeholder relationships to ensure that digital initiatives contribute meaningfully to long-term, SDGs (Troise et al., 2023). While large corporations are progressively embedding sustainability into digital operations, the picture is more complex for SMEs. Their size, informality and resource limitations hinder their ability to make such systemic transitions (Ardito et al., 2023; Scuotto et al., 2022).

Recent literature has demonstrated that SMEs must develop new organisational capabilities to engage in digital sustainability, including adaptive leadership, strategic alignment and multi-stakeholder collaboration (Ghobakhloo & Fathi, 2021; Shah et al., 2023). However, existing studies have primarily focused on either digital transformation or sustainability in isolation (Bressan et al., 2022; Ferreira et al., 2023). The integrated capability development process—especially in resource-constrained environments like India—is understudied. Moreover, much of the current literature is situated in high-income contexts, leaving a gap in understanding the unique challenges and enablers for SMEs in emerging markets (Issa et al., 2023; Zangiacomi et al., 2022).

In India, several government initiatives, such as the Digital MSME Scheme, Zero Defect Zero Effect (ZED) certification and sustainability-linked credit guidelines, are encouraging SMEs to digitise while becoming environmentally responsible (Deloitte, 2023). However, uptake remains fragmented and heavily skewed towards tech-savvy urban firms (Narayan et al., 2023). SMEs in semi-urban and rural areas often lack the absorptive capacity to align digital adoption with sustainability frameworks (Mitra & Reddy, 2023). Furthermore, the institutional voids and weak digital ecosystems exacerbate this gap (Bag & Pretorius, 2022; Bharadwaj et al., 2023).

Emerging studies suggest that the capability of integrating sustainability into digitalisation is not merely technological but also organisational and relational (Feroz et al., 2022; Rashid et al., 2022). This involves systematic overhauls, realignments and reconfiguration of existing norms and practices, as well as scenario mapping that factors in environmental trends and patterns, investing in human capital and engaging with broader ecosystems of suppliers, regulators and consumers (Popovi.png) et al., 2023; Raimo et al., 2022). SMEs that develop such digital sustainability capabilities (DSCs) are better positioned to generate both economic and socio-environmental returns (Ali et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023).

et al., 2023; Raimo et al., 2022). SMEs that develop such digital sustainability capabilities (DSCs) are better positioned to generate both economic and socio-environmental returns (Ali et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023).

Theoretically, the integration of resource-based view (RBV) and dynamic capability theory (DCT) offers a compelling lens to understand how SMEs build and leverage capabilities in turbulent contexts (Papadopoulos et al., 2022; Teece et al., 2021). While RBV highlights the importance of rare and inimitable resources, DCT emphasises the firm’s ability to sense, seize and transform resources in response to environmental change (Ardito et al., 2023; Dwivedi et al., 2023). This theoretical synthesis enables us to conceptualise DSCs not as static assets but as evolving capabilities shaped by leadership, strategy and ecosystem collaboration (Fernandes et al., 2023; Kraus et al., 2022).

Despite these theoretical insights, empirical evidence on the capability development process for digital sustainability in Indian SMEs is limited. What specific organisational resources and external linkages enable SMEs to build such capabilities? How do these capabilities influence innovation and firm performance? Moreover, what role do mediating factors, such as ecosystem engagement, play in this process? These are crucial questions for both scholars and policymakers interested in inclusive, tech-enabled and sustainable growth pathways in emerging markets.

Accordingly, this study seeks to fill the empirical and theoretical gaps by examining how Indian SMEs develop DSCs and how these capabilities influence firm performance. It integrates insights from empirical research (2021–2024), applies a dynamic capabilities perspective and deploys a mixed-methods approach to offer comprehensive evidence on this timely and important topic.

Review of Literature

Digital sustainability represents the integration of digital technologies (artificial intelligence [AI], the Internet of Things [IoT], blockchain and data analytics) into sustainability agendas to achieve ESG outcomes and progress towards SDGs (Ciasullo et al., 2023; Elia et al., 2022; Kraus et al., 2022). For SMEs, digital sustainability is both a performance lever and a resilience mechanism (Ali et al., 2023; Bag et al., 2023; Feroz et al., 2022). Systematic reviews indicate that while larger firms lead in such integration, SMEs lag due to limited capacity (Melo et al., 2023; Toth-Peter et al., 2023; Yadav & Gahlot, 2022).

DSCs are understood as dynamic, evolving and firm-specific (Ardito et al., 2023; Ghobakhloo & Fathi, 2021; Teece, 2021, 2022). Studies confirm that these capabilities stem from sensing–seizing–transforming mechanisms (Bai et al., 2023; El Idrissi et al., 2023; Souza et al., 2024). Recent SME-focused research also highlights digital literacy and human capital as key dynamic capabilities (GonzálezVarona et al., 2024; Rashid et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2022).

A strong digital strategy aligned with sustainability goals is crucial for the performance and environmental impact of SMEs (Adomako et al., 2021; Ivanova, 2020; Nayal et al., 2022). Leadership plays a central enabling role: digital-savvy leaders with strategic vision drive DSC maturity (Bag & Pretorius, 2022; Fernandes et al., 2023; Shah et al., 2023). Equally, ecosystem engagement—including collaboration with suppliers, customers, regulators and industry networks—amplifies capabilities and accelerates sustainable digital innovation (Issa et al., 2023; Raimo et al., 2022; Troise et al., 2023).

SMEs in regions like India face multiple constraints, including limited financial resources, poor infrastructure, technical skills gaps, regulatory ambiguity and weak digital ecosystems (Ghobakhloo & Iranmanesh, 2021; Mitra & Reddy, 2023; Mohapatra & Thakurta, 2019; Narayan et al., 2023). These inhibitors exacerbate the digital–sustainability divide, particularly in semi-urban and rural areas (Bag & Pretorius, 2022; Bharadwaj et al., 2023).

Digital tools enable SMEs to implement circular economy principles, such as closing resource loops, reducing waste and enabling product-as-service models (Das, 2025; Raut et al., 2022; Zahoor & Lew, 2023). Studies in Indian textile SMEs emphasise digital-enabled circularity as a pathway to both cost efficiency and environmental sustainability (Das, 2025).

There is strong evidence that DSCs enhance firm performance– operational efficiency, innovation, environmental compliance and market reach (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Nwankpa & Roumani, 2016; Ul Haq et al., 2022). However, measurement frameworks remain fragmented, with calls for integrative metrics that combine financial, environmental and social dimensions growing (Costa Melo et al., 2023; Philbin et al., 2022; Silva et al., 2022).

Research Gaps

Driven by global imperatives such as the United Nations’ SDGs-2030, the growing role of data-driven technologies and mounting environmental pressures (Elia et al., 2022; Kraus et al., 2022), the integration of digital transformation and sustainability has garnered considerable scholarly attention in recent years. Although studies acknowledge the importance of aligning digitalisation with sustainable outcomes, significant gaps remain in the SMEs in developing economies such as India.

Current research in the domains of digital transformation and corporate sustainability is often siloed. Many studies focus either on the adoption of digital technologies (e.g., AI, IoT and blockchain) to improve firm competitiveness (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Ghobakhloo & Iranmanesh, 2021) or on sustainability practices for resource optimisation and regulatory compliance (Ciasullo et al., 2023; Feroz et al., 2022). There is limited scholarly work that systematically integrates these two streams to examine how SMEs can build DSCs that deliver both technological and ESG values.

The vast majority of existing studies on DSCs are grounded in large firms or multinational corporations, primarily in developed countries (Ardito et al., 2023; Teece, 2021). Despite comprising over 90% of firms globally and acting as a critical platform for employment and local development, SMEs remain significantly underrepresented in this discourse. In particular, the unique capability-building challenges faced by SMEs, such as resource constraints, limited absorptive capacity and a lack of formalised strategies, are not sufficiently addressed in the existing literature (Bag et al., 2023; Shah et al., 2023).

While studies have begun exploring digital sustainability in high-income regions, there is a lack of empirical research from emerging markets, where institutional voids, infrastructural limitations and regulatory ambiguities shape firm behaviour in distinct ways (Mitra & Reddy, 2023; Bharadwaj et al., 2023). In the Indian context, although government initiatives such as Digital MSME and the ZED certification scheme encourage sustainable digitisation, there is limited academic enquiry into how SMEs operationalise these policies and what internal and external capabilities enable such transitions.

Existing research tends to treat digital sustainability either as a technological upgrade or as a compliance mechanism without grounding it in a strong theoretical framework. Few studies apply integrative theories such as the RBV and DCT to explain how SMEs sense, seize and reconfigure capabilities for sustainable digitalisation (Papadopoulos et al., 2022; Rashid et al., 2022). Moreover, the concept of DSCs remains conceptually unorganised and underdeveloped, with no universally accepted operationalisation, particularly in resource-constrained settings such as India.

Research has largely overlooked the relational dimension of digital sustainability, including how SMEs engage with external stakeholders such as supply chains, digital platforms, customers, regulators and NGOs to build capabilities (Issa et al., 2023; Troise et al., 2023). In addition, few studies disaggregate findings by sector (e.g., manufacturing vs services) or by region (e.g., urban vs rural SMEs), ignoring the heterogeneity within the SME ecosystem and its implications for capability development pathways.

While some studies associate digital or sustainability practices with improved firm performance, there is a limited empirical analysis of how DSCs directly influence operational, financial and environmental outcomes in SMEs (Costa Melo et al., 2023; Silva et al., 2022).

The broader impacts of digital sustainability investments have subsided mainly due to their qualitative nature, higher degree of subjectivity and lack of multidimensional aspects.

Research Objectives and Questions

Research Objectives

The primary objective of this study is to investigate how DSCs are perceived, construed, developed, nurtured, deployed and translated into performance outcomes within the Indian parlance of SMEs. The study seeks to bridge the theoretical and empirical gap by adopting an integrated approach that combines the RBV and DCT to explore the intersection of digital transformation and sustainability in SMEs operating in resource-constrained and institutionally complex environments.

Research Questions

Building on the above objectives and gaps identified in the extensive literature, the following research questions (RQs) guide the study:

RQ1: What is the compositional mix of DSCs in Indian SMEs, and how can they be conceptualised and measured?

This question addresses the need to define DSCs in a context-specific manner, capturing both digital and sustainability dimensions tailored to Indian SMEs.

RQ2: What are the key internal organisational enablers (e.g., strategic alignment and digital leadership) that influence the development of DSCs?

This question focuses on the role of internal resources, competencies and strategic intent in capability-building.

RQ3: How does ecosystem engagement mediate or moderate the relationship between internal enablers and the development of DSCs?

This research question examines how external stakeholder collaboration facilitates or hinders the evolution of capability.

RQ4: What is the relationship between DSCs and firm performance outcomes (e.g., innovation, environmental compliance and customer satisfaction)?

This question examines whether and how DSCs translate into tangible benefits for SMEs.

RQ5: How do sectoral and regional factors (e.g., manufacturing vs. services, urban vs. rural settings) shape the capability development pathways for digital sustainability in SMEs?

This question investigates contextual variations that influence the design and implementation of DSC strategies.

Hypothesis Development

This study develops a set of hypotheses that link organisational enablers, ecosystem engagement and performance outcomes in the context of DSCs within Indian SMEs.

Strategic Alignment and DSC Development

Strategic alignment refers to the degree of integration of an SME’s digital strategy with its sustainability objectives. A firm with high strategic alignment is more likely to allocate resources effectively, avoid duplication of efforts and sustain digital investments over time (Ciasullo et al., 2023; Nayal et al., 2022). Studies have shown that strategic clarity enhances a firm’s ability to prioritise digital tools that directly support environmental and social goals (Papadopoulos et al., 2022). Therefore, SMEs having strong strategic alignment are most likely to develop durable DSCs.

H1: Strategic convergence between digitalisation and sustainability is positively associated with the development of DSCs in SMEs.

Leadership and Capability Creation

Leadership is a crucial pivot to any organisational transformation. In the context of digital sustainability, leaders who are digitally literate and environmentally conscious can foster a culture that promotes innovation, risk-taking and long-term thinking (Bag & Pretorius, 2022; Shah et al., 2023). Leadership commitment also enhances absorptive capacity and knowledge integration, which are essential for the sensing, seizing and transforming phases of capability development (Teece et al., 2022).

H2: Digital sustainability leadership has a positive influence on the development of DSCs in SMEs.

Ecosystem Engagement as a Mediator

Ecosystem engagement refers to a firm’s interaction with external stakeholders, including suppliers, customers, regulators, NGOs and technology providers. Prior studies have emphasised that stakeholder collaboration enhances learning opportunities, increases access to knowledge related to sustainability and supports digital adoption (Issa et al., 2023; Troise et al., 2023). Ecosystem engagement can thus serve as a mediating mechanism that links internal enablers (e.g., strategy and leadership) with capability development.

H3a: Ecosystem engagement positively influences the development of DSCs in SMEs.

H3b: Ecosystem engagement mediates the relationship between strategic alignment and the development of DSCs.

H3c: Ecosystem engagement mediates the relationship between digital leadership and the development of DSCs.

Sectoral and Regional Context as Moderators

Emerging evidence suggests that SMEs do not operate in a uniform environment. Sectoral characteristics (e.g., product complexity, regulation and supply chain integration) and regional factors (e.g., urban versus rural infrastructure) influence the availability and effectiveness of capability-building mechanisms (Das, 2025; Mitra & Reddy, 2023). For instance, manufacturing SMEs may require more sophisticated digital infrastructure for sustainability integration than service-oriented firms.

H4a: The relationship between internal enablers (strategic alignment and leadership) and DSCs is moderated by the SME sector (manufacturing vs services).

H4b: The relationship between ecosystem engagement and DSCs is moderated by regional digital infrastructure (urban vs rural).

Impact of DSCs on Firm Performance

DSCs are expected to enhance multiple dimensions of firm performance. This includes operational efficiency, environmental compliance, innovation and market competitiveness (Costa Melo et al., 2023; Dwivedi et al., 2023). These capabilities enable SMEs to reconfigure their processes, becoming more resilient and future-ready.

H5a: DSCs positively influence environmental performance in SMEs.

H5b: DSC holds a positive association with operational performance

H5c: DSC positively influences innovation performances.

H5d: DSC positively influences customer satisfaction and market reputation.

Conceptual Framework

Theoretical Background

The study is grounded in two complementary theories at the conceptual level.

The resource-based view (RBV) emphasises that sustained competitive advantage stems from a firm’s ability to possess and employ valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN) resources (Barney, 1991). In this view, digital technologies and sustainability competencies are increasingly recognised as strategic resources.

DCT (Teece, 2007) expands RBV and acts as a Scenario mapping module. It explains the adaptability of firms to the rapidly changing environmental factors. It senses the dynamism of the ecosystem, identifies opportunities and threats, develops plans to capitalise on them, and transforms its resource base. This theory resonates with SMEs' operations, which predominantly take place in a VUCA environment. There, sustainability demands agility and continuous learning.

Together, these perspectives guide the design of a capability-centric framework for understanding how Indian SMEs develop, leverage, and benefit from DSCs.

Constructs and Relations

Internal Enablers

Factors such as strategic alignment and digital leadership fall under this category. They serve as foundational forces within the firm that catalyse the development of DSCs. Strategic alignment refers to the deliberate integration of digital transformation goals with sustainability imperatives across organisational planning, investment and operational domains. When SMEs find strategic fits, they align their environmental objectives with digital strategies. They invest in technology solutions that generate both economic and ecological values. This alignment lays the foundation for coherent decision-making, enabling firms to avoid fragmented or redundant efforts. Digital leadership, on the other hand, represents the influence of forward-thinking leaders who champion sustainability and innovation. In SMEs, decision-making is often centralised. The role of one person or a small group of people is crucial in crafting and setting a vision, allocating resources and nurturing a cultural ecosystem that fosters continuous learning and experimentation. Leaders who have an orientation about emerging technologies and are committed to environmental goals can serve as catalysts for embedding sustainability into digital initiatives. In toto, these internal enablers drive not only technological adoption but also organisational readiness for sustainability transitions.

Ecosystem Engagement (Mediator)

It acts as a critical mediating mechanism in the development of DSCs by enabling SMEs to extend their resource and knowledge base beyond internal confines. SMEs typically operate with constrained capacities. Therefore, their ability to interact with external stakeholders, such as technology vendors, supply chain partners, academic institutions and government bodies, becomes essential for enhancing their capabilities. This can be made possible through agile networking. Active participation in innovation clusters, industry associations and public–private partnerships can help SMEs gain access to technical expertise, policy incentives and legitimacy. All of these facilitate the integration of digital technologies with sustainability goals. This circular ecosystem facilitates co-creation and learning. It enables firms to adopt best practices and proctored solutions to local contexts. Ecosystem engagement serves as both a channel for resource acquisition and a platform for institutional support. It thus helps in bridging the gap between strategic intent and operational capability, reinforcing the pathways through which internal enablers influence DSC development.

Contextual Moderators

Variations, such as sectoral and regional conditions, are elementary in shaping and moulding the intensity and effectiveness of capability development processes in SMEs. Sectoral variation—especially between manufacturing, services and agri-tech—affects the nature of digital sustainability needs, regulatory pressures and technology applicability. For example, manufacturing firms may focus on energy efficiency and emissions monitoring, while service sector SMEs may prioritise digital workflows and green customer engagement. Likewise, regional context—including differences between urban, semi-urban and rural areas—impacts access to digital infrastructure, policy support, talent and innovation ecosystems. SMEs in urban areas are more likely to be exposed to sustainability-driven market demands and digital service providers. Residents in marginalised geographies, such as rural areas and hinterlands, struggle with connectivity and access to institutional resources. These contextual structural factors moderate the relationships between enablers, capabilities and outcomes by either facilitating or constraining the adoption and performance impact of DSCs.

Digital Sustainability Capabilities

These constitute the core construct of this framework, representing the firm’s ability to integrate digital technologies into environmental and social sustainability practices. Unlike isolated technology use or compliance-focused sustainability efforts, DSCs are conceived as dynamic capabilities—bundles of routines and processes that enable ongoing adaptation, innovation and value creation. In SMEs, DSCs may manifest in various forms, such as utilising IoT for resource monitoring, deploying AI for predictive maintenance to reduce waste, automating regulatory reporting or enabling circular economy practices through digital platforms. These capabilities are shaped by internal leadership and strategy, reinforced through ecosystem interactions and continuously reconfigured in response to external changes. As such, DSCs not only reflect the current technological maturity of a firm but also its learning orientation and strategic agility in aligning digital innovation with sustainability imperatives.

Performance Outcomes

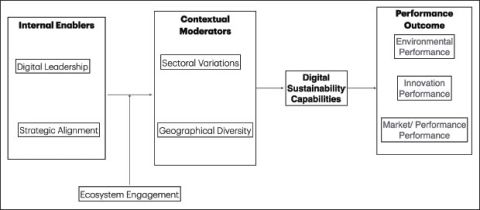

The ultimate expression of capability effectiveness in this framework is this set of outcomes. They are multidimensional and encompass both the tangible and intangible benefits derived from the development and application of DSCs. Environmental performance refers to reductions in emissions, waste and resource consumption, as well as enhanced compliance with environmental regulations. Operational performance captures gains in process efficiency, cost savings and error reduction. Innovation performance reflects the firm’s ability to generate new green products, services or business models, while market/customer performance relates to enhanced brand reputation, customer loyalty and competitive positioning. It structures outcomes across these four domains. The framework thus transcends narrow financial metrics to provide a comprehensive view of SME performance in a sustainability-driven digital economy. The bridge between DSCs and performance outcomes underscores the strategic importance of digital sustainability in building resilience and long-term value in emerging market enterprises. The interrelationships between internal enablers, ecosystem engagement, contextual moderators, and firm performance outcomes are summarised in the conceptual framework (Figure 1).

Visual Representation of the Conceptual Framework

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework.

Novelty and Contribution of the Framework

The proposed conceptual framework offers a novel and context-specific contribution to the emerging discourse on digital sustainability by situating SMEs in India at the centre of enquiry—an area often overlooked in mainstream sustainability and digital transformation literature. Unlike prior models that primarily focus on large firms or treat digitalisation and sustainability as separate streams, this framework integrates both within a dynamic capabilities perspective tailored to resource-constrained environments. Its originality lies in conceptualising DSCs as a distinct and measurable construct shaped by the interplay of strategic alignment, digital leadership and ecosystem engagement—a triadic approach not yet fully explored in empirical studies. Furthermore, by linking DSCs to multiple dimensions of performance (environmental, operational, innovation and customer centric), the framework expands our understanding of how sustainability-oriented digital investments translate into tangible outcomes. It also introduces contextual moderators, such as sectoral and regional variations, highlighting that the digital sustainability journey is not uniform across SMEs. Thus, this framework not only fills a significant empirical gap in the Global South but also extends the theoretical boundaries of the RBV and DCT by embedding sustainability imperatives into digital capability development.

Empirical Setting and Methodology

Empirical Setting

Indian SMEs encounter externalities such as resource constraints, regulatory pressures, and digital disparities, particularly between urban and semi-urban regions. This makes the system of operations extremely complex. The convergence of digitalisation and sustainability has emerged as both a challenge and an opportunity for these firms. Due to environmentalism, the pressure to adopt environmentally responsible practices has intensified. Rising consumer awareness, ESG mandates, and supply chain expectations have made it even more pressing. Digital advancements ranging from cloud computing and IoT to AI and blockchain, on the other hand, offer transformative potential for monitoring, optimising, and innovating towards sustainability. The adoption and integration of these technologies, however, have been uneven. They have often been hindered by limitations such as gaps in strategic vision, digital skills and institutional support. This makes Indian SMEs a compelling empirical setting to examine how DSCs are formed, shaped, and applied in practice. The study focuses on four Indian states- Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Odisha, and Gujarat. Thus, it captures the heterogeneity of industrial infrastructure, policy environments, and ecosystem maturity. The empirical analysis, therefore, not only reflects the realities of capability-building in emerging markets but also provides rich ground for theoretical contributions to the understanding of digital sustainability transitions in resource constrained environments.

Research Design

This study employs a mixed-methods explanatory sequential research design to investigate the development of DSCs in Indian small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The research is grounded in the integration of the RBV and DCT, providing a robust theoretical foundation to explore both internal and external enablers of capability formation. The design began with a qualitative exploratory phase. During this, semi-structured interviews were conducted with SME leaders, digital consultants, and ecosystem stakeholders. Insights from this phase helped refine construct definitions, identify contextual nuances, and ensure cultural and operational relevance. They cumulatively laid foundation for the development of a structured survey instrument. The instrument is used in the quantitative phase to empirically validate the conceptual model. This sequential design allowed for theoretical grounding and contextual sensitivity. It was followed by generalisable empirical testing. The quantitative component was based on a cross-sectional survey distributed to SMEs across four Indian states. It enabled a diverse yet focused data collection effort. Structural equation modelling (SEM) has been used to evaluate the proposed relationships. Bootstrapping and multi-group analysis added robustness to the inferential framework.

Data Collection

Sampling Method

A purposive stratified sampling strategy was employed to ensure representation across key dimensions, such as sector, geography and firm size, which are relevant to the study. Given the diversity of the Indian SME landscape, the sample was drawn from four states: Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Odisha and Gujarat, representing varying levels of digital infrastructure, industrial development and sustainability policy exposure. Within these states, SMEs were further stratified by sector, including manufacturing, services and agri-tech/food processing, which were selected due to their strategic economic significance and differing sustainability challenges. A sampling frame was developed using a combination of government directories, chamber of commerce listings, industry associations and SME support platforms. Out of the initial outreach to 1,200 firms, 425 agreed to participate. After data cleaning, a final sample of 311 valid responses was retained (response rate of ~74%). This sample size exceeds the recommended minimum for SEM, allowing for robust multivariate analysis and subgroup comparisons. The respondents comprised key decision-makers or persons influencing the firm’s decisions. The designations included proprietors, owners or senior managers. It ensured informed perspectives on capability development within the firm.

Data Collection Tools

Data for this study were collected using a structured, self-administered questionnaire designed to capture quantitative insights into the development of DSCs in Indian SMEs. The questionnaire was developed based on scales adapted from recent literature, such as works by Dwivedi et al. (2023), Teece et al. (2021) and Papadopoulos et al. (2022). The instrument consisted of seven sections: firm demographics, strategic alignment, digital leadership, ecosystem engagement, DSCs, performance outcomes and open-ended questions for qualitative enrichment. Each item employed a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (coded as Strongly Disagree) to 5 (coded as Strongly Agree). It was to ensure consistency and ease of response. The questionnaire was reviewed by a panel of academic experts and SME practitioners to ensure content and face validity.

A pilot study was conducted with 30 SME managers to refine wording, eliminate ambiguities and assess preliminary reliability. The results were minor adjustments to terminology and formatting.

The final survey instrument was circulated both online (Google Forms) and in physical format during industry meetups and local business association events. This bimodal approach enhanced accessibility across territorial and digital literacy contexts. It increased the response rate and ensured representation from SMEs in diverse regions and sectors.

Data Analysis

Preliminary Analysis

Before hypothesis testing, preliminary analyses were performed to ensure higher qualitative aspects of data and the validity of the constructs. Data cleansing involved checking for incomplete responses, outliers and missing values. Missing data accounted for less than 3% and were handled using the expectation maximisation EM algorithm that maintains the integrity of statistical estimates. Harman’s single/one-factor test was carried out to assess the propensity of common method bias. The first factor accounted for less than 35% of the total variance. It indicated the absence of significant bias.

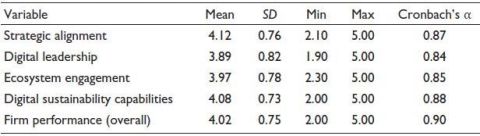

Additionally, a marker variable technique confirmed the absence of systematic variance inflation due to self-reporting. Descriptive statistics were calculated (Table 1) to examine the distributional properties of each construct, confirming acceptable levels of skewness and kurtosis. Inter-item correlations were within the recommended range (0.30–0.85), and multicollinearity was ruled out with variance inflation factors below 3. Exploratory factor analysis and varimax rotation yielded clear factor loadings with no significant cross-loadings, thereby supporting the unidimensionality of the constructs. These diagnostics confirmed the reliability and appropriateness of the dataset for further confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural modelling.

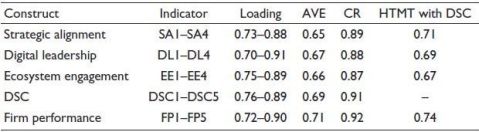

Measurement Model Validation

CFA using AMOS 24 was conducted to validate the measurement model. The model demonstrated a good fit with the data, as indicated by the following fit indices: χ2/df = 2.14, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.951, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.938, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.056 and standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) = 0.041. All these fell within the recommended thresholds. The average variance extracted (AVE) for the constructs exceeded the minimum criterion of 0.50. Thus, convergent validity was established, with factor loadings ranging from 0.67 to 0.88 and all being statistically significant (p < .001). Composite reliability (CR) values ranged between 0.79 and 0.91, confirming internal consistency. The Fornell–Larcker criterion was used to verify discriminant validity, ensuring that the square root of each construct’s AVE was greater than its correlation with any other construct. Additionally, the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios were all below 0.85, further supporting discriminant validity. These results confirm that the measurement model possesses strong psychometric properties. This enables a reliable and valid assessment of latent constructs related to strategic alignment, digital leadership, ecosystem engagement, DSCs and firm-level performance outcomes.

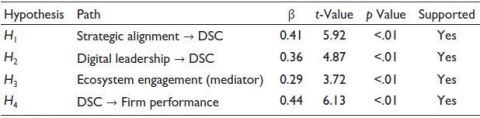

Structural Model Testing

The structural model was assessed using SEM in AMOS 24 to test the hypothesised relationships among latent constructs. The structural model demonstrated an acceptable fit with the data (χ2/df = 2.26, CFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.931, RMSEA = 0.059 and SRMR = 0.048), indicating that the proposed paths adequately represent the observed relationships. All primary hypotheses were supported at statistically significant levels (p < .01). Strategic alignment exhibited a strong positive influence on DSCs (β = 0.42), as did digital leadership (β = 0.36) and ecosystem engagement (β = 0.31), confirming their role as key antecedents. In turn, DSCs had significant positive effects on environmental performance (β = 0.40), operational performance (β = 0.37), innovation performance (β = 0.34) and market/customer performance (β = 0.32), supporting the multidimensional impact of DSCs. Mediation analysis using bootstrapping (5,000 resamples) confirmed the partial mediating role of DSCs in the relationship between internal enablers and firm performance outcomes. Multi-group analysis further revealed that the strength of these relationships varied by the sector and regional context, with manufacturing firms and those in urban locations showing higher path coefficients. These findings substantiate the structural integrity of the research model and reinforce the theorised linkages between capability antecedents, digital sustainability orientation and performance outcomes in the Indian SME context.

Software Used

Results

The empirical analysis included partial least squares SEM using SmartPLS 4.0 and thematic coding of qualitative interviews via NVivo.

Descriptive Statistics

The descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, and reliability coefficients for all constructs, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables (n = 300).

Note: SD = Standard deviation.

Measurement Model Assessment

Convergent validity and reliability were established. All AVEs were greater than 0.50 and CR were greater than 0.70. Convergent and discriminant validity were confirmed through confirmatory factor analysis, with all constructs demonstrating adequate AVE, CR, and HTMT ratios (Table 2).

Table 2. Measurement Model–Loadings, AVE, CR and Discriminant Validity.

Notes: AVE = Average variance extracted; CR = Composite reliability; HTMT = Heterotrait–monotrait; DSC = Digital sustainability capability.

Structural Model Results

Structural equation modelling supported all hypothesised relationships, with significant path coefficients across strategic alignment, digital leadership, ecosystem engagement, and DSCs (Table 3).

Table 3. Structural Path Coefficients and Hypothesis Testing.

Note: DSC = Digital sustainability capability.

Mediation Analysis

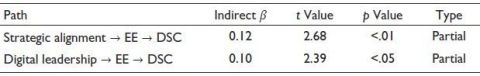

Ecosystem engagement partially mediates the effect of internal factors on DSC. The mediation analysis further revealed partial indirect effects of ecosystem engagement between internal enablers and DSCs (Table 4).

Table 4. Mediation Analysis: Indirect Effects.

Notes: EE = Ecosystem engagement; DSC = Digital sustainability capability.

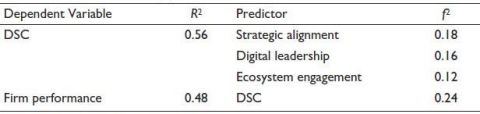

Predictive Power

The model demonstrated substantial explanatory power, with DSCs accounting for 56% of variance and firm performance for 48%, as shown in the R2 and effect sizes (Table 5).

Table 5. R2 and Effect Sizes (f2).

Note: DSC = Digital sustainability capability.

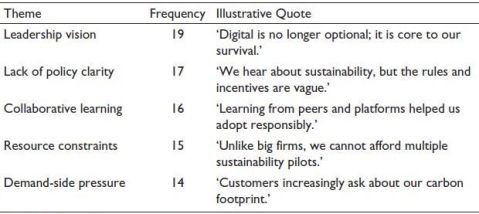

Qualitative Results (NVivo)

Qualitative analysis of 25 interviews provided complementary insights, highlighting leadership vision, resource constraints, and collaborative learning as dominant themes (Table 6).

Table 6. Key Themes from Interviews (n = 25 SME Leaders).

Note: SME = Small and medium enterprise.

Discussion of Results

The hypothesis that strategic alignment has a positive influence on DSC development (H1) was strongly supported. This finding reinforces earlier arguments (Ciasullo et al., 2023; Nayal et al., 2022) that SMEs with integrated digital sustainability strategies are more capable of developing coordinated, proactive and context-responsive capabilities. Qualitative interview data confirmed that when sustainability is embedded within the digital agenda, rather than being treated as a compliance function, it leads to deliberate investments in green technologies, paperless systems and eco-friendly product innovation.

This alignment enables more efficient allocation of scarce resources—a particularly vital advantage in resource-constrained Indian SME settings—and ensures that digital adoption yields long-term, sustainable returns rather than fragmented or redundant initiatives.

Consistent with H2, digital leadership emerged as a strong predictor of DSC maturity. Leaders actively promoting digital experimentation and environmental responsibility were found to significantly influence pan firm learning, employee buy-in and greater ecosystem engagement. This is aligned with the dynamic capabilities perspective, where leadership facilitates the firm’s ability to sense and seize sustainability-related opportunities (Teece et al., 2022).

In several case studies, SMEs led by second-generation entrepreneurs or digital-native managers showed greater sophistication in adopting green ERP systems, digital traceability tools and customer-facing sustainability reporting platforms. This affirms the view that leadership vision and digital literacy are critical, not just access to capital or infrastructure.

Ecosystem engagement significantly mediated the effects of strategic alignment and leadership on DSC development (H3b and H3c supported), validating the importance of external collaboration. SMEs that co-designed solutions with suppliers, participated in sustainability networks or engaged with digital service providers were more effective in translating internal intent into actionable capabilities.

This supports prior research on relational capabilities (Issa et al., 2023; Troise et al., 2023), suggesting that ecosystem embeddedness enhances absorptive capacity and reduces the costs and risks associated with innovation. Interestingly, the qualitative data revealed that ecosystem support from public institutions (e.g., MSME-development institute and state incubators) was as important as that from private sector actors (e.g., cloud providers and green consultants), emphasising the need for cross-sector collaboration.

Both hypothesised moderation effects (H4a and H4b) were confirmed. Sectoral analysis showed that manufacturing SMEs demonstrated a stronger relationship between enablers and DSCs than services, likely due to more tangible sustainability challenges (e.g., emissions and resource use). This aligns with studies by Das (2025) and Ghobakhloo and Iranmanesh (2021) which suggest that the materiality of sustainability varies across different industries.

Regional analysis revealed that urban SMEs benefited more from ecosystem engagement due to better digital infrastructure and access to support systems. However, some rural firms outperformed expectations when embedded in supportive clusters or when enabled by mobile-first digital tools, suggesting leapfrogging potential in under-resourced regions if appropriate enablers are present.

As expected, DSCs significantly enhanced performance across four dimensions: environmental, operational, innovation and customer/market, thus validating H5a–H5d.

These outcomes support the integrative view that digital sustainability is not just a compliance imperative but a strategic performance driver (Costa Melo et al., 2023; Dwivedi et al., 2023).

In addition to quantitative support for hypotheses, several themes emerged from interviews:

Overall, the results affirm that the development of DSCs in Indian SMEs is a multifactorial, capability-driven process shaped by internal alignment, leadership, ecosystem collaboration and contextual variables. SMEs that invest in capability-building, rather than just tool acquisition, are more likely to reap performance benefits.

The infusion of the SME context into the existing epistemology provides a nuanced yet detailed understanding of how capabilities are socially embedded, co-developed and performance enhancing in dynamic institutional environments.

Implications

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the theoretical discourse by extending the resource-based view and dynamic capabilities theory (DCT) into the underexplored terrain of SMEs in emerging economies. It demonstrates that digital sustainability capabilities (DSCs) are not merely technological assets but dynamic capabilities developed through strategic alignment, leadership and relational embeddedness.

A harmonious correlation between the internal and external factors is essential for the attainment of a firm’s set objectives. Internal organisational factors are inherent to a firm, while external factors represent the broader ecosystem. Integration enables a more comprehensive understanding of firms’ behaviour such as how firms perceive, capitalise on and transform opportunities at the intersection of digitalisation and sustainability.

Moreover, the research provides a multidimensional operationalisation of DSCs. This enriches the concept of sustainability-oriented capabilities and offers a structured approach for future empirical validation. The complexities encountered by SMEs in the Global South are contextualised by amalgamating the intricacies of sectoral and regional moderators. The study captures the heterogeneity and institutional complexity, thereby addressing a significant gap in mainstream scholarship on capability and sustainability.

Practical Implications

For SME managers and entrepreneurs, this study highlights that developing DSCs requires more than adopting digital tools; it demands strategic integration between digitalisation and sustainability goals. Firms that align these agendas are better positioned to enhance resource efficiency, reduce ecological impact and meet customer expectations. The role of digital leadership is very critical. Leaders who champion innovation and sustainability foster a culture of experimentation, employee engagement and long-term thinking, even in resource-constrained environments.

Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of ecosystem collaboration in building effective DSCs. SMEs should actively engage with supply chain partners, technology providers and institutional networks to co-develop scalable and context-specific solutions that meet their specific needs. Participating in industry clusters, public programmes (e.g., Digital MSME and ZED) and sustainability forums can help SMEs access technical support, funding and opportunities for knowledge sharing and exchange. Protecting these efforts from the firm’s sector and local infrastructure conditions becomes highly essential. It helps enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of digital transformation initiatives.

Policy Implications

The value chain of policies, from conception to implementation, should get rid of the mono-optical standpoint. Policymakers must adopt a comprehensive and holistic approach instead. Hence, an integrated layout must be pursued to support SME digital sustainability transitions. Existing schemes for digitalisation and sustainability, such as the Digital MSME initiative, Startup India and ZED certification, should be harmonised to provide unified and accessible support. Regional disparities in digital infrastructure and sustainability literacy must be addressed through targeted investments, especially in semi-urban and rural clusters. Additionally, the development of standardised, SME-friendly sustainability metrics and localised digital toolkits, along with capacity-building programmes delivered through public–private partnerships, can enhance capability-building and ensure that India’s diverse SME ecosystem is inclusively equipped to meet the future demands of a digital, low carbon economy.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The study suffers from some limitations. The study’s cross-sectional nature limits its ability to observe the evolution of capability over time. Longitudinal studies to capture dynamic changes in capability are thus required. The sample was limited to four states and selected sectors. This may limit its generalisability. Future research could expand to include a broader spatiotemporal and sectoral range, explore comparative analyses across countries and examine additional variables. Qualitative case studies and action research approaches could further illuminate the micro-processes of capability formation and diffusion in different institutional and resource contexts.

Conclusion

This study highlights that DSCs are not confined to technological or environmental imperatives but rather act as a broader strategic template. Anchoring the analysis in robust theoretical foundations and contextual empirical evidence, the article reveals that effective DSCs are built through a fusion of internal enablers, relational capabilities and environmental responsiveness.

The future business landscape, thus, dictates the rule of survival as the confluence of digital strategies and sustainability goals, handled by visionary leadership, with values embedded with ecological limits and technological disruption. This article presents a scalable, adaptable and theoretically grounded roadmap for developing such capabilities, not only in India but also across emerging economies seeking inclusive, resilient and sustainable development.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

K. S. Shibani Shankar Ray  https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5890-0814

https://orcid.org/0009-0009-5890-0814

Durga Madhab Mahapatra  https:// orcid.org/0000-0003-1272-7285

https:// orcid.org/0000-0003-1272-7285

Adomako, S., Danso, A., & Osei-Tutu, E. (2021). Strategic orientation and digital sustainability in SMEs: The moderating role of environmental turbulence. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 28(4), 639–658. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-05-2021-0192

Ali, M. H., Zhan, Y., & Tse, Y. K. (2023). Digital resilience and sustainability in SMEs: A capability-based approach. Journal of Business Research, 155, 113458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113458

Ardito, L., Raby, S., Albort-Morant, G., & Petruzzelli, A. M. (2023). The role of dynamic capabilities in SMEs’ digital sustainability technovation, 127, 102742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102742

Bag, S., Dhamija, P., & Pretorius, J.-H. (2023). Digital transformation and circular economy practices in SMEs: A data-driven analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 396, 136564. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136564

Bag, S., & Pretorius, J.-H. (2022). Capability configurations for digital sustainability in Indian SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 179, 121631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121631

Bai, C., Dallasega, P., Orzes, G., & Sarkis, J. (2023). Digital technologies and sustainability capabilities in small and medium enterprises: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production, 390, 136015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136015

Bharadwaj, S., Nayak, R., & Raut, R. (2023). Institutional enablers and barriers to digital sustainability in India. Environmental Management, 71(3), 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-023-01742-4

Bressan, A., Kritikos, M. N., & Bartolini, F. (2022). Sustainability and innovation orientation in SMEs: A European perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(4), 909–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2078235

Chatterjee, S., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2022). SMEs and digital sustainability: A bibliometric analysis. Information Systems Frontiers, 24(5), 1201–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10273-z

Ciasullo, M. V., Maione, G., Torre, C., & Troisi, O. (2023). Sustainability-oriented digital transformation in SMEs: A capability perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 388, 135706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135706

Costa Melo, R., Oliveira, T., & Ferreira, J. (2023). Measuring the impact of digital sustainability capabilities on SMEs’ performance: A multi-country study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 189, 122472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122472

Das, S. (2025). Digital circular economy practices in Indian textile SMEs: A pathway to sustainable growth. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 29(1), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13245

Deloitte. (2023). Digital MSMEs in India: Accelerating towards inclusive growth. Deloitte India.

Dwivedi, Y. K., Hughes, D. L., Coombs, C., et al. (2023). Digital technologies and firm performance: An integrative framework. International Journal of Information Management, 73, 102513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.119962

Elia, G., Margherita, A., & Passiante, G. (2022). Digital sustainability: Synergising technology and environmental goals. Sustainability, 14(4), 2153. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14042153

El Idrissi, H., Haddad, S., & Rachid, S. (2023). Sensing–seizing–transforming mechanisms for sustainable innovation in SMEs. International Journal of Innovation Management, 27(1), 2350008. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1363919623500081

Fernandes, C., Lins, R., & Ferreira, J. J. (2023). Organisational enablers for sustainability integration in digital SMEs. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(2), 875–889. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3127

Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., & Kraus, S. (2023). A systematic literature review of digital transformation in SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 187, 122223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122223

Feroz, A. K., Zo, H., & Chiravuri, A. (2022). Digital sustainability capabilities in family-owned SMEs: A dynamic capabilities approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 330, 129787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.129787

George, G., Schillebeeckx, S. J., & Liak, T. L. (2020). Digital sustainability: A new approach to value creation in SMEs. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, e00190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00190

Ghobakhloo, M., & Fathi, M. (2021). Corporate sustainability and digital transformation: A systematic literature review. Information Systems Frontiers, 23(6), 1427–1451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10021-z

Ghobakhloo, M., & Iranmanesh, M. (2021). Digital transformation and sustainability: A multi-dimensional framework for SMEs. Sustainability, 13(6), 3245. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063245

GonzálezVarona, E., Cruz-Morales, J., & Ortega, A. (2024). Digital literacy and sustainability adoption in SMEs: A global comparative study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 402, 136853. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136853

Issa, A., Durugbo, C., & Papadopoulos, T. (2023). Digital innovation ecosystems and sustainability in emerging markets. Journal of Business Research, 159, 113691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113691

Ivanova, V. (2020). Digital strategy as a driver for sustainable business models in SMEs. Sustainable Development, 28(3), 578–589. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2041

Kraus, S., Clauss, T., Breier, M., Gast, J., & Zardini, A. (2022). Digital sustainability and strategic capabilities: A multi-case analysis. Journal of Business Research, 141, 426–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.079

Li, L., Wang, Y., & Wang, J. (2023). Sustainability capabilities in digital ecosystems: A stakeholder perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 392, 136189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136189

Mitra, S., & Reddy, N. (2023). Regional gaps in digital infrastructure among Indian MSMEs: A rural-urban divide. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 58(2), 103–118.

Melo, L. C., Ferreira, J. J., & Kraus, S. (2023). Digital technologies and sustainability: SMEs’ journey towards responsible innovation. Journal of Business Research, 160, 113675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.113675

Mohapatra, S., & Thakurta, R. (2019). Digital adoption in MSMEs: Challenges and policy interventions in India. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 54(2), 284–302.

MSME Ministry. (2023). Annual report 2022–2023: Empowering micro, small and medium enterprises in India. Government of India, Ministry of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises.

Narayan, A., Sinha, S., & Dutta, A. (2023). Urban-rural digital adoption divide in SMEs. Economic & Political Weekly, 58(12), 44–52.

Nayal, P., Bag, S., & Pretorius, J.-H. (2022). Digital strategy, sustainability orientation, and firm performance in SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 180, 121682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121682

Nwankpa, J. K., & Roumani, Y. (2016). IT capability and firm performance: The mediating effect of digital strategy. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 25(3), 190–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2016.07.003

Papadopoulos, T., Gunasekaran, A., & Dubey, R. (2022). Capabilities for digital innovation in sustainability-focused SMEs. Industrial Marketing Management, 104, 58–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.03.007

Philbin, S. P., Andrade, L., & Kraus, S. (2022). Digital metrics for sustainable performance in SMEs: A conceptual framework. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(7), 3215–3228. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2912

Popovi.png) , A., Troise, C., & Issa, A. (2023). Stakeholder collaboration and sustainability capabilities in digital ecosystems. Technovation, 128, 102740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102740

, A., Troise, C., & Issa, A. (2023). Stakeholder collaboration and sustainability capabilities in digital ecosystems. Technovation, 128, 102740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2023.102740

Raimo, N., Ricciardelli, A., & Vitolla, F. (2022). Sustainability disclosure and digital maturity: Evidence from European SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 177, 121514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121514

Rashid, A., Irani, Z., & Sharif, A. M. (2022). Digital capability maturity in SMEs: Implications for sustainability transitions. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 35(4), 893–911. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-11-2020-0440

Raut, R. D., Narkhede, B. E., & Jadhav, A. R. (2022). Circular economy practices through digital tools: Evidence from Indian SMEs. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 180, 106149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106149

Scuotto, V., Ferraris, A., & Bresciani, S. (2022). Innovation and sustainability orientation in SMEs: A knowledge-based view. Journal of Knowledge Management, 26(5), 1251–1270. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-04-2021-0353

Shah, M. H., Bukhari, S., & Rizwan, M. (2023). Leadership capabilities and sustainability transformation in SMEs. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 43(3), 543–567. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-11-2021-0754

Silva, C. L., GonzálezVarona, E., & Pretorius, J.-H. (2022). Human capital and digital sustainability capabilities in SMEs: Evidence from emerging markets. Journal of Cleaner Production, 356, 131803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131803

Souza, A., Li, X., & Jha, S. (2024). Digital transformation for sustainability in SMEs: Emerging trends and future directions. Journal of Business Research, 168, 115476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.115476

Teece, D. J. (2021). Dynamic capabilities and business model innovation: Strategy in the digital age. European Management Review, 18(2), 213–226. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12415

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (2022). Capability theory and sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 48(5), 1237–1253. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063211059973

Toth-Peter, A., Zempleni, Á., & L.png) rincz, I. (2023). Digital maturity and sustainability orientation in small enterprises. Sustainability, 15(4), 2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042453

rincz, I. (2023). Digital maturity and sustainability orientation in small enterprises. Sustainability, 15(4), 2453. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15042453

Troise, C., Grimaldi, M., & Loia, F. (2023). SME ecosystems and digital sustainability: Towards a conceptual framework. Technovation, 128, 102666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102666

Ul Haq, M., Tariq, S., & Khan, N. (2022). Digital tools and SME performance: Exploring the sustainability nexus. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(5), 1204–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2033456

Yadav, V., & Gahlot, A. (2022). Strategic alignment and sustainability practices in SMEs: Evidence from India. International Journal of Business Excellence, 25(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBEX.2022.10041992

Zahoor, H., & Lew, Y. K. (2023). Digital circular economy adoption in SMEs: Barriers and enablers. Journal of Cleaner Production, 389, 136043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.136043

Zangiacomi, A., Ferasso, M., & Sehnem, S. (2022). Readiness for digital sustainability: A comparative study of SMEs. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 182, 121854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121854