1Faculty of Management, JIS University, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

2Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences, University of Southampton, UK

3Department of Tourism Management, The University of Burdwan, West Bengal, India

4Department of Commerce, The University of Calcutta, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

5Department of Management Studies, Asansol Engineering College, Asansol, West Bengal, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This study investigates how ambient conditions, specifically lighting, scent, music, and temperature, affect customer satisfaction in Indian urban restaurants. Grounded in Bitner’s servicescape model and the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework, the research aims to measure expectation–perception gaps across these sensory dimensions and assess their impact on overall satisfaction. A structured survey was administered to 250 respondents using a 5-point Likert scale to capture both expectations and perceptions of ambient conditions. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a nonparametric method suitable for ordinal data, was applied to examine significant differences between expectation and perception scores for each factor. Results reveal statistically significant differences across all four ambient variables. Lighting, scent, and music exceeded customer expectations, indicating positive disconfirmation and enhanced satisfaction. Conversely, temperature fell short of expectations, highlighting discomfort as a key dissatisfaction driver. The findings affirm that ambient cues are not peripheral but central to shaping experiential quality in hospitality settings. This study contributes by integrating servicescape and S-O-R theories with a nonparametric statistical approach to empirically test expectation–perception gaps in an Indian context. It highlights dimension-specific insights, offering actionable guidance for restaurant managers to refine sensory strategies for competitive advantage.

Servicescape, S-O-R Model, Consumer Satisfaction, Consumer Expectation and Perception

Introduction

In today’s competitive hospitality industry, the differentiation of services extends beyond culinary excellence into sensory and experiential design. The servicescape coined by Bitner (1992) refers to the physical and atmospheric environment that subtly but powerfully influences customer behavior. This includes lighting, scent, music, and thermal comfort. Drawing on the stimulus–organism–response (S-O-R) framework, which explains how environmental stimuli elicit emotional and behavioral responses, this study aims to quantify the contribution of each ambient variable. Recognizing the limitations of linear regression in dealing with ordinal data and potential nonnormal distributions, we incorporate the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to examine perceived changes in customer satisfaction associated with each environmental factor. In the increasingly competitive restaurant industry, a comprehensive understanding of the determinants of customer satisfaction has become essential. While food quality and service excellence remain critical, emerging scholarship emphasizes the importance of the servicescape, the physical and sensory environment in which services are delivered, as a key driver of customer experience. The concept of servicescape, introduced by Bitner (1992), encompasses the physical surroundings that influence customer expectations, perceptions, and behaviors within service settings. Among its core dimensions, ambient conditions including lighting, temperature, scent, and background music play a particularly influential role in shaping customers’ affective and cognitive evaluations of their dining experiences.

These ambient elements form the sensory backdrop of the dining environment and exert a largely subconscious yet powerful effect on customer moods and perceptions. They significantly contribute to how individuals assess service quality and overall satisfaction, especially in urban restaurant settings where experiential quality increasingly differentiates service offerings. In this evolving landscape, restaurants are no longer evaluated solely on culinary performance; rather, experiential immersion shaped by thoughtfully curated sensory stimuli is a central aspect of competitive positioning. The theoretical foundation for understanding this dynamic lies in the S-O-R framework proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974). This model posits that environmental stimuli (e.g., music or scent) impact the organism (i.e., the customer) by eliciting emotional and cognitive responses, which in turn influence behavioral outcomes such as satisfaction, loyalty, and word-of-mouth behavior. Within the context of restaurant services, ambient stimuli can be strategically manipulated to positively shape the emotional tone of the dining experience, ultimately enhancing consumer satisfaction and long-term engagement. Despite growing recognition of the servicescape’s relevance, there is a notable dearth of empirical research that quantitatively measures the impact of ambient conditions on customer satisfaction, particularly in emerging markets such as India. While conceptual discussions and anecdotal evidence abound, few studies employ rigorous statistical techniques such as regression or nonparametric tests to isolate and evaluate the effects of specific ambient attributes. Furthermore, the interaction effects among multiple sensory elements, for example, how lighting might alter the perception of scent, or how temperature may moderate music’s influence, remain insufficiently examined. Urban Indian restaurants, especially those located in Orissa and Kolkata, provide an ideal setting for such empirical inquiry. These restaurants operate within complex socio-cultural environments and cater to a demographically diverse clientele. Moreover, these urban spaces are shaped by regional climatic variability, spatial constraints, and evolving consumer expectations, making them fertile ground for analyzing how ambient design elements influence satisfaction across different customer segments. In response to these research gaps, the present study adopts a robust quantitative approach to examine the differential impact of lighting, scent, temperature, and music on customer satisfaction in Indian urban restaurants. By anchoring the analysis within the servicescape and S-O-R frameworks, this research not only contributes to the growing body of knowledge in hospitality and service marketing but also offers practical insights for restaurant managers seeking to enhance experiential value through sensory design strategies.

Literature Review

According to the “social-servicescape model” put forth by Tombs and McColl-Kennedy (2003), consumer behavior is influenced by both the social and physical aspects of the environment, including other customers and service providers. “The design of the physical environment and service staff qualities that characterize the context which houses the service encounter, which elicits internal reactions from customers leading to the display of approach or avoidance behaviors” is the term used to describe the servicescape by Bitner (1992). In conclusion, it has been said that the servicescape consists of both tangible and intangible components, such as contextual, social, and psychological features. Within the servicescape literature (Areni & Kim, 1993; Baker et al., 1992; Dubé et al., 1995; North et al., 1999; Yalch & Spangenberg, 1988, 1990). The customers’ behavioral intentions and level of satisfaction are influenced by numerous factors. The majority of the research has been on the service organization’s interior physical appearance, including its furnishings, décor, lighting, music, odor, color, and so forth. The next section provides a quick overview of earlier servicescape research. A single environmental stimulus does not determine a customer’s assessment of a specific service. Generally speaking, customers evaluate servicescapes holistically and consider a variety of factors when determining how satisfied they are (Bitner, 1992; Lin, 2004). Customers’ holistic views (i.e., perceived quality) and subsequent internal (i.e., contentment with the servicescape) and external (i.e., approach/avoidance, remaining, resupport) responses are influenced by the primary characteristics of the servicescape, according to Bitner (1992). Lin and Mattila (2010) state that customers consider both the servicescape and interactions with employees when evaluating service experiences. According to research, music has a significant role in servicescapes because it evokes strong feelings, influences customers’ perceptions, moods, and purchasing decisions (Areni & Kim, 1993) and affects their level of relaxation and contentment (Ryu & Han, 2010). According to studies done in hotels and restaurants, the tempo of the music can influence how quickly people shop, how long they stay, and how much money they spend. Furthermore, loudness and noise typically have a negative impact on customers. People have said that noise is disagreeable and bothersome (Kryter, 1985). One element that might be disagreeable if not properly managed is temperature. Customers may feel negatively about an environment that is too hot or cold (Medabesh & Upadhyaya, 2012). A consumer’s urge to buy can be influenced by scent or odor. “Pleasant scents encourage customers to spend more time in the servicescape,” determined Morrin and Ratneshwar (2003). According to Hirsch’s (1991) research, bakeries can boost sales by 300% by using scent strategically. In the service setting, coffee chains such as Starbucks place a lot of attention on scent (Hunter, 1995). According to research, one of the most potent physical triggers in restaurants can be the lighting. People’s emotional reactions and their preferred lighting levels are related; for example, bright lighting at fast-food restaurants (like McDonald’s) may represent prompt service and reasonably priced food. Conversely, dim illumination could represent complete service and expensive costs (Ryu & Han, 2010). Because it provides customers with implicit cues about the standards and expectations for behavior in the servicescape (Bitner, 1992), décor—the caliber of materials used in construction, artwork, and floor coverings is a visual symbol used to create an appropriate atmosphere within the servicescape (Nguyen & Leblanc, 2002). In the social context of a restaurant, décor is significant because it influences human behavior, especially social intimacy (Gifford, 1988). Similar to this, a customer’s perception of a restaurant’s success or failure, price or affordability, and reliability can all be influenced by its décor (Bitner, 1992; Nguyen & Leblanc, 2002). Customers’ perceptions of quality and enthusiasm levels may be directly impacted by furnishings, and their willingness to return may be indirectly impacted (Ryu & Han, 2010). Customers’ comfort levels and opinions of the quality of the service are influenced by the furnishings in a restaurant (Arneill & Devlin, 2002; Baker, 1987; Bitner, 1992). Wakefield and Blodgett (1996, p. 54) point out that as “customers remain in the same seat for extended periods of time,” comfort becomes crucial. One important aspect of the service environment has been identified as cleanliness (Turley & Milliman, 2000). Customers’ satisfaction levels and perceptions of service quality are impacted (Wakefield & Blodgett, 1996). It affects how consumers perceive the service at first and, consequently, whether they plan to use it again (Harris & Sachau, 2005). Basic contentment results from expectations being confirmed when cleanliness meets expectations. Positive disconfirmation and positive emotions occur when servicescape cleanliness surpasses initial expectations (Vilnai-Yavetz & Gilboa, 2010). According to a study by Hoffman et al. (2003), consumers blamed servicescape failures on unclean rooms and other areas. Customer retention rates were lowest for businesses with the worst cleanliness issues. Lucas (2003) discovered a correlation between a casino’s cleanliness and its patrons’ pleasure with the service, willingness to promote it, intention to return, and desire to stay. In their study, Vilnai-Yavetz and Gilboa (2010) discovered that cleanliness influences patrons’ inclination to return to the restaurant and is a significant predictor of approach behavior. According to Eiseman (1998), color is a powerful visual element of an interior environment. Color has been found to influence people’s emotions and moods. Brightly colored walls and seats may be more visually appealing than dull facades and seats (Tom et al., 1987). As a result, at a restaurant, the appropriate color schemes will either energize or calm patrons. Superior table décor, including glasses, cutlery, flatware, and table coverings, can affect how patrons see the entire caliber of restaurant service. Additionally, table décor (such as candles and fresh flowers) might give patrons the impression that they are in a fine dining establishment. A restaurant’s spatial arrangement, including the placement of the service areas, restrooms, entry, doors, and corridors, is crucial. In service areas that are easily accessible, customers might spend more time. This could raise the probable amount of money they spend. Time and money spent in hotels are positively correlated, according to research in the hotel industry (O’Neill, 1992). Communication can be greatly aided by signage that subtly conveys to patrons the restaurant’s image, standards, and anticipated conduct. The perceived quality of the servicescape may also be improved by additional interior design elements such as banners, photos, ornamental signs, and other fixtures. Service presentation is associated with the staff’s demeanor, credentials, and conduct. Employees in restaurants have a big impact on patrons’ opinions, intentions to buy, and loyalty. Customers’ opinions of a service are greatly influenced by the actions of frontline service providers (Lin & Mattila, 2010). The service experience can be substantially improved by the way the employees look (Baker, 1987, p. 81). According to Hutton and Richardson (1995, p. 59), a service organization’s image is largely shaped by the physical attractiveness of its employees, or “a pleasing physical demeanor through clean and colorful uniforms and proper personal grooming.” In their study, Vilnai-Yavetz and Gilboa (2010) discovered a favorable correlation between the customers’ perceptions of the waiter’s appearance and their sentiments of trust and friendliness. Customers’ initial perception of a restaurant and its offerings is shaped by its physical space. As a result, the restaurant’s layout, architecture, appearance, furnishings, and personnel all play a significant role in how guests perceive it right away; the restaurant’s servicescape is significant for customer experiences (McDonnell & Hall, 2008). Consumers evaluate the restaurant’s physical layout, external and interior features, and surroundings, all of which have an impact on patron satisfaction and enjoyment (Lin & Mattila, 2010). When customers evaluate the quality of a restaurant and the eating experience, the servicescape may also elicit cognitive or perceptual reactions (service quality, disconfirmation, value) in them (Kim & Moon, 2009). According to Reimer and Kuehn (2005), servicescapes have an impact on how long patrons want to stay at a restaurant and if they plan to return, which in turn affects how well they perceive the overall quality of the establishment. Customers may encounter a variety of cues in a service setting that could influence their behavior, purchases, and level of pleasure with the experience, according to Herrington (1996). Studies on how consumers react to servicescapes demonstrate that they serve as indicators for assessing the quality of services provided (Baker, 1987; Bitner, 1992). Customers’ purchasing decisions are influenced by the atmosphere, which includes things such as music, temperature, lighting, colors, and aroma (Kotler, 1973). Emotions are influenced by the restaurant’s ambiance since a pleasant ambiance heightens feelings of happiness. Positive feelings also raise client satisfaction. Furthermore, consumer happiness has a significant impact on behavioral loyalty. Customer satisfaction influences their future behavior since happy patrons are more likely to return, suggest the restaurant to others, eat there more frequently, spread the word about it, and be willing to pay more. The décor and artifacts, the layout, and the ambient conditions have a favorable correlation with the perceived value of the patrons, according to Han and Ryu (2009). Customers’ perceived value was a direct and positive antecedent of customer satisfaction, according to Patterson and Spreng’s (1997) analysis of the role of perceived value in explaining consumer behavior in a service setting. In their research on restaurants, Harris and Ezeh (2008) discovered that five aspects of the servicescape cleanliness, staff physical attractiveness, furnishing, customer orientation, and implicit communicators/aesthetic appeal were very influential in influencing patrons’ intentions to remain loyal. In 1981, Booms and Bitner developed the concept of servicescape to suggest the entirety of the physical state of the administrative underpinnings.

Objectives of the Study

Theoretical Framework

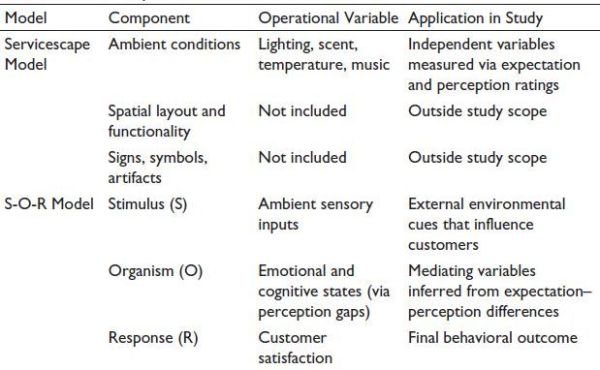

The hospitality industry, particularly the restaurant sector, has seen a paradigm shift where customer satisfaction is increasingly influenced not just by food and service quality, but by the physical and sensory elements of the service environment. In this context, Bitner’s (1992) servicescape model serves as a foundational framework. The model conceptualizes the physical environment as a significant variable influencing customer and employee behavior. It breaks down the servicescape into three dimensions: ambient conditions, spatial layout and functionality, and signs, symbols, and artifacts. For the purpose of this study, the focus is specifically on ambient conditions, including lighting, scent, temperature, and music, which are considered the most immediate and influential sensory cues in shaping customer perceptions and emotional responses in restaurant settings.

Ambient conditions, as conceptualized in the servicescape model, form the atmospheric backdrop that impacts customers at both conscious and subconscious levels. These sensory elements are particularly relevant in urban Indian restaurants, where intense competition has led establishments to invest heavily in experiential differentiation. A well-designed servicescape not only enhances aesthetic appeal but also affects how customers interpret service quality, comfort, and emotional well-being. However, the extent to which these ambient conditions meet or fall short of customer expectations has not been widely measured in empirical studies, especially in the Indian context. This research thus seeks to bridge this gap by comparing customer expectations and perceptions of these ambient features to evaluate their influence on satisfaction outcomes.

To interpret the psychological effects of the servicescape more comprehensively, this study also draws upon the S-O-R model proposed by Mehrabian and Russell (1974). According to this model, external environmental stimuli (S) affect internal emotional and cognitive states (O), which in turn produce observable behavioral outcomes (R), such as satisfaction, loyalty, or intent to return. In the restaurant setting, sensory stimuli such as lighting or scent serve as external cues, influencing a customer’s internal state, such as comfort, arousal, or pleasure, which then shapes their overall evaluation of the dining experience. The S-O-R model thus complements the servicescape framework by embedding customer psychology within the analysis of environmental influence.

This dual-framework approach provides both a structural and psychological lens to examine how restaurant environments affect satisfaction. While the servicescape model outlines what components to evaluate, the S-O-R model explains how and why these components influence behavior. Integrating these models enables a robust conceptual foundation for understanding the link between physical design and consumer experience. In this study, satisfaction is positioned as the final response (R), influenced by organismic states (emotions/perceptions) triggered by sensory stimuli (ambient conditions). The expectation–perception gap is treated as a proxy for these emotional and cognitive evaluations, thus grounding the methodology in well-established theoretical constructs. A distinctive feature of this study is its application of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to statistically assess the differences between expectations and perceptions across the four ambient dimensions. Unlike traditional regression approaches that assume normally distributed interval data, the Wilcoxon method is nonparametric and better suited for ordinal data derived from Likert scales. It also allows for paired comparisons in this case, between a customer’s anticipated experience and their actual experience, which aligns with the theoretical premise of the S-O-R framework. By identifying whether the gap between expectation and perception is significant for each sensory variable, the study operationalizes the servicescape and S-O-R models within a robust empirical strategy.

The integrated theoretical structure of this research is summarized in Table 1. Ambient conditions (lighting, scent, temperature, and music) are analyzed as stimuli in the S-O-R framework and as core environmental dimensions within the servicescape model. Customer emotions and perceptions, inferred through the difference between expectations and perceptions, serve as the organismic element. Finally, satisfaction is treated as the behavioral response demonstrating the combined influence of physical environment and psychological processing. This framework not only validates the relevance of sensory design in service environments but also provides a quantitative pathway for assessing its real-world impact.

Table 1. Tabular Representation of Theoretical Framework.

Analytical Framework

The sensory environment of a restaurant, commonly referred to as the servicescape, plays a critical role in shaping customer satisfaction. In the context of India’s urban hospitality sector, where competition is high and experiential quality is a key differentiator, understanding the gap between customer expectations and their actual perceptions becomes essential. To address this, we employed the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a nonparametric statistical method ideal for comparing paired samples from the same subjects (i.e., each respondent’s expectation vs perception). This analysis aims to evaluate the statistical significance of gaps across four ambient dimensions: lighting, scent, temperature, and music.

Methodology Overview

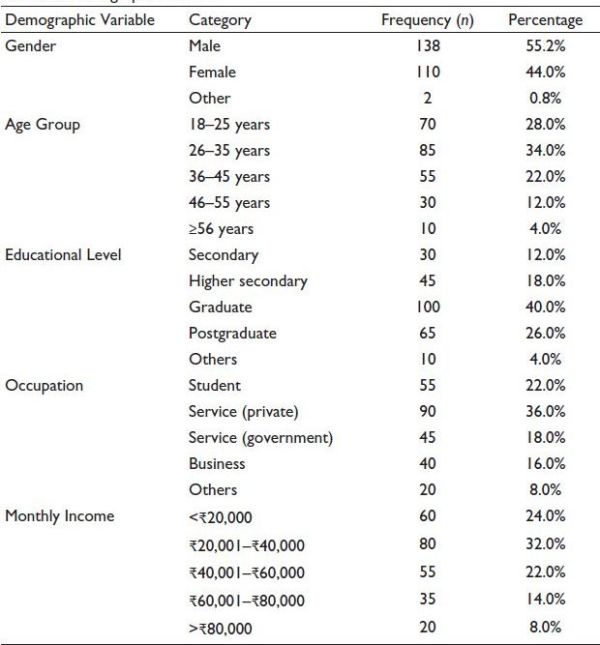

A sample of 250 respondents was surveyed, each providing ratings on a 5-point Likert scale for both expectation and perception related to each of the four ambient variables. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was chosen over parametric alternatives (e.g., paired t-test) due to the ordinal nature of the data and the absence of a guaranteed normal distribution. This test evaluates whether the median difference between expectation and perception scores is significantly different from zero.

Table 2. Demographic Profile.

The variables under scrutiny include:

Lighting: Visual atmosphere, brightness, and comfort.

Scent: Ambient fragrance or aroma associated with the dining space.

Temperature: Thermal comfort of the environment.

Music: Background sound and its congruence with the dining theme.

Hypotheses

H01: There is a significant difference between customers’ expectations and perceptions of lighting in urban restaurants.

H02: There is a significant difference between customers’ expectations and perceptions of scent in urban restaurants.

H03: There is a significant difference between customers’ expectations and perceptions of temperature in urban restaurants.

H04: There is a significant difference between customers’ expectations and perceptions of music in urban restaurants.

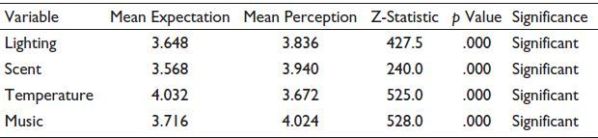

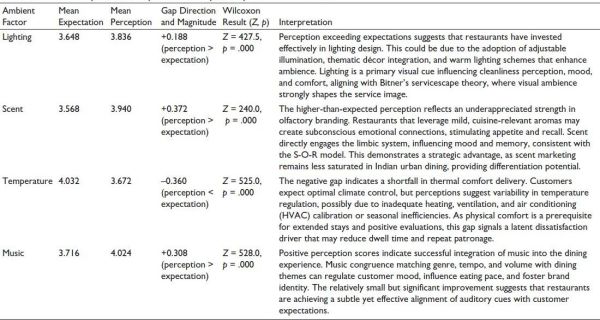

Table 3. Results of the Wilcoxon Signed-rank Test.

Based on Table 3, the following gaps have been observed as the outcomes of hypotheses:

H1a: Customers’ perceptions of lighting are significantly higher than their expectations.

H2a: Customers’ perceptions of scent are significantly higher than their expectations.

H3a: Customers’ perceptions of temperature are significantly lower than their expectations.

H4a: Customers’ perceptions of music are significantly higher than their expectations.

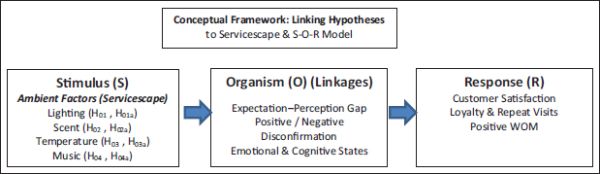

Theoretical Linkages to Servicescape and S-O-R

In the view of servicescape: It is depicted that ambient conditions are core drivers of evaluative judgments in hospitality environments. The heterogeneity of gaps suggests treating ambient conditions as distinct levers (not a monolith), each with different thresholds for guest satisfaction. S-O-R: Ambient stimuli (S) shape internal affective/cognitive states (O) that drive satisfaction and downstream behavior (R). Positive gaps in scent/music/lighting imply positive arousal and congruence, while the negative gap in temperature suggests aversive arousal that can suppress overall satisfaction even when other cues perform well.

Expectation–disconfirmation: Results exemplify positive disconfirmation (delight) for enhancement cues and negative disconfirmation (dissatisfaction) for temperature. Consistent with loss-gain asymmetry, shortfalls in comfort often weigh more heavily than equivalent exceedance in aesthetics. Methodological contribution: The Wilcoxon approach is appropriate for paired ordinal data, avoids normality assumptions, and centers interpretation on the median difference, a robust choice for Likert measures.

Based on Table 4, the Wilcoxon signed-rank analysis reveals a nuanced interplay between customer expectations and sensory experiences in Indian urban restaurants, with divergent patterns emerging across ambient factors.

Lighting emerged as a notable overperformer, with perceptions surpassing expectations by +0.188 points on a 5-point scale. This indicates that contemporary restaurants are succeeding in crafting visually appealing atmospheres, possibly through adaptive lighting schemes, use of warm tones, and integration with thematic décor. Within the servicescape model, lighting is recognized as a dominant environmental cue influencing affective and cognitive evaluations. A well-lit environment not only enhances aesthetic appeal but also contributes to perceptions of hygiene, service promptness, and overall ambience.

Figure 1. Linkages to Servicescape and S-O-R.

Scent recorded a perception gain (+0.372), marking it as the most improved dimension relative to expectations. Olfactory stimuli operate at a subconscious level, triggering emotional and mnemonic associations that can significantly enhance the dining experience. As theorized in the S-O-R framework, scent serves as a powerful external stimulus that shapes internal emotional states, leading to favorable behavioral outcomes such as increased dwell time and repeat visitation. The results imply that select urban Indian restaurants are effectively employing scent management either intentionally through aroma diffusion or indirectly through open-kitchen concepts, thus achieving a competitive edge.

In the context of temperature, a negative gap (–0.360) was presented, signifying that thermal comfort is a persistent operational challenge. Given India’s climatic diversity, this finding underscores the importance of adaptive climate control strategies. Even marginal deviations from the thermal comfort zone can detract from perceived service quality, as physical discomfort often overrides other positive sensory inputs. This supports Bitner’s assertion that ambient conditions serve as baseline qualifiers in the servicescape; when these are unsatisfactory, they can disproportionately impact overall evaluations.

Music showed a moderate positive shift (+0.308), suggesting that auditory ambience is being leveraged effectively to enhance dining experiences. While music tends to be less consciously evaluated compared to visual or tactile elements, its role in shaping mood, regulating the pace of service, and reinforcing brand identity is well established in hospitality literature. The statistically significant improvement in perceptions suggests that restaurants are increasingly curating playlists that align with their thematic positioning and customer demographics, thus enhancing experiential coherence (See Table 2).

Based on the above discussion, the analysis confirms that ambient conditions collectively exert a significant influence on customer satisfaction, with scent and music exceeding expectations, lighting performing reliably well, and temperature management emerging as an area for urgent operational attention. These findings not only validate the integrative use of the servicescape and S-O-R models in hospitality research but also provide actionable insights for practitioners aiming to refine sensory strategies for competitive advantage (See Figure 1).

Table 4. Detailed Interpretation of Expectation–Perception Gaps in Ambient Factors.

Theoretical Implications

The present analysis advances theoretical understanding in services marketing, environmental psychology, and hospitality management by empirically validating the integrated applicability of Bitner’s Servicescape Model (1992) and the S-O-R framework (Mehrabian & Russell, 1974) within the context of Indian urban restaurants.

First, the findings reinforce the core tenet of the servicescape model that ambient conditions are not peripheral but central determinants of customer evaluations. The statistically significant differences between expectation and perception for all four sensory dimensions (lighting, scent, temperature, and music) confirm that customers are highly sensitive to the physical and atmospheric environment, even in the presence of other service quality indicators such as food taste and staff behavior. The magnitude and direction of these gaps underscore that different ambient factors influence satisfaction in distinct ways, with scent and music often exceeding expectations, lighting performing reliably, and temperature lagging behind. This heterogeneity suggests the need for refining the servicescape model to incorporate dimension-specific performance thresholds rather than treating ambient conditions as a homogeneous construct.

Second, the study provides empirical grounding for the S-O-R model’s sequential pathway from external stimuli to internal emotional states to behavioral outcomes. The expectation–perception gap functions here as a proxy for organismic emotional and cognitive states, capturing the dissonance (negative gap) or positive disconfirmation (positive gap) experienced by customers. The positive gaps observed in scent and music indicate that positive sensory surprises can enhance affective states and elevate satisfaction, whereas the negative gap in temperature illustrates how sensory discomfort can undermine overall evaluations even when other conditions are favorable. This supports the argument that ambient cues operate through dual channels, both as independent contributors to satisfaction and as moderators of the perceived quality of other service attributes.

Third, the application of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a nonparametric method, contributes to methodological discourse in hospitality research by demonstrating that ordinal-scale sensory data should be analyzed using distribution-free statistical techniques. This methodological choice addresses the limitations of parametric tests in handling Likert-scale responses and highlights the importance of matching analytical tools to the data’s measurement properties, thereby enhancing the robustness of environmental psychology research.

Fourth, the results suggest an experiential asymmetry consistent with prospect theory whereby negative sensory disconfirmation (temperature discomfort) carries a stronger potential to diminish satisfaction than positive disconfirmation (pleasant scent or music) has to enhance it. This aligns with behavioral economics perspectives that losses loom larger than gains in shaping subjective evaluations. Integrating this principle into the servicescape and S-O-R frameworks could refine their predictive capacity by recognizing that sensory deficits may disproportionately influence overall service evaluations.

Conclusion

On the basis of the above study, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test provides strong empirical support for the argument that gaps between expectation and perception across sensory dimensions significantly affect satisfaction in Indian urban restaurants. This study not only quantifies the perceptual mismatch but also underscores the strategic importance of harmonizing the ambient environment to create holistic and satisfying customer experiences. Future research could incorporate demographic segmentation and emotion tracking technologies to further enrich the understanding of servicescape dynamics. Finally, the study extends the cultural contextualization of servicescape theory. Much of the existing literature is grounded in Western service environments, yet this research demonstrates that the foundational models remain relevant in an emerging market context like India, albeit with contextual nuances. For instance, the pronounced temperature gap highlights the climatic variability and infrastructural challenges of Indian cities, suggesting that environmental comfort factors may require greater weighting in tropical and subtropical hospitality contexts than in temperate climates.

ORCID iD

Nilanjan Ray  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6109-6080

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6109-6080

Areni, C. S., & Kim, D. (1993). The influence of background music on shopping behaviour: Classical versus top-40 music in a wine store. In L. McAlister & M. L. Rothschild (Eds), Advances in consumer research (Vol. 20, pp. 336–340). Association for Consumer Research.

Arneill, A. B., & Devlin, A. S. (2002). Perceived quality of care: The influence of the waiting room environment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 22(4), 345–360.

Baker, J. (1987). The role of the environment in marketing services: The consumer perspective. In J. A. Czepiel, C. A. Congram, & J. Shanahan (Eds), The service challenge: Integrating for competitive advantage (pp. 79–84). American Marketing Association.

Baker, J., Levy, M., & Grewal, D. (1992). An experimental approach to making retail store environmental decisions. Journal of Retailing, 68(4), 445.

Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71.

Dubé, L., Chebat, J., & Morin, S. (1995). The effects of background music on consumers’ desire to affiliate in buyer–seller interactions. Psychology & Marketing, 12(4), 305–319.

Duncan Herrington, J. (1996). Effects of music in service environments: A field study. Journal of Services Marketing, 10(2), 26–41.

Eiseman, L. (1998). Colors for your every mood. Capital Books.

Gifford, R. (1988). Light, décor, arousal, comfort, and communication. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 8(3), 177–189.

Han, H. S., & Ryu, K. (2009). The roles of the physical environment, price perception, and customer satisfaction in determining customer loyalty in the family restaurant industry. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 33(4), 487–510.

Harris, L. C., & Ezeh, C. (2008). Servicescape and loyalty intentions: An empirical investigation. European Journal of Marketing, 42(3/4), 390–422.

Harris, P. B., & Sachau, D. (2005). Is cleanliness next to godliness? The role of housekeeping in impression formation. Environment and Behavior, 37(1), 81–101.

Hirsch, A. R. (1991, October). Nostalgia: A neuropsychiatric understanding. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Consumer Research.

Hunter, B. T. (1995). The sales appeals of scents (Using synthetic food scents to increase sales). Consumer Research Magazine, 18(10), 8–10.

Hutton, J. D., & Richardson, L. D. (1995). Healthscapes: The role of the facility and physical environment on consumer attitudes, satisfaction, quality assessments, and behaviors. Health Care Management Review, 20(2), 48–61.

Kim, W. G., & Moon, Y. J. (2009). Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 28(1), 144–156.

Kotler, P. (1973). Atmospherics as a marketing tool. Journal of Retailing, 49(4), 48–64.

Kryter, K. D. (1985). The effect of noise on man. Academic Press.

Lin, I. Y. (2004). Evaluating a servicescape: The effect of cognition and emotion. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 23(2), 163–178.

Lin, I. Y., & Mattila, A. S. (2010). Restaurant servicescape, service encounter, and perceived congruency on customers’ emotions and satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 19(8), 819–841.

Lucas, A. F. (2003). The determinants and effects of slot servicescape satisfaction in a Las Vegas Hotel Casino. UNLV Gaming Research and Review Journal, 7(1), 1–19.

McDonnell, A., & Hall, C. (2008). A framework for the evaluation of winery servicescapes: A New Zealand case. Pasos: Revista de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural, 6(2), 231–247.

Medabesh, A., & Upadhyaya, M. (2012). Servicescape and customer substantiation of star hotels in India’s metropolitan city of Delhi. Journal of Marketing and Communication, 8(2), 39–47.

Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). The basic emotional impact of environments. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 38(1), 283–301.

Morrin, M., & Ratneshwar, S. (2003). Does it make sense to use scents to enhance brand memory? Journal of Marketing Research, 40(1), 10–25.

Nguyen, N., & Leblanc, G. (2002). Contact personnel, physical environment and the perceived corporate image of intangible services by new clients. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 13(3/4), 242–262.

North, A. C., Hargreaves, D. J., & McKendrick, J. (1999). The influence of in-store music on wine selections. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(2), 271.

O’Neill, R. E. (1992, December). How consumers shop. Progressive Grocer, 71, 62–64.

Patterson, P. G., & Spreng, R. A. (1997). Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(5), 414–434.

Reimer, A., & Kuehn, R. (2005). The impact of servicescape on quality perception. European Journal of Marketing, 39(7/8), 785–808.

Ryu, K., & Han, H. (2010). Influence of physical environment on disconfirmation, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty for first-time and repeat customers in upscale restaurants. International CHRIE Conference-refereed Track, 13, 1–13.

Tom, G., Barnett, T., Lew, W., & Selmants, J. (1987). Cueing the customer: The role of salient cues in consumer perception. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 4(1), 23–28.

Tombs, A., & McColl-Kennedy, J. R. (2003). Social-servicescape conceptual model. Marketing Theory, 3(4), 447–475.

Turley, L. W., & Milliman, R. E. (2000). Atmospheric effects on shopping behaviour: A review of the experimental evidence. Journal of Business Research, 49(2), 193–211.

Vilnai-Yavetz, I., & Gilboa, S. (2010). The effect of servicescape cleanliness on customer reactions. Services Marketing Quarterly, 31(2), 213–234.

Wakefield, K. L., & Blodgett, J. G. (1996). The effect of the servicescape on customers’ behavioural intentions in leisure service settings. Journal of Services Marketing, 10(6), 45–61.

Yalch, R. F., & Spangenberg, E. (1988). An environmental psychological study of foreground and background music as retail atmospheric factors. In AMA educators’ conference proceedings (Vol. 54, pp. 106–110). American Marketing Association.

Yalch, R., & Spangenberg, E. (1990). Effects of store music on shopping behavior. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 7(2), 55–63.